But that emotion is destroyed by bad governance, says Siddharth Dube, author of a book that’s a personal history about being gay

Siddharth Dube

ADVERTISEMENT

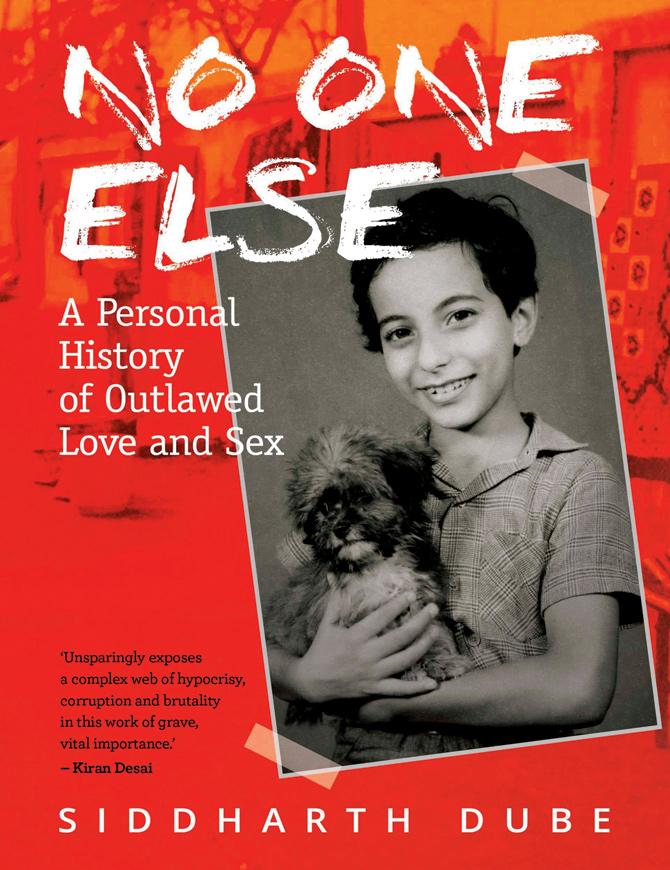

New York-based Siddharth Dube, 53, author and commentator on poverty, public health and development, released his third book, No One Else: A Personal History of Outlawed Love and Sex, published by HarperCollins, yesterday. Dube, whose book centers around the LGBT community and women sex workers in India, spoke to us about why he has mixed feelings about being gay in India.

Pic/MARGUERITE HEEB

Q. What is a personal history? Is this a different genre from a memoir or autobiography?

A. A personal history is not strictly a memoir, it is a more amorphous, broad in style, a history of myself intertwined with two social justice causes that I’ve cared passionately for 25 years. It’s about the matter of securing fundamental rights for gay people and for sex workers, both of whom are similarly criminalised in India and elsewhere. My personal life faded out in my mid-30s and took a backseat to my work, and the book is keeping with this.

Q. How honest have you been in the book?

A. It has taken all my courage and determination to write so honestly and candidly about myself, especially about my twin “burdens” of being a feminine boy and then being gay. The first chapter is titled Shame — perhaps that says it all, and expresses what it feels to look back at the life that began with the most crippling feelings of shame. This was in the 1960s, in anglicised Calcutta, a harsh Victorian setting. Anyhow, that particular burden just intensified during my years at Doon, which like most boys-only schools of the British public school mould, was an unedifying and brutal place, at least in that era. So yes, I’ve had to struggle with writing this, and portraying myself not as the successful, confident person I’ve become, but as that ashamed little boy.

Q. The contemporary audience may be getting weary of the oppressed gay narrative…

A. I’m honestly astonished to hear that there are reportedly people who say that they are getting tired of it. The overwhelming majority of gay women and men in India lead desperate, difficult lives — because of the colonial Section 377 — and because most do not belong to privileged urban backgrounds.

Q. Even though homosexuality is criminalised here, we have now started seeing more acceptance and realistic portrayals of the community in India...

A. I have conflicting feelings about India and being Indian. On the one hand, there is no other place that fills me with such great hope. Not only is there democratic empowerment, but many Indians remain characteristically accepting and gentle, not fired up with self-righteous moralising about others. But — and this is India’s continuing tragedy — all that potential is squandered by the bad governance of a breathtakingly corrupt political class. It is high time we held each one of them accountable.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!