Many Jewish Americans choose to write G-d instead of God. By not taking God's name directly, they show respect

Illustration/Devdutt Pattanaik

ADVERTISEMENT

Many Jewish Americans choose to write G-d instead of God. By not taking God's name directly, they show respect. Jewish people believe that long ago, maybe 4,000 years ago, G-d gave Moses the history of his people, and the law, which he recorded in five books which constitute Torah, the Jewish Bible. This written word of God, written in Hebrew, is read out in the Jewish synagogue regularly. Here, we find 613 commandments of God, equal to the number of seeds in a pomegranate, say some, which is why many believe that the Forbidden Fruit of the Jewish people was probably the pomegranate, and not the apple of the Christian Bible.

Many Jewish Americans choose to write G-d instead of God. By not taking God's name directly, they show respect. Jewish people believe that long ago, maybe 4,000 years ago, G-d gave Moses the history of his people, and the law, which he recorded in five books which constitute Torah, the Jewish Bible. This written word of God, written in Hebrew, is read out in the Jewish synagogue regularly. Here, we find 613 commandments of God, equal to the number of seeds in a pomegranate, say some, which is why many believe that the Forbidden Fruit of the Jewish people was probably the pomegranate, and not the apple of the Christian Bible.

Over the centuries, along with this written word of God, the Jewish people collected the orally transmitted laws of their people, and the various commentaries on it. This collection of laws in Hebrew that existed 2,000 years ago, and its commentaries in Aramaic over the last 2,000 years, along with references, and indices, constitute the Talmud.

The Talmud was compiled in Jerusalem first, and then in Babylon, after the Jewish people were forced into exile by Assyrians who destroyed their temple 2,500 years ago. Later, many returned during the rule of the Persians, only to be exiled again during the Greek and Roman occupation of Jerusalem 2,000 years ago. Over the centuries, exiled in many lands, Jewish scholars wrote commentaries on the laws of God, and there were commentaries on these commentaries. Everything was collected carefully, for they dealt with every aspect of Jewish life.

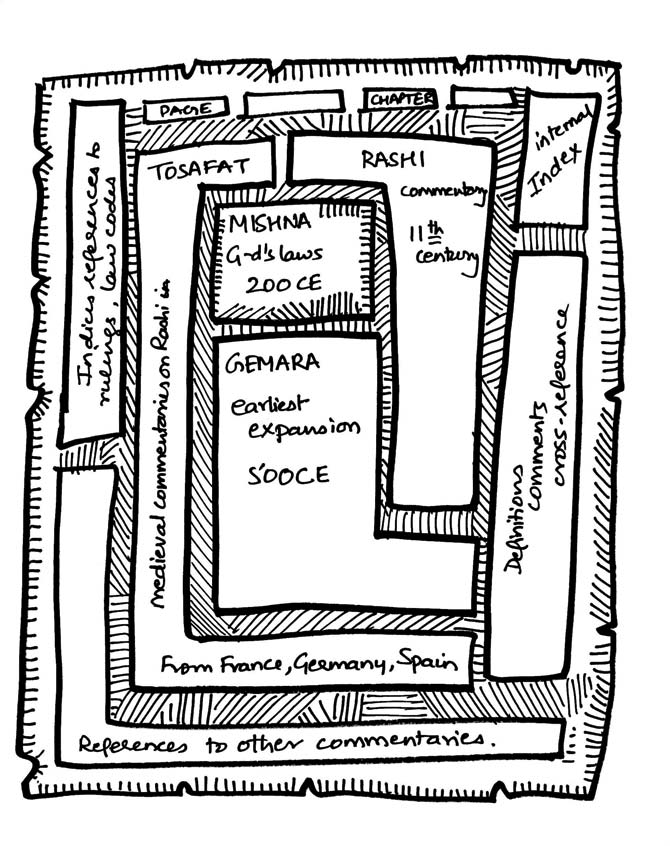

Talmud has six orders, each of which is divided into 63 sections. Currently, there are 517 chapters, over 10 million words and 6,000 pages in 38 volumes. And what is remarkable is that the Jewish people did what the rest of the world discovered only after the invention of the Internet: they developed a system of 'cross-referencing' and 'crowd sourcing' so that the reading is not mono-linear: word to sentence to paragraph to chapter, from page to page. The design is poly-linear: you can jump from one page to another via cross-referencing; and within a page you can witness the various commentaries and debates of scholars occurring over history across geographies.

The most amazing thing is the design of the Talmud page. It is designed almost like a series of concentric circles. In the centre is the Mishnah that captures the oral law prevalent in 200 AD. The earliest discussion on Mishnah, dated between 200 AD and 500 AD, is captured below it, as the Gemara. Around this on one side is the Rashi, notes by a 11th century French scholar that enable the reader make sense of the Mishnah and Gemara. On the other side is the Tosafot that comments on the Rashi. Then there are internal cross-references to other passages in the Talmud that deal with similar laws, as well as external cross-references to other books with other commentaries. In effect, one is able to see the views of various scholars of the Jewish diaspora separated over time and space in one single page.

Typically, the Talmud is read by two scholars, who in effect are discussing G-d's law with hundreds of scholars who lived before them in different parts of the world. As a result the hall where Talmud is being studied is a noisy interactive space, very different from the eerie silence of libraries where people read mono-linear books in isolation, cut off from people past and present.

The author writes and lectures on the relevance of mythology in modern times. Reach him at devdutt@devdutt.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!