Author-journalist and mid-day columnist Lindsay Pereira’s soon-to-release novel revisits an Indian epic and a time that redefined the social fabric of Mumbai

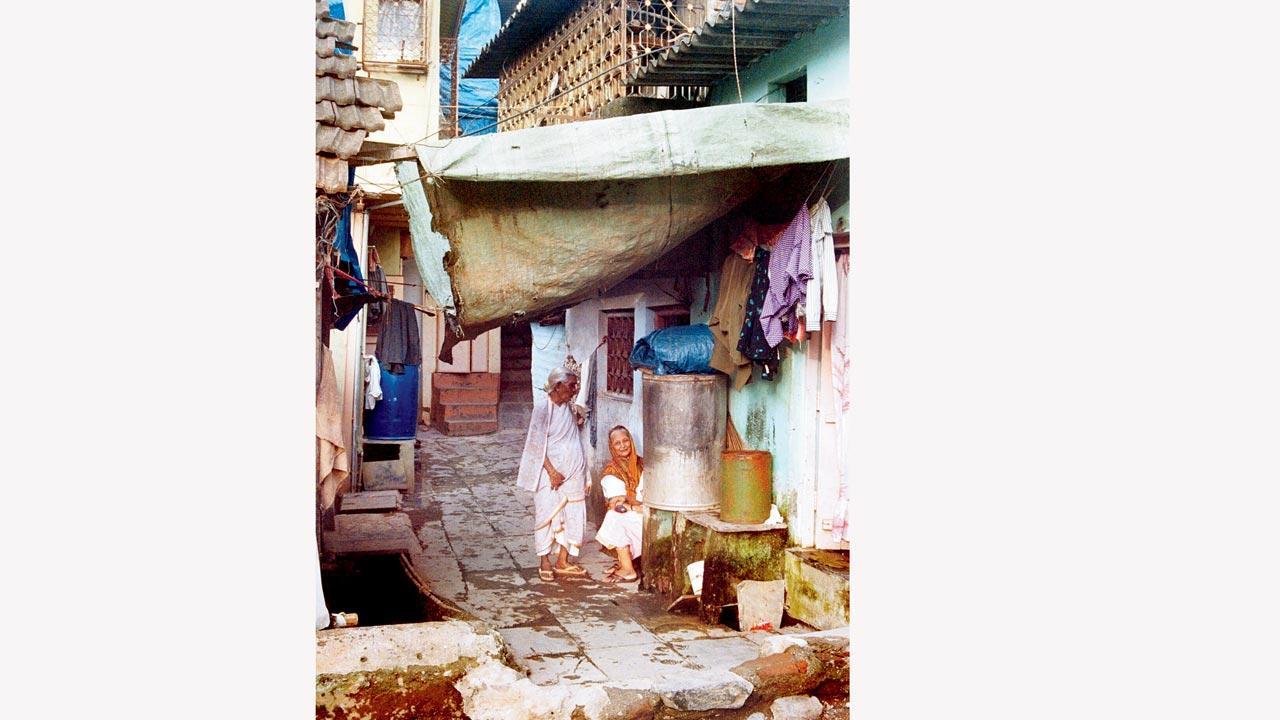

Radhabai Chawl in Jogeshwari East where six people were burnt to death in January 1993. This incident became one of the defining moments of the riots that many including Pereira say, changed Mumbai forever. mid-day file photo

Lindsay Pereira’s second novel has been in the making for nearly 15 years. “I kept thinking about it in some form or another. But, I would keep putting it off, because it was really easy for it to tip over into cliché,” he tells us over a call from the US. Where his first book, Gods and Ends, offered a telling portrait of a motley bunch of Catholic residents living in Orlem’s Obrigado Mansion, The Memoirs of Valmiki Rao (Penguin Random House), takes us into the decrepit chawl of Ganga Niwas in Parel, which becomes the canvas for his retelling of the Ramayana. “Everyone has their version of the epic, and everyone assumes they know it. So, I was quite wary. I started writing, and then abandoned it, and even asked myself, ‘Why I am doing this?’ But it got to a point, where I thought if I don’t do it, I would never be able to get it out of my system.”

ADVERTISEMENT

One thing was certain, though. Pereira wanted to tie his story to an event that he says was important to him: The Mumbai riots of 1992-93. “I still feel very strongly about it,” he says, “I draw a straight line from when it happened to the state of Mumbai today, and hold the riots responsible for the irreversible damage to the fabric of the city—the ghettoisation, the rise of bigotry and the insistence on people conforming to ideas that come from a certain set of politicians. What hurts me the most is that people who were responsible for it, have been absolved of all responsibility over time.”

Pic/Hemal Shroff

Pic/Hemal Shroff

Set in the peak of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement that led to the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya and the subsequent riots in Mumbai, Pereira’s novel is steered by Ganga Niwas’ old-time resident, the retired postmaster Valmiki Ratnakar Rao, who has been moonlighting as a diarist, secretly documenting the unbecoming of Rameshwar Shinde, whose life’s story is irrevocably linked with the gruesome events of the time. Rameshwar’s love interest Janaki and the local goon Ravinarayan Kumar are among the cast of characters in this modern-day retelling. That Pereira wanted to tell this story through the lens of an epic, is purely because of his own curiosity. “I have been thinking about myth and epic for years,” he shares. “Look at the epics in the East—the Iliad or Odyssey, for instance—and compare them with those from the East, Ramayana or the Mahabharata.” In the case of the latter, he says, the epics have impinged on our daily lives to such an extent that they spillover from the text into the real world, and have very serious repercussions. “I don’t see the voyage of Odyssey affecting the people of Greece today, or anything from the Iliad having an impact on the politics of the entire region where it emerged from. And yet, for us [Indians], these two epics not just affect our politics, but also our social fabric, and the way we think.” The Ramayana, he says, in particular, continues to be part of our collective consciousness. “But, there’s something very interesting about the Ramayana, which I believe has been lost when it comes to how we look at it today. It’s not just a story about exile; the notion of ‘Ram Rajya’ or ‘ideal state’ is also a very intrinsic part of it. The irony is that whenever we have pushed this idea, we have gone further and further away from what an ideal state should be.” That’s what the Ram Janmabhoomi movement did, he thinks. “The events and the myth had a direct impact on my city and me, and that’s why I had to take a personal approach.”

Retelling an epic, Pereira admits, is “incredibly daunting”. “There will always be someone who says that this book doesn’t do justice to what their idea of the Ramayana is,” he says, “But to be fair, I am not doing a faithful retelling. I am picking and choosing bits that would help my story.”

He chose to locate his story in a chawl for sociological reasons. “The chawls [of Mumbai] were like petri dishes... a microcosm of what was happening in the city at the larger level. These chawls also represented a group of people who were disenfranchised economically; this made it easier for any political party to take the residents, especially the younger lot, under their wings and train them to become these ‘warriors’. That’s how these areas became strongholds of certain parties,” says Pereira. There was also a logistical motivation. “From a narrative perspective, I had to also come up with this notion of ‘crossing over’ into Lanka. I had to find a realistic approach to do that, without it coming across as comical.. that was hard to do.”

Pereira’s narrator Valmiki is a broken man, and not without reason. “The disillusionment he feels is real; he is someone who is writing a story at a time that’s radically different from when the original epic came into being. What would happen if the same chronicler had to revisit those same events in our time?” he asks. “Nobody who respects the Ramayana, can look at how we have reinvented the story of Lord Rama, and not be disillusioned.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!