Meet the one-woman army who became the force behind some of Indian classical arts’ heavyweights who performed in Europe in the 1980s and ’90s

Shireen Isal. Pic/Bipin Kokate

In the Bombay Parsi home that London-based writer and former impresario Shireen Isal grew up in, it was Western music that prevailed. She was brought up on, and extensively studied, the piano. The Indian classical arts never really figured in conversations at home or even otherwise, she tells us, when we meet at the Royal Bombay Yacht Club on a weekday morning during her visit here. It comes as a surprise that Isal, in her later years, would go on to manage nearly 50 Indian classical artistes and their accompanists, spearheading almost 600 events in 16 European countries for them. She admits that nothing in her early years prepared her for it. But, her home city was where the groundwork for this began. While working at the Alliance Française de Bombay in the early 1970s, a chance encounter with Padma Shri, dance historian and critic Sunil Kothari, led her to discover other Indian classical arts. “For the next year-and-a-half or two, I went to every conceivable performance possible [in the city], and listened and watched, speaking to people in the field,” she recalls. By the time, she got married and moved to Paris, she realised that there’s “no other field I wanted to work in”.

ADVERTISEMENT

In her new book, Joy, Awe and Tears: My Association with Sargam, available on parsiana.com, Isal goes down memory lane to when she started her own artiste management organisation, Sargam, which became the nerve centre for several leading Indian classical artistes, who wanted a platform in Europe. While working briefly as cultural assistant at the Indian Embassy in the French capital, she got the opportunity to liaise with French organisers and artistes involved with Indian culture. “Once, the cultural councillor asked me, on a very short notice, to organise a performance for Swapnasundari [leading exponent of Kuchipudi and Bharatanatyam]. The show was a great success, and I remember, as we were returning to the hotel [where she was put up], I happened to tell her that I was planning on leaving [my job] as I was finding it very difficult to look after my baby. I asked her if she thought I could do this organisational work [on my own]. She said, ‘Not only will you be able to do this, I’ll also be the first artiste [you manage] next year’. She stuck to her word when I began in October 1979.” As an impresario, Isal says she represented Indian classical artistes—“I didn’t organise the events,” she clarifies. “I went through organisers [who wanted to do these shows, and call these artistes],” she says. It wasn’t a financially viable enterprise. “Artistes would give me 15 per cent of their earnings from their shows, which I ploughed back into my organisation, and that helped me cover my costs. It wasn’t easy, especially since I was doing this entirely on my own.”

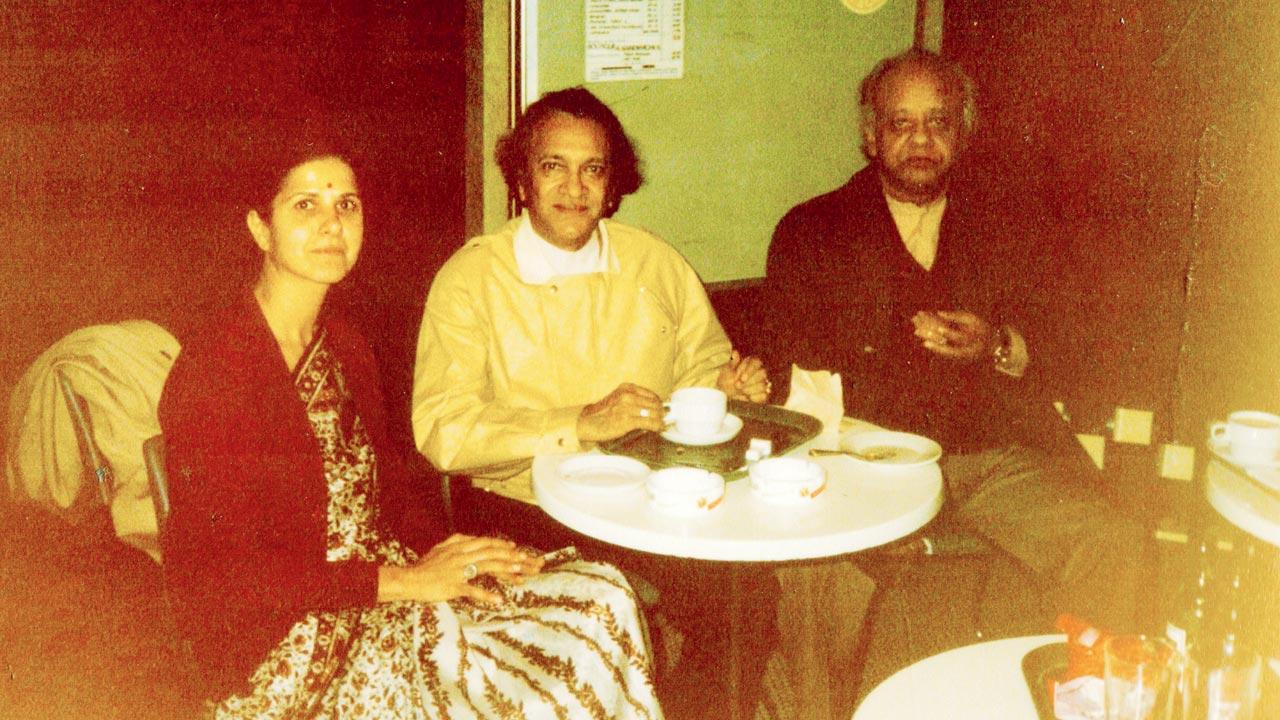

Isal with Pandit Ravi Shankar and Ustad Alla Rakha, in 1984. It was the late sitar maestro who gave her association its name

Until 1983, Isal worked on an ad-hoc basis. “I didn’t even have a structure. But when [Pandit] Raviji [Shankar] came on board, I suddenly felt we needed something more concrete. That’s when I registered as a non-profit. We still didn’t have a name. Then Raviji arrived in Paris. I remember being very nervous. So, my husband Jean-Pierre decided to drive Raviji to the hotel. During that drive, Jean-Pierre may have mentioned to him that we were looking for a name for our organisation, and that’s when he came up with the name, Association Sargam.” The logo was designed at Chimanlals Pvt Ltd in Fort.

Isal had a near nine-year association with Pandit Ravi Shankar helping him find concerts in Paris; she had an even longer professional relationship with his sister-in-law Lakshmi Shankar, who she says became family. The late Ustad Bismillah Khan, however, had a lasting impact on her. “Nobody came anywhere close. He was unique. Even now, I talk to him every day. He taught me so much. When I was going through a personal sorrow, Khansahib gave me advice that was easy to comprehend and comforting to live with. He also symbolised an immense, deep and unwavering faith in God, and that I think, coloured everything he said and did,” she shares. During the long drives to their concert halls or hotels, he’d never talk. “He was always praying, and sometimes, I’d find myself doing the same.” The last time they met—a few years before his passing in 2006—at the Nehru Centre in Mumbai, he told her, he’d come running, if she invited him. “That’s my only regret.” The shehnai maestro, she says, could never envisage a trip to the West without a mandatory pilgrimage to Karbala in Iraq. “But the war had broken out in Iraq, and the city was only accessible via an overland route from Jordan, and he was too old for that.” She also writes about many celebrated artistes, Begum Parveen Sultana, Geeta Radhakrishna and Bharatanatyam exponent Rohinton Cama whom she feels “has never received his just dues by way of performances and participation in dance recitals [in his home country],” which led to his tragic early retirement from the dance scene.

Ustad Bismillah Khan and Isal in 1993. Pics Courtesy/Association Sargam

Ustad Bismillah Khan and Isal in 1993. Pics Courtesy/Association Sargam

She has steered away from talking about the unpleasant events with artistes, even though there were a few because she feels it would breach their trust. On an average, Sargam sent every artiste to at least six different European cities. “Raviji really laid the groundwork for other Indian artistes. I think it’s very important that everyone realises his contribution.”

Isal ran Sargam for 39 years between Paris and London, where she moved with family in 1990; she hung her boots in 2018 with one last performance by her dear friend Begum Parveen Sultana. “Sargam wouldn’t have been possible without these artistes. They were all so gentle and understanding of the conditions in which I was working. I owe them a huge debt.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!