A new book unearths the work of a German cinematographer whose Expressionist sensibilities redefined how India experienced cinema and the mega stars on Bombay Talkies’ payroll

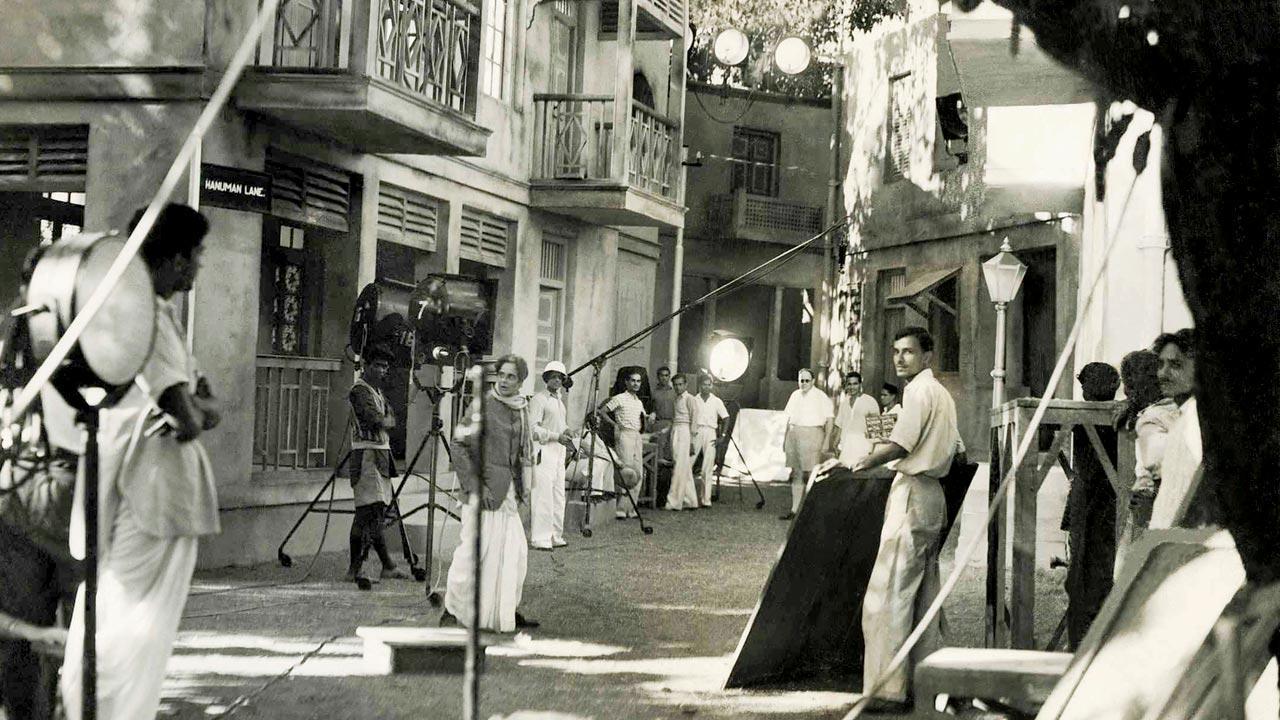

An elaborate lighting set-up for an outdoor scene shot on a built set for Bhabhi (d. Franz Osten, p. Bombay Talkies, 1938). Bombay Talkies’ popular comedian, VH Desai, can be seen rehearsing a scene in which he mistakenly flees from the good-natured protagonist, P Jairaj. Courtesy/Bombay Talkies: An Unseen History of Indian Cinema, edited by Debashree Mukherjee

The story of Josef Wirsching is intimately tied with the story of Bombay Talkies, a film studio that has an undisputed place in the history of Indian cinema. While films like Achhut Kanya (1936) and Kismet (1943) are considered important milestones in the career of sound cinema from Bombay (now Mumbai), many of the studio’s stars and technicians actively shaped commercial filmmaking in twentieth-century India. From Ashok Kumar, who started as a rookie laboratory assistant at the studio, to Dev Anand, who made his acting debut with Ziddi (1948), several of India’s best-loved stars began their film careers at Bombay Talkies. Interestingly, a review of Ziddi in the Times of India noted that the film was “distinguished by some of the finest photography we have seen in years on the Indian screen—the camera in fact steals the picture,” and therefore, according to the reviewer, the real star of the film was not a debutant Dev Anand but Josef Wirsching’s cinematography.

ADVERTISEMENT

Kishore Sahu, Josef Wirsching and Kamal Amrohi gather around Meena Kumari during the shooting of Dil Apna Aur Preet Parai (d. Kishore Sahu, p. Kamal Pitures, 1960)

Kishore Sahu, Josef Wirsching and Kamal Amrohi gather around Meena Kumari during the shooting of Dil Apna Aur Preet Parai (d. Kishore Sahu, p. Kamal Pitures, 1960)

The work of reinstituting Josef Wirsching within the known history of Indian cinema offers us an expansive perspective on the contours of so-called national cinemas. How can a German cinematographer be considered a pioneer of Indian cinema? And what was he doing in the Bombay film industry in the first place? Tracking these questions leads us to a fascinating network of people, places, and practices that converged on Bombay city in the 1930s. From London to Lahore, Calcutta (now Kolkata) to Berlin, the Bombay film industry was built by people and resources from across the world. When one enquires after the ethnicities, linguistic identities and nationalities of the pioneers of Bombay Talkies, it becomes clear that the category “Indian cinema” is a tenuous construct and includes a wide array of trans-regional and transnational influences, borrowing from Hollywood and Parsi theatre, even as its practitioners crossed the borders of old and new nation states.

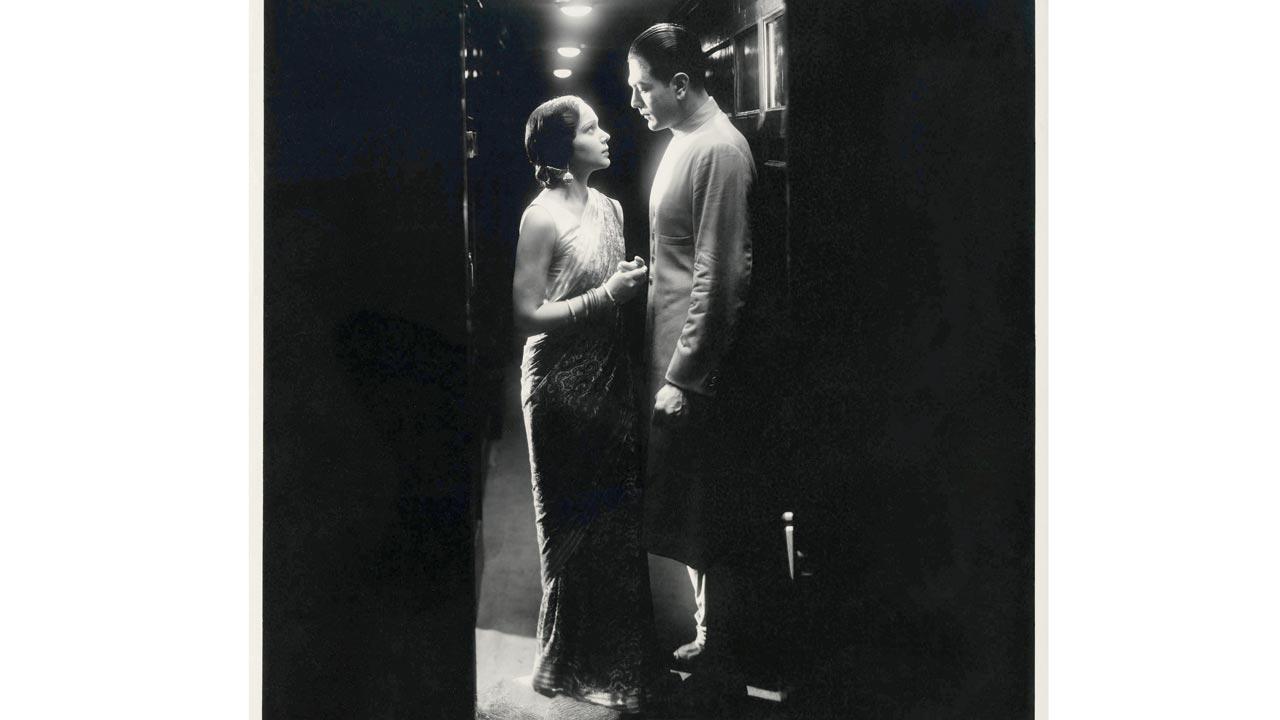

Kamala (Devika Rani) and Ratanlal (Najmul Hussain) share an anxious moment on board a speeding train in Bombay Talkies’ debut feature film, Jawani ki Hawa (d. Franz Osten, 1935). The recently-released web series Jubilee by Vikramditya Motwane is loosely-based on the legendary film studio founded by Himansu Rai and Devika Rani, and her scandalous love affair with Hussain

Kamala (Devika Rani) and Ratanlal (Najmul Hussain) share an anxious moment on board a speeding train in Bombay Talkies’ debut feature film, Jawani ki Hawa (d. Franz Osten, 1935). The recently-released web series Jubilee by Vikramditya Motwane is loosely-based on the legendary film studio founded by Himansu Rai and Devika Rani, and her scandalous love affair with Hussain

Josef Wirsching’s decision to move to Bombay in the 1930s seems mainly motivated by the fact that film studios in Germany were being taken over by the Nazi Party and non-Jewish filmmakers were being compelled to make propaganda films. This coercive atmosphere made artistic production very difficult for many independent-thinking filmmakers. Wirsching was very young when he shot Light of Asia with Franz Osten and Himansu Rai and still only 31 years old when he chose to join Bombay Talkies. Newly married, the world was wide open for both Josef and Charlotte Wirsching, even as Germany felt constricting. Unlike many others who made the eastward journey to India during the Nazi years, Wirsching was neither Jewish nor a political exile. Still, his decision to migrate to and make a career and home in India is significant.

Bombay Talkies offered Wirsching the professional status and creative freedom that was not possible in Germany’s crowded and politicised film scene. Moreover, the content and themes of Bombay Talkies’ films, with their emphasis on progressive reform and the socially marginalised, offered a worthy vision of an inclusive future that was the antithesis of the Nazi project.

Helen rehearses the cabaret number, ‘Yeh itni badi mehfil aur ik dil, kisko doon,’ for the film Dil Apna Aur Preet Parai (d. Kishore Sahu, p. Kamal Pictures, 1960). Wirsching and his wife, Charlotte make an appearance in the song as guests at the party

Helen rehearses the cabaret number, ‘Yeh itni badi mehfil aur ik dil, kisko doon,’ for the film Dil Apna Aur Preet Parai (d. Kishore Sahu, p. Kamal Pictures, 1960). Wirsching and his wife, Charlotte make an appearance in the song as guests at the party

Bombay cinema from the 1930s to the 1950s reveals a strong influence of German Expressionism and Josef Wirsching played a pioneering role in popularising this stylised film form. The Expressionist vocabulary is strongly imprinted in Wirsching’s lighting designs and compositions. German Expressionism, in the cinema of the 1920s (e.g. The Cabinet of Dr Caligari), was a strongly non-naturalistic style that used mise-en-scène to exteriorize inner emotions. Sets, costumes, acting and lighting all took on the role of “expressing” complex and dark human psychology.

Wirsching was a versatile and highly adaptive artist, who moulded his cinematic craft to suit the script and the studio’s vision. His cinematic eye for drama allowed him to skillfully switch registers between Expressionism, naturalism and realism. As Bombay Talkies tried to distinguish itself from its local competitors and craft its own aesthetic style, Wirsching experimented with different lighting styles and budget contingencies, using low-key, single-source lighting for emotionally heavy or suspenseful scenes alongside high-key, evenly lit designs. Wirsching’s work is memorable for his luminous framing of heroines, crafting glamorous images for some of India’s most beloved actresses. Wirsching also proved adept at outdoor location shooting and made full use of the studio’s Bombay location to film the natural landscape of the Western Ghats. His use of Expressionist techniques returned in full force in Mahal (1949), a Gothic thriller. Wirsching’s partnership with Kamal Amrohi through the 1950s and 1960s marked the zenith of his artistic career, with two stunning black-and-white features, Mahal and Dil Apna aur Preet Parai (1960), and his first and final colour film, Pakeezah (1972).

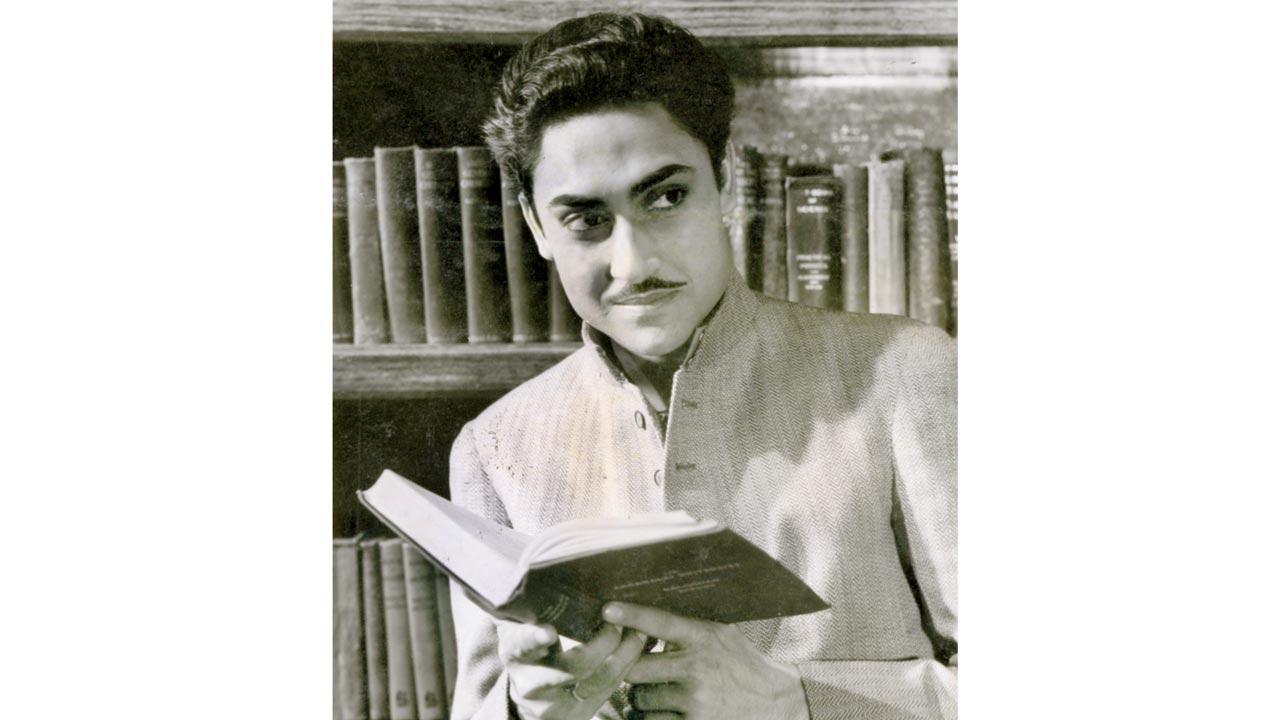

Ashok Kumar in a publicity still for Nirmala (d. Franz Osten, p. Bombay Talkies, 1938)

Ashok Kumar in a publicity still for Nirmala (d. Franz Osten, p. Bombay Talkies, 1938)

The cosmopolitan crew at Bombay Talkies—from Munich, Berlin, London, Calcutta, Allahabad, Bombay, Lucknow, Lahore and several other towns and cities—brought together influences from German Expressionist theatre and cinema, Bengal school portraiture, Orientalist adaptations of Sanskrit literature, British socialist plays, modern Bengali reformist novels, Art Deco industrial design, Bauhaus textile design, Hindustani classical music and kathak dance conventions. Bombay Talkies played a foundational role in defining India’s commercial film form, producing some of the most iconic musical films of the era which foregrounded urgent issues of social reform. These films borrowed freely from East and West to create a heady pastiche that once again begs us to question easy notions of Indian and foreign, traditional and experimental.

Excerpted with permission from Introduction: What Photography Can Tell Us About Cinema’s Past by Debashree Mukherjee in Bombay Talkies: An Unseen History of Indian Cinema, edited by Debashree Mukherjee, published by Mapin Publishing, in association with the Alkazi Collection

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!