A third-generation restaurateur reconnects with the land of his Partition-refugee grandfather, with an intimate fine-dining space inspired by undivided Punjab’s famous river

Taftan, which is a lot like the Indian naan, but slightly sweeter and is kneaded with saffron water, is best enjoyed with murgh makhani or Kashmiri rogan gosht

On the map, the Jhelum is a blue line that meanders and flows in a trajectory splintered by the Partition. Rising from a deep spring at Vernag, in the western Jammu and Kashmir union territory in India-administered Kashmir, it races through the Kashmir valley to Wular Lake in Srinagar, where it calms and stills, before bending southwards into the Pakistani province of Punjab. Before 1947, Jhelum resided in one land, now it departs into another.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Chhabras, like the river, were oblivious of their future—they were affluent landlords, living in Gujranwala in undivided Punjab, through which the Jhelum flows. A recklessly drawn border forced the family out of their hometown. Joining the sea of refugees, Raj Kumar Chhabra arrived in Bombay with his parents and two siblings on a train, moving into a camp in Chembur.

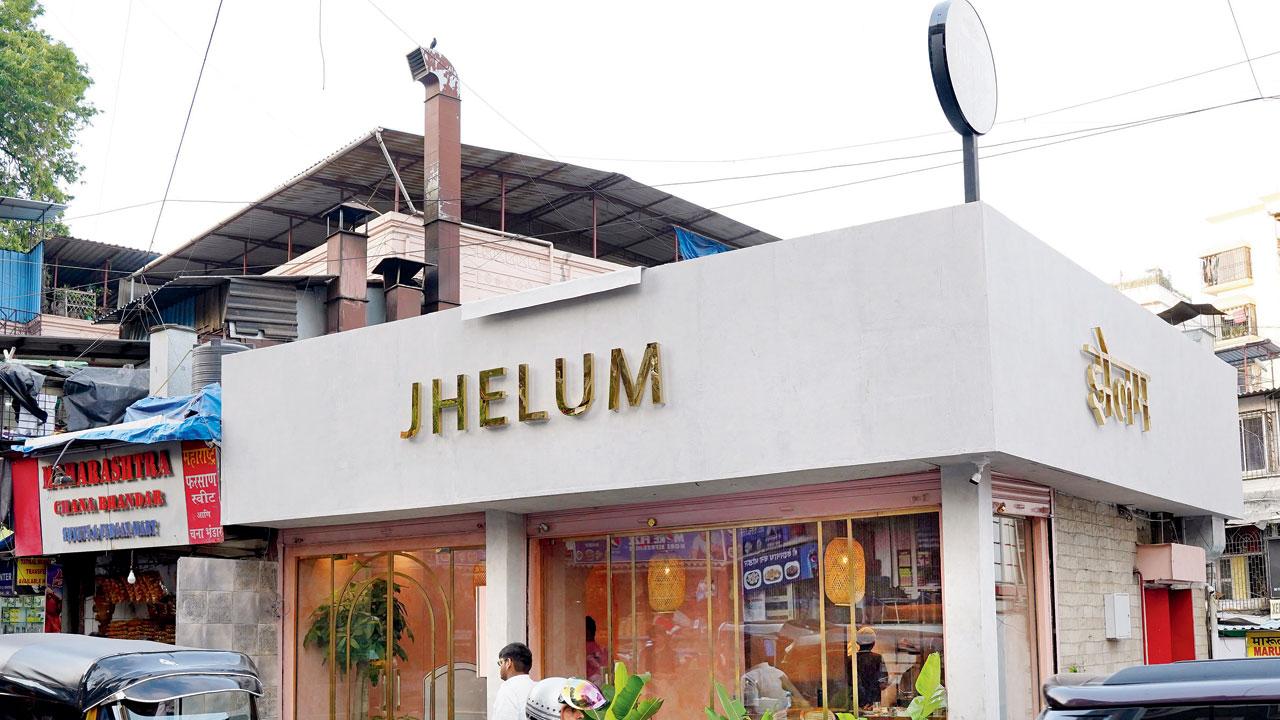

Abhay Chhabra’s just launched Jhelum restaurant in Pali Naka serves food made along the Jhelum river, which flows from Kashmir to Pakistan

From a life of affluence, they were reduced, almost suddenly, to a state of penury. Even as the Chhabras struggled to find their footing in this bedlam, their lives took an unexpected course—much as the Jhelum under the spell of torrential rain—when Raj Kumar’s father took ill. A hospital admission cost Rs 200, and it was back then, beyond affordable. Denied treatment, the patriarch passed on. “That was a turning point in my grandfather’s [Raj Kumar] life,” says 24-year-old restaurateur Abhay Chhabra.

Determined to save his family from another tragedy, Raj Kumar started a canteen business in Ravi Industrial Estate in Thane, serving North Indian food. The success of that eatery led him to open another one in Masjid Bunder six months later. He went on to launch New Neelam Restaurant and Bar; his son, Ajay Chhabra, expanded the chain that became a popular watering hole, which also served delicious Mughlai and Chinese food. The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree, we learn, when we meet Abhay, who is a third-generation Chhabra in the business of food.

His newly-launched restaurant in Bandra’s Pali Naka celebrates his roots, the land of his ancestors, and the river, a reminder of the ebb and flow of life. “I picked up dishes [eaten] along the banks of the river,” says Abhay of the menu, which is inspired from northwestern Punjabi and Peshawari, and Kashmiri cuisine.

Abhay ran his own event company, before moving into the tech startup space where he, along with two others, launched an app to help people with nightlife bookings. In 2019, the year before the pandemic, he opened the fine-dining restaurant and lounge B52 at Khar Gymkhana, which operates out of a 6,000 sqft space.

Jhelum is more intimate, with interiors reminiscent of the world they left behind. The pink on the wall represents the mud of the riverbanks, the blue lines on the fabric of the seat hark back to the river itself, and the beige and brown, the colour of the earth. Cane lanterns give a dim glow to the tiny 30-seater, while quaint knick-knacks placed inside niches, imagine a forgotten past. But otherwise, this is still a chic modern space with a glass facade, drawing very much from a 20-something’s sensibility of how he’d imagine a cosy, fine dining space, where he can take his family and partner for a meal.

Dahi ke kabaab

The menu is slim. There are about 40 dishes, give or take, including rice and breads. This may help make a more focused choice, but the list appears sparse to us, perhaps because there are no descriptions of the dishes, a standard protocol at most restaurants. While Indians are familiar with pindi chole, murg malai kababs and the like, for someone who has never tried North Indian food, names without any instant recall value are nothing but random dishes. The waiting staff has been prepped for this shortcoming. “We took about six weeks to decide on the menu,” says Abhay. His brother in the US, a chef by profession, became his sounding board when planning and curating the meals. The chef, Yawer Hussain Faridi, has previously worked at New Neelam, and trained under the celebrated chef and Awadhi cuisine genius, Ishtiaq Qureshi.

The choice of location for his new experiment is interesting and even bold. Pali Naka is inundated with restaurants and eateries. Some, like Jai Hind Lunch Home bang opposite Abhay’s own space, have endured despite stiff competition due to patronage from fans old and new. To make friends in this crowd is going to be an uphill battle.

Dal Peshawari is cooked for over 72 hours, on slow heat over a tandoor. PicsAishwarya Deodhar

Dal Peshawari is cooked for over 72 hours, on slow heat over a tandoor. PicsAishwarya Deodhar

There isn’t a dearth of restaurants that serve Punjab and Kashmir on a plate. What makes this different? The dry ingredients and masalas, including the chole, Abhay says, are sourced directly from these regions, including Kashmir and Punjab, so that the restaurant remains authentic to the food of the land.

We try bits from the starters laid out for us—dahi ke kabab (Rs 385), chatpate tandoori aloo (Rs 350), murg malai kabab (Rs 475) and barrah kabab (Rs 595). The barrah kabab (Rs 595)—lamb chops marinaded in brown spices and skewered on a tandoor—served with green chutney, is soft and succulent. Lamb, if not cooked well, can be chewy. We enjoy it with our hands—messy but delicious. On the main course, there is the exceptional-tasting dal Peshawari (Rs 395), which we prefer having without the rice because it is so filling. “It is cooked for over 72 hours on slow heat over a tandoor in dum style, to get the right flavour and texture,” explains Abhay.

Having spent a significant part of his childhood at the New Neelam chains, Abhay also wanted to bring part of that legacy into the dining experience. The sweet and spicy murgh makhani (Rs 485) has been inspired by the butter chicken served there. “It’s the typical Neelam butter chicken,” he says, “The paya soup at Neelam was such a big hit that we would sell at least a hundred orders daily during winter. Because of its popularity, I decided to include paya masala (Rs 595) on our menu. It’s a gravy dish cooked with daal.”

Barrah kabab

One of our favourite dishes from the dinner was the Kashmiri rogan gosht with taftan, which is a lot like the Indian naan, but slightly sweeter and kneaded with saffron water. We’ve never tried this combination before, and that’s what adds an element of newness to this experiment.

We finish our meal with a dessert called mithi yaadein (sweet memories) (Rs 355), which is deseeded lychees drowned in a bowl of rabri, and garnished with nuts. It is mouth-watering, but by this time, we’ve eaten so much, it’s only gluttony that’s seeing us through. The other two sweet treats on the menu are malpua and phirni. “I want Jhelum to become a brand in itself, and that’s my dream. I plan to open more such outlets in India and abroad... perhaps London and NYC,” he says. Where the river can’t flow, he will.

Address: Jhelum, Pali Naka, Bandra

Timings: 12 Noon to 3.30 PM and 7.30 PM to 3.30 AM

Call: 8591438301

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!