Parents are finally realising the pandemic’s effect on children with rising cases of obesity, diabetes and vitamin deficiency. It could be the beginning of a viscous cycle of depression and body dysmorphia, fear doctors

Kirti Tawde encourages her daughter Ahilya, 5, to cycle. Last year, she suffered leg pain that made her limp. She was later diagnosed with Vitamin D3 deficiency due to no time outdoors. Pic/Sameer Markande

Putting on 18 kilos in under three years and fighting three major infections, including a bout of COVID-19, can take a toll on any child. It admittedly had the parents of a 12-year-old Mumbai kid, worried sick. The boy had been recovering from a more life-threatening respiratory pneumonia condition, when the pandemic hit in March 2020. “When he first fell ill in September 2019, he was on the ventilator, but with the help of our doctor and the staff at the [NH SRCC Children’s] hospital, he slowly recovered. To aid his recovery, he had been put on steroids, but we were told that the side-effects, if any, would resolve once he followed a more active lifestyle,” his father, requesting anonymity, tells mid-day.

ADVERTISEMENT

The boy had just started feeling better, when the first lockdown was announced. “Schools were shut indefinitely, and all his outdoor activities, including swimming, had stopped. He couldn’t go out and play with his friends in the building due to the strict quarantine rules. At the time, we noticed him suddenly put on a lot of weight,” his father remembers. The boy’s mother adds, “Since we are a Gujarati family, we enjoy a sweet treat with every meal. His paediatrician had warned that the medicines would cause weight gain, but we didn’t expect it to be so drastic.” By the end of 2020, their son had gained 10 kilos, and this was also affecting his self-confidence. The following year, he picked up COVID and later, typhoid, which again required hospitalisation. There was really no room for him to get back to rigorous physical activity.

Author Richa S Mukherjee’s daughter Anika, 8, has started exercising for the last three weeks. Anika had developed a paunch during the pandemic. Instead of making her conscious, her mum sat her down and gently explained the consequences of not taking care of her physical self. Pics/Sameer Markande

Author Richa S Mukherjee’s daughter Anika, 8, has started exercising for the last three weeks. Anika had developed a paunch during the pandemic. Instead of making her conscious, her mum sat her down and gently explained the consequences of not taking care of her physical self. Pics/Sameer Markande

Their son now suffers from childhood obesity, a condition that experts say exacerbated in the pandemic due to the multiple lockdowns and prolonged periods of social isolation. In 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated that there were nearly 39 million children under five years of age who were either overweight or obese. In the UK last year, the National Child Measurement Programme noticed the largest single-year increase in childhood obesity since the programme began 15 years ago. In India, health experts say that we are likely to be in the throes of a more worrisome epidemic of unhealthy, obese children. As of 2017, India had the second-highest number of obese kids (14.4 million) in the world, next only to China. The numbers could be much worse now, fears Dr Amish Vora, senior consultant, critical care and emergency specialist, Paediatric Intensive Care, at Masina Hospital in Byculla. Vora says he has seen a 20 to 25 per cent increase in obesity patients during the pandemic. It’s not obesity alone that’s affecting children who’ve survived two tumultuous years of the pandemic. Lack of good sleep, no exposure to sunlight, a sedentary lifestyle, excessive screen-time and eating junk has put kids at risk of several other physical ailments, including the more debilitating diabetes.

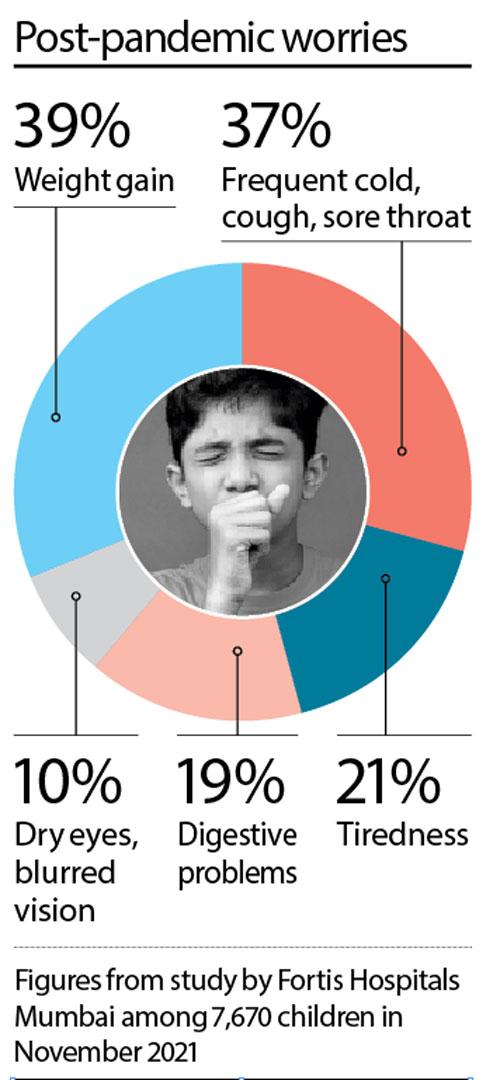

A study conducted by Fortis Hospitals Mumbai with 7,670 parents in November 2021, had highlighted that while children were largely spared from the direct health effects of COVID-19 with most of them displaying a milder infection, the crisis has had a profound effect on their physical wellbeing. About 37 per cent parents had stated that their kids suffered from frequent cold, cough and sore throat; 21 per cent said their kids were tired; 19 per cent spoke about digestive issues, and 10 per cent parents said their kids suffered from eye dryness, blurring of vision and had begun to need spectacles. Around 39 per cent parents said that their children had gained significant weight during the pandemic.

Andheri-based homemaker Kirti Tawde says her five-year-old daughter Ahilya complains of getting tired, when cycling or playing sports. Ahilya’s doctor has insisted she spend more time outdoors, as she was diagnosed with Vitamin D3 deficiency during the lockdown

Andheri-based homemaker Kirti Tawde says her five-year-old daughter Ahilya complains of getting tired, when cycling or playing sports. Ahilya’s doctor has insisted she spend more time outdoors, as she was diagnosed with Vitamin D3 deficiency during the lockdown

Homemaker and Andheri resident Kirti Tawde, who is mother to five-year-old Ahilya, says that her own anxieties and fears about contracting the Coronavirus, kept her from taking her daughter outdoors during the lockdowns, even when allowed. Ahilya doesn’t enjoy physical activity anymore. “It’s difficult to get her to try any outdoor or field sports. She is always complaining of being tired. She hesitates to even cycle downstairs. When I enrolled her for a skating class in the building compound, she wasn’t interested. She’d rather chit-chat with the other kids or play with them. I think she is trying to compensate for the lack of social interaction over the last two years,” says Tawde, adding that she is trying every rule in the book to build her daughter’s stamina. Tawde wants to avoid a repeat of the situation from last year, when Ahilya started complaining of severe leg pain. “She would even limp. I found that very strange because she was at home all day, and not exerting. But, she’d insist that I press her legs daily.” When Tawde took her to the orthopaedic she learnt that her daughter was Vitamin D3 deficient, which was causing muscle pain in her joints. “Though she was put on a month-long course, the doctor insisted that she get daily sunlight and also do a lot of physical activity to absorb the Vitamin D3 she was consuming orally,” says Tawde.

Goregaon-based Jayshri Chauhan’s 12-year-old daughter Mehak started physical school a month ago. During the lockdown, Mehak didn’t eat junk, as her diet was being strictly monitored by her mum. Despite that, the isolation took its toll. “It’s been weeks since physical classes began, and she still refuses to do anything else after returning home. She wants to sleep or spend time on the screen, which has led to puffiness under the eyes. While I would like her to participate in other extra-curricular activities, I think it’s best she takes her time to adjust to the new routine,” says Chauhan, who works as senior manager with a print management firm.

Jayshri Chauhan’s 12-year-old daughter Mehak doesn’t enjoy doing extra-curricular activities after school, as much as she did earlier. She wants to sleep or spend time on the screen, which has led to appearance of puffiness under the eyes, says Chauhan

Jayshri Chauhan’s 12-year-old daughter Mehak doesn’t enjoy doing extra-curricular activities after school, as much as she did earlier. She wants to sleep or spend time on the screen, which has led to appearance of puffiness under the eyes, says Chauhan

According to Vora, a lot of children consulting him have been experiencing breathlessness and fatigue, when involved in simple physical activity. “We saw several such cases right after the first wave. It indicates that the body’s mechanics to withstand mild exertion has gone haywire. We usually need to monitor the heart and lung function.”

When the pandemic brought life to a halt in March 2020, author Richa S Mukherjee remembers making a conscious effort to get her eight-year-old daughter Anika to work out along with her, at home. “I think the disenchantment happened at the end of the first year, after which I saw an absolute detachment with anything she was doing. It had hit her mentally, and then it manifested in her being churlish, which was unusual, because she is otherwise very well-behaved,” Mukherjee says. At some point, she stopped exercising, didn’t like her kathak and tabla classes. Her screen time increased as well, and she slowly started putting on weight. “When my father visited us recently, he casually commented about her paunch. She has always been a petite child, so a ‘pandemic pot-belly’ like this one would obviously show.”

Heer Kothari; Dr Sweta Budyal and Dr Amish Vora, Paediatric Intensive Care, Masina Hospital. (Pic/Shadab Khan)

Heer Kothari; Dr Sweta Budyal and Dr Amish Vora, Paediatric Intensive Care, Masina Hospital. (Pic/Shadab Khan)

Instead of making her conscious about the change, Mukherjee says she sat her daughter down and gently explained to her the physical consequences of her actions. It’s been three weeks since Anika has returned to exercising. To make it more fun, Mukherjee has given her daughter the liberty to choose a new activity she wants to try every day—yoga, meditation, jumping, dancing—over and above playing with friends in the building. “Of course, there are days when she doesn’t do any of this, but, I know that it’s at least on her agenda now.”

Entrepreneur, writer and educator Heer Kothari, who is a speech and drama teacher, says that many of her students who put on weight in the last two years, are experiencing low self-esteem and tend to be withdrawn. In a class like hers, where children are encouraged to express themselves through performance, this is proving to be an impediment. “Recently, when one of the boys in my class teased another kid for being fat, I decided to give them an improvisation topic, body-shaming. During the break out room, some of them shared that they do not like keeping their cameras on during virtual class, because they fear they will be mocked.”

According to Vora, most Indian parents are blind to obesity. “They are happy when they see their child eat well and put on weight,” he says, adding that this assumption that an obese child is “healthy” is not just misplaced, but can be dangerous. “Many parents come to us, not because their child is overweight, but because they have noticed deranged sugar [levels], increased heartbeat, breathlessness, sleeplessness or mood swings—these are all metabolic syndromes of obesity. They don’t realise that this is a vicious cycle. If you don’t sleep enough, you can get obese, and once you are obese, you are prone to depression. The problems will multiply.” Vora suggests that parents diligently check their child’s Body Mass Index—there are BMI calculators available online that require you to feed in weight and health data—to know whether they are in the safe zone.

A major fallout of the pandemic is Type 2 diabetes, a lifelong chronic condition, where a high-level of sugar (glucose) is seen in the blood. It usually develops over time, especially among those who are overweight or obese. Increased fat makes it harder for the body to use insulin the correct way. Vora says that with childhood obesity kicking in during the lockdowns, we are likely to see more cases of Type 2 diabetes in children over the next three to five years.

Dr Sweta Budyal, senior consultant endocrinologist and diabetologist, Fortis Hospital, Mulund, is already seeing a spike in cases. “In the early stages, we can reverse diabetes. But it can relapse, if the patient doesn’t follow a healthy lifestyle.” Her youngest patient is a nine-and-a-half-year-old obese boy. “He also suffered from a severe form of COVID infection, multisystem inflammatory syndrome, which caused frequent urination, excessive thirst and genital yeast infection. He was treated with steroids during the time.” But prior to this treatment, his fasting sugar was 265 and post-meal sugar was 330. When they did a Haemoglobin A1C test, the average blood glucose (sugar) levels for the last two to three months was 7.5, indicating that he had pre-existing diabetes. His diagnosis was done based on his increased body mass index, she shares. “Fatty liver and cholesterol are also now becoming a common problem among kids.”

The possible long-term effects of diabetes include damage to blood vessels, which can lead to heart attack, stroke, and problems with the kidney, eyes, gums, feet and nerves.

A recent study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, showed that children under 18 years, recovering from COVID-19, were also more prone to both Type 1 (a chronic condition in which the pancreas produces little or no insulin) and Type 2 diabetes. Vora says, “We are also seeing a rise in Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) [a more serious complication of diabetes that can be life-threatening]. Whenever there is a viral illness, your underlying diabetes gets exposed. This is not necessarily due to obesity. When I was [working] in the UK, and there was a swine flu outbreak, we noted a rise in DKA cases. Right now, we need more evidenced-based study to prove Coronavirus’s direct impact on the pancreas.”

Irrespective, Budyal and Vora feel that parents are underestimating the gravity of the indirect impact of the pandemic among kids. One of the biggest mistakes they make is not following up with the doctor, says Budyal. “They come for one or two consultations, and stop. Conditions like diabetes and obesity require long-term treatment, and the entire family needs to make a change for it to work.”

39 per cent

Percentage of parents from 7,670 surveyed by Fortis Hospital, Mumbai, who said their kids had gained weight in lockdown

39mn

No. of children globally under five years who are either overweight or obese in 2020, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates

What can parents do?

. Ensure your child gets uninterrupted sleep of at least eight-nine hours daily

. Avoid junk and sugar intake. Eat a balanced diet. Make sure that fruits and vegetables are part of the family’s daily food consumption

. Check their BMI annually

. Daily exercise of at least two hours is a must. Include activities like cycling, skipping, swimming and free play

. Screen time for those aged two and five should not exceed one hour

. Encourage social interaction; it is needed for healthy brain development

. Don’t ignore sudden weight gain or weight loss, frequent urination, dehydration

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!