An Uttar Pradesh native working in Bhayander was on death row for the rape and murder of a six-year-old. This month, 13 years later, he walked out a free man. Prakash Nishad talks about living a miracle

Prakash Nishad outside the Yerawada Central Jail in Pune, minutes after his release on May 21. Pic Courtesy/Project 39A

Prakash Nishad is 38. The last time he was at his Siddharth Nagar home with family, he was 25. He doesn’t have a job and is not quite sure how he is going to make ends meet. Yet, the most powerful emotion he feels, he tells mid-day over a telephone call, is gratitude. “Naya jeevan mil gaya hai [I have found new life],” he says. As clichéd as that line may be, nothing else comes close to summarising his circumstance. On May 19 this year, after 13 years of incarceration and eight years of waiting to be hanged, Nishad was cleared of all charges by the Supreme Court of India. And just like that, he was free.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nishad was at work—he was helper in a steel products factory—when a team from the Thane Rural Police’s Local Crime Branch whisked him away on June 13, 2010. He was accused of the rape and murder of a six-year-old girl.

The minor stayed with her parents in Bhayander and had gone missing while playing outside her home the previous day. Hours later, her body was found in an uncovered drain. A post mortem examination confirmed sexual assault before murder. The Bhayander police registered an FIR. The LCB was instructed to conduct parallel inquiries due to the serious and sensitive nature of the crime.

“I didn’t even know the girl,” Nishad recalls, admitting, though that he lived in the same chawl as the family.

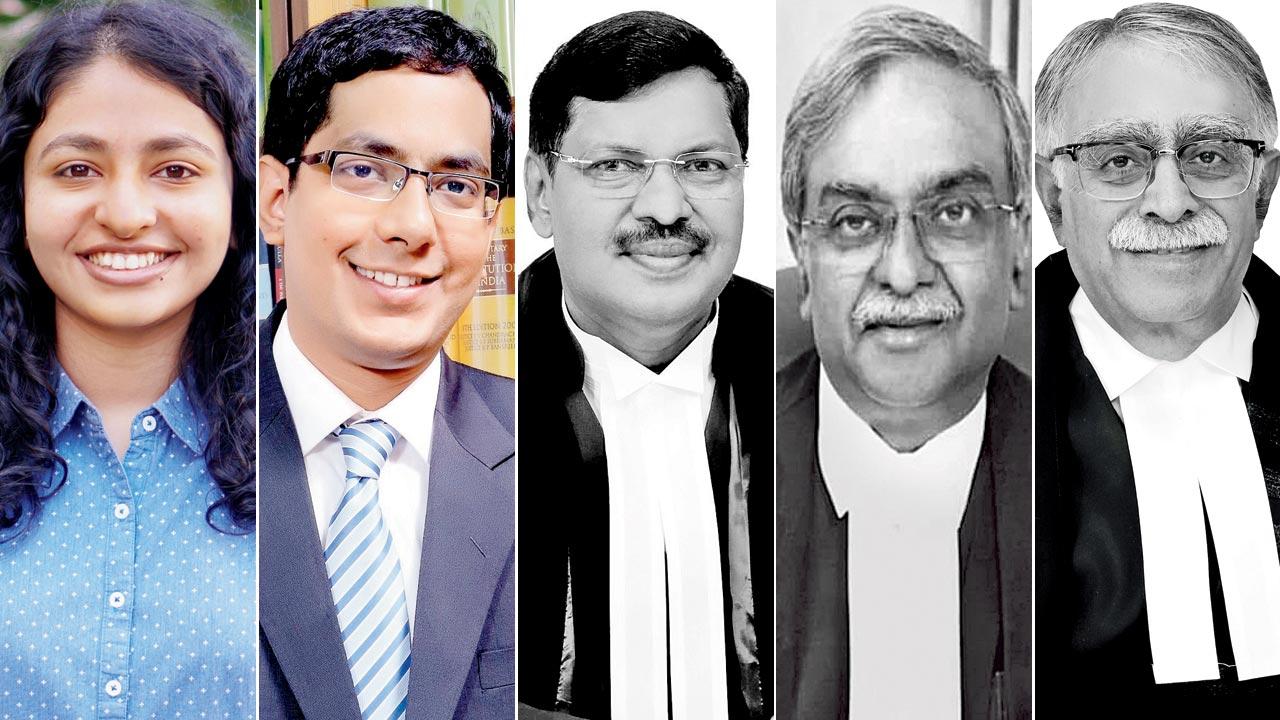

Adv Pratiksha Basarkar, Adv Rishad Ahmed Chowdhury, Justice B R Gavai, Justice Vikram Nath and Justice Sanjay Karol

Adv Pratiksha Basarkar, Adv Rishad Ahmed Chowdhury, Justice B R Gavai, Justice Vikram Nath and Justice Sanjay Karol

Nishad didn’t see the world outside prison for the next 13 years. After police custody expired, he was sent to judicial custody and was lodged in Thane Central jail. The case went to trial and in 2014, he was convicted and sentenced to death by the Thane Sessions Court. He approached the Bombay High Court to appeal; the HC upheld the conviction as well as his death sentence. He was subsequently transferred to the Yerawada Central Jail in Pune.

“As soon as I was able to, I arranged for pictures of Lord Shiva, Goddess Parvati and Lord Ganesh, and pasted them on the wall of my cell. Every day, I’d pray to them. It was my only source of strength,” says Nishad, who requested his family not to visit him. “I knew what it was doing to them, seeing me like this, especially with the death penalty confirmed. I had no wish to turn a knife in their wound.”

A year later, in 2015, members of Project 39A, a criminal justice research and litigation centre that is part of the National Law University in Delhi, visited Yerawada. When they learned of Nishad’s case, they expressed their interest in representing him.

The appeal was filed the same year, with Project 39A briefing senior advocate Mr. B H Marlapalle, who took the case on in the Supreme Court. Meanwhile, Delhi-based advocate Rishad Ahmed Chowdhury was the advocate on record for Nishad in the SC.

“We studied the case and found that there wasn’t a lot of evidence against Nishad. The entire case was only based broadly on three things. Firstly, the police had claimed that they had found blood stained articles, such as a towel and a mat at his house before his arrest. However, there was no evidence at all that the room belonged to Nishad or that he lived there. Details of the room, such as room number, were also unclear. Second, some clothes were said to be found based on Nishad’s statement from the same room. However, the police had already searched his entire house—a small room in a chawl, measuring 8.5 feet by 6.5 feet, the bathroom being 2.5 feet by 2.5 feet, once before for several hours and found nothing. Three days after his arrest, they went back again and returned with the clothes!” says advocate Pratiksha Basarkar of Project 39A. What made this evidence further unreliable was that Nishad’s statement was recorded in Marathi—a language he did not understand and was not explained to him in Hindi.

“Besides, the police claimed that his DNA was found on the victim. But there is no reliable evidence record of Nishad having been medically examined, which is a requirement for a person accused of rape. Nor is there any document to state that his samples were ever taken,” says Basarkar.

Another piece of evidence presented by the prosecution, she adds, was the fact that the victim’s father had expressed suspicion towards Nishad. The father, however, said in his deposition that he only started suspecting Nishad after the police arrested him. “So why was Nishad suspected in the first place? This is a complete mystery,” Basarkar says.

The gaps in the investigation were laid before the SC and earlier this month, in a rare instance, the Supreme Court overturned the Sessions Court and Bombay High Court verdicts, taking the view that the lower courts were swayed by the horrific nature of the crime.

“The Supreme Court rigorously scrutinised the evidence and found it entirely inadequate to support a conviction. The judgment also highlighted multiple illegalities in the investigation. We are seeing a significant number of cases where death sentences upheld by High Courts are being set aside by the Supreme Court, often through outright acquittals,” Chowdhury observes.

The Bench, comprising Justices BR Gavai, Vikram Nath and Sanjay Karol, minced no words in their order while announcing the verdict. “It is true that the unfortunate incident did take place, and the prosecutrix sustained multiple injuries on her body and surely must have suffered great pain, agony, and trauma. At the tender age of six, a life for which much was in store in the future was terrifyingly destroyed and extinguished. The parents of the prosecutrix suffered an unfathomable loss; a wound for which there is no remedy. Despite such painful realities being part of this case, we cannot hold within law, the prosecution to have undergone all necessary lengths and efforts to take the steps necessary for driving home the guilt of the appellant and that of none else in the crime,” the order stated.

For Nishad, what mattered was that his innocence was proven. And he had one more shot to see his ageing parents and four siblings. “The tears didn’t stop for long,” says Nishad, who reached his ancestral home in Siddharth Nagar, Basti division of Uttar Pradesh, after the formalities of his release were completed. “Especially after the death penalty was announced, sapne mein shamshaan dikhta tha. I kept seeing a cremation ground. I still do, sometimes. It will take a while for the nightmares to subside. Hum gareeb aadmi hain. Humko utna hi bolna chahiye jitni hamari pahonch hai,” he says about the injustice he endured.

Even as he struggles to free himself from the past, Nishad isn’t scared of plotting a future. “I’m trying to find the job of a driver. People rent their cars out for long distance trips and I’m talking to some of them. If that doesn’t work out, my family has been urging me to learn how to make mithaai and set up shop here,” he says.

A return to Mumbai will be emotionally taxing, he knows, but Nishad is a realist. “It’s a question of livelihood. If nothing works out, I’ll have to give Mumbai

another shot.”

For now, though, the priority is to let the scars heal. “I’ve been home for seven days but my younger brother still follows me around wherever I go. He hasn’t let me out of his sight.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!