A wildlife filmmaker is seeking to build a community of women who work in science and nature and deserve to be celebrated. After featuring over 100 women in India, the platform has recently started a Pakistan edition

Ashwini Bhatt is a reviewer with eBird India and a senior grade lecturer in anatomy

A few months ago, natural history filmmaker and Jackson Wild jury member Akanksha Sood Singh became part of the festival’s advisory board, and while developing a curriculum, attempted to reach out to women working for science and nature in India. “I could barely come up with 20 names,” she says over a call with mid-day. Singh started the Women of the Wild India page on Instagram, driven by the need to create a database of women working in the field in different capacities—as journalists, photographers, educators, scientists—on one platform. She wanted to document stories of their journeys, struggles and hopes, to encourage networking, help find opportunities, to offer advice and ultimately build a community to inspire and uplift a new generation.

ADVERTISEMENT

“There are a lot of people out there, but they are just not known, especially women,” says Singh. “I myself have worked in the field, which is quite male-dominated, and know the struggles one goes through in just trying to make oneself be heard and seen.” Primary among these struggles, she says, is the lack of parental support, associated both with concerns around instability and safety, the work invariably financially unrewarding, and demanding a degree of physical strain in remote areas, seen as unsuitable for women.

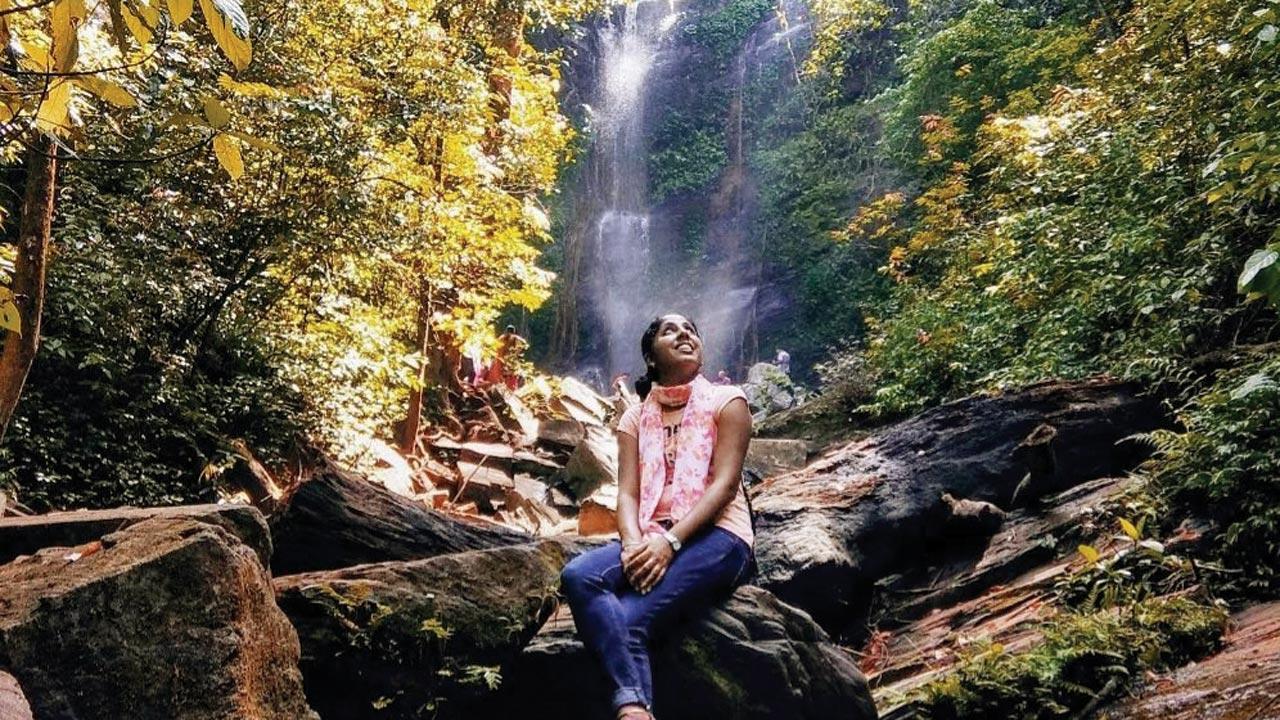

Tanvi Gautama is a PADI digital underwater photography instructor and works as a diving professional at scuba diving centre Temple Adventures in Puducherry. Lack of representation is the biggest issue in the scuba industry, she says, with just 35 per cent of its members being women. Pics courtesy/@womenofthewildindia, Instagram

“Everyone is here because there is a childhood connection with nature leading to a desire to take it up as a career option. But the barriers they face are the same across the board,” says Delhi-based Singh.

Kopal Thakur is a naturalist at the Kanha Tiger Reserve. “Sometimes, I am called ‘Kopal sir’ reflecting that there aren’t many women drivers in our forests,” she says, while also acknowledging that the Indian forest administration is undergoing a paradigm shift, encouraging women to enter the field and ensuring a safe environment for female guides and drivers

The page has till date featured over a hundred women, and recently started a Pakistan edition. It also hopes to initiate a series for women working in similar fields in Malaysia by the end of the month. Among the individuals featured are Anagha Devi, a self-trained odonate expert, who, given her conservative home, writes about her secret sojourns to photograph wildlife and join nature clubs, learning about odonates and birds and their curious egg-laying habits. There is Sneha Dharwadkar, a researcher and co-founder of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises of India (FTTI), who writes about how volunteering with urban wildlife rescue centres and rescuing herpetofauna paved the way for her career in wildlife, and the difficulties of being among very few women herpetologists; and Dr Safia Khanam, a marine biologist and assistant professor at the Centre of Excellence in Marine Biology, University of Karachi. Dr Khanam specialises in mangrove ecology, shell fisheries, biodiversity and taxonomy of marine invertebrates, benthic fauna of muddy and sandy shores, and the human component of marine ecosystems. She writes about working in areas along the coasts of Sindh and Balochistan to obtain data for coastal zone management, biodiversity and habitat conservation. “In the long run, the goal is to ensure continued access of natural resources by the coastal communities directly, and the larger population indirectly,” she shares on the page.

Akanksha Sood Singh

While recommendations have poured in, many women continue to be hesitant about being featured on the page, unsure whether their achievements merit such honour. “I’m very clear,” says Singh. “I don’t want to just profile women who have done great work. I want to feature every woman who is directly or indirectly connected to nature or science. Other people reading [their accounts] might relate to their story.” Anushka Kawale, profiled on the page, studied natural sciences at St Xavier’s College, Mumbai. She remembers being given a caterpillar to rear when she was 10, an experience that left a mark and was soon followed by outdoor activities and treks. But, it was not until she met like-minded people in college that she started to think of a career in the field. Kawale, who is now contemplating a career in science communication and research, discusses her parents’ concerns around safety in the field, exacerbated by stories heard from friends and colleagues. “But seeing other women overcoming these challenges and learning about how they have done it is also inspiring,” notes the recent graduate.

In the coming months, Singh hopes to use the page to host workshops on communication, storytelling, long and short-form filmmaking, release information about job postings and volunteer programmes, and profile institutions by inviting people who have worked with them to share their experiences. By next year, she also wishes the platform to enable an exchange of ideas, information and host online courses among the three countries currently part of the Women of the Wild series.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!