An environmental writer, artist and explorer uses the skills in her toolbox to document the country’s vulnerable landscapes, ecosystems and populations

Bombay’s western coastline is hemmed by rich reefs and rocky tidepools. Reclamation efforts and the new coastal road threaten these important but fragile ecosystems. Pic/Arati Kumar-Rao

The larger picture has started becoming abundantly clear about just what is happening in the Indian subcontinent. This is a systemic problem we are facing. This is a flaw in thought—about various aspects of governance and development in India and the subcontinent as a whole, and not a one-off occurrence,” environmental writer, explorer, photographer and artist Arati Kumar-Rao tells us, discussing the interconnectedness of the landscapes she writes about in her first book Marginlands: Indian Landscapes on the Brink (Pan Macmillan India, Rs 699).

ADVERTISEMENT

In the course of documenting the densely populated Ganga-Brahmaputra-Meghna basin with its large hydro power dams and barrages for example, she relates how while working in Arunachal Pradesh, she found she had to visit Assam to pursue a related thread and then that led her across the border into Bangladesh. “I was making my way through the landscapes and following one story, which was leading to another and then another, and trying to weave a fabric. It was clear that what was happening in one landscape had repercussions in another.”

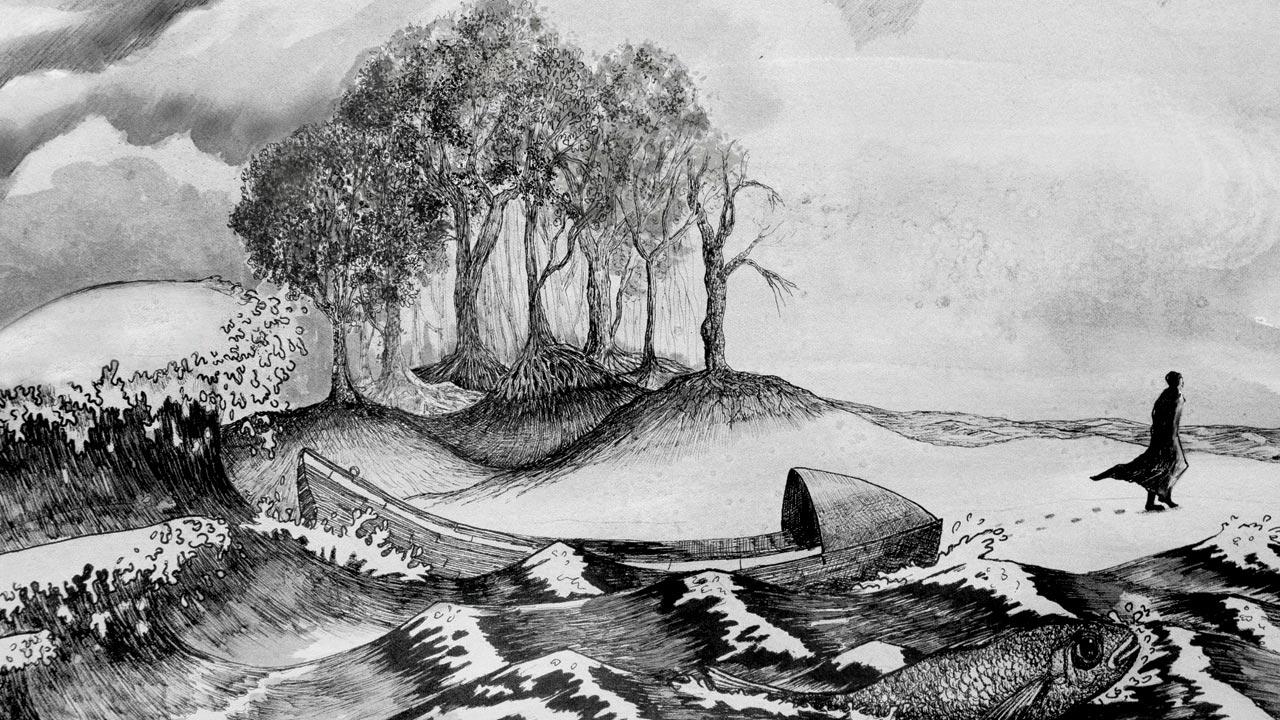

People living upstream and downstream of the Farakka Barrage often lose everything to the changed behaviours of the interrupted river. Pic/Arati Kumar-Rao

People living upstream and downstream of the Farakka Barrage often lose everything to the changed behaviours of the interrupted river. Pic/Arati Kumar-Rao

Starting work on the project in earnest in 2013, Kumar-Rao has journeyed into several of these threatened and vulnerable landscapes. The book’s scope ranges from the detailing of rainwater harvesting methods in the deep Thar and the poorly planned government projects that have disrupted the traditional food and water sources and livelihoods of the locals, to the struggles of the Gangetic dolphin to survive due to the impoundment by dams, to the crab-catchers in the Sunderbans threatened by man-eating tigers and the incursions into the Mumbai coastline, which has exposed the city to devastating flooding every monsoon. “I took the help of the inherently personal experiences in each landscape to shine light on the issue,” says Kumar-Rao, her narratives of immersive interactions with shepherd-farmers, crab hunters and other residents of ravaged lands offering deep inroads into their lived language, history and knowledge. “What I want to illuminate through my writing is connections,” remarks the author. “As a non-specialist, I have the unique opportunity to see beyond silos and make connections across disciplines and the environment is such a creature that it touches everyone and everything. We are part of it and making those connections is essential.” At the same time, she speaks of an interest in the history of the country which is intimately tied to the history of the environment of the country, and the alteration of its landscapes.

Quoting Prof Rob Nixon, Kumar-Rao writes in the book about “slow violence” which she describes as “a kind of destruction that unleashes itself incrementally, over seasons, often over generations. Unspectacular and sometimes imperceptible, it can be spatially dispersed: a disruption in one place can affect landscapes and lives several hundreds of miles away.” While her book offers many examples of such slow violence, the most illustrative instance, she believes, is that of the Farakka Barrage which was originally built in 1971 to stop the deterioration in the Bhagirathi-Hooghly, but ended up causing long term harm both upstream and downstream for 1,200 kilometres. “It’s geologically and temporally disparate with effects that are still continuing,” observes Kumar-Rao. “It is one of those classic examples of slow violence. When it was built, people didn’t know much. There were warnings but they didn’t heed them, and now it has caused so much angst, destruction, degradation, devastation, migration and ill health. What good has come out of such a drastic engineering solution is something to ponder about.”

Kumar-Rao says she was determined to upskill herself using art along with photography as tools to tell the story well. Pics Courtesy Pan Macmillan India

Kumar-Rao says she was determined to upskill herself using art along with photography as tools to tell the story well. Pics Courtesy Pan Macmillan India

But there is also the possibility of reversing a lot of the damage, she opines. “I am seeing an increasing number of people doing good work restoring ecologies. It is going to take effort, time, perseverance, will power and a lot of resistance, a revolution even, to be able to reverse a lot of the damage that has already been done but nature is immensely resolute.” She cites examples around the world of such damage being reversed, such as in the Pacific north-west of the United States where a dam on the river Elwha was pulled down to bring back salmon which had completely disappeared, because just like Farakka and the hilsa here, the salmon going upstream to spawn in the Elwha were interrupted resulting in the plummeting of the numbers. “They brought down the dam and slowly with good monitoring, the ecosystem has revived with the salmon numbers rising,” she notes. There is also the recent example of the decision to bring down the Klamath dam in the Pacific north west. “There are countries which are reversing some of the decisions that they had taken many years ago. We unfortunately are not at that pace or stage, but it gives hope that we can do it too,” she insists, while reminding that political will power needs to be there and the approach should be both, from the top-down as well as bottom-up.

Citing influential environmental writers like Nan Shepherd, Barry Lopez, Paul Salopek and Robert Macfarlane among others, Kumar-Rao speaks of the importance of environmental writing, the support of philanthropists like Rohini Nilekani who supported her book project, and the need for editors to invest in long-term storytelling. “Instead of running after GDP, if we actually protect what we have in terms of the land and the resilience of the land, our prosperity is going to be far longer lived. It is important to remember that the environment is not something that is ‘other’ than us, it is us. Environmental stories are therefore essential because they are the semaphores of where we are going.”

Arati Kumar-Rao

Arati Kumar-Rao

At the same time, she speaks of the feelings such work and writing has left her with. “One thing that weighed very heavily on me was that I could come back from those places of intense degradation and the very fact that I could leave was a privilege. I felt almost guilty that I could do that and that the people I was writing about couldn’t do that. I had seen such awful scenes and then you come back to a roof over your head, hot food on the table and a very different lifestyle and that is something I still struggle with.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!