A new memoir revisits the story of two dynamic families, the Padamsees and Alkazis, both fuelled by the dream to resurrect theatre in the country

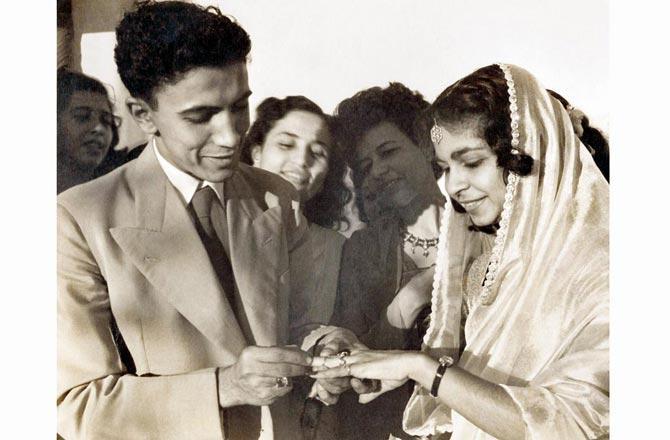

Ebrahim Alkazi and Roshen on their wedding day in October 1946

It was at a horseshoe-shaped dining table in 1943, that the story of English theatre in Bombay was first scripted, and with that, the fate of two families, the Padamsees and Alkazis. A group of college students, led by the enigmatic Sultan Padamsee, gathered around the unusual-looking table, which only boasted of curves and no edges, in the sprawling flat of Kulsum Terrace in Colaba Causeway, to discuss how they would start what they’d simply call the Theatre Group. This was the beginning of a journey that would have far-reaching consequences on the world of art and theatre.

It’s not surprising then that Feisal Alkazi, the son of theatre veteran and former director of the National School of Drama Ebrahim Alkazi, opens his new book, Enter Stage Right: The Alkazi/Padamsee Family Memoir (Speaking Tiger), with this episode. It’s a curtain-raiser to a grand story of two of the greatest theatre families.

Where it all began - the horseshoe-shaped dining table in Kulsum Terrace, as it is today. Pics courtesy/Alkazi Theatre Archives and Enter Stage Right: The Alkazi/Padamsee Family Memoir (Speaking Tiger) by Feisal Alkazi

Delhi-based Feisal, who is an educationist, activist and theatre director, having directed over 200 plays in Hindi, English and Urdu, began working on the book early in 2019, after he was approached by Renuka Chatterjee of Speaking Tiger to pen a family memoir. “For some strange reason, though I had written books before, it had never crossed my mind to write one [of this nature]. I mulled over it for about six to seven weeks, before meeting Renuka again.” For the next few months, Feisal wrote ferociously, dipping into memories of his time in Bombay spent at Kulsum Terrace with his grandmother Kulsumbai, and later at Vithal Court in Cumballa Hill, before he and his sister Amal moved to Delhi, after their father joined NSD. “In the beginning of last year, after I had completed most of the chapters, I went back to Mumbai, revisiting many of the places, where this story kind of began. My cousin, Ayesha Sayani, the filmmaker, had done these wonderful video interviews with my uncle Alyque [Padamsee], my mother [Roshen], aunt Candy, Khorshed Ezekiel [poet-playwright Nissim’s sister-in-law], and Gerson da Cunha. They were fantastic. She had them all transcribed, and given to me, saying, ‘They are all yours’,” says Feisal, in a telephonic interview. This was also important, he adds, because the book goes back a generation, to his grandparents’ time, before exploring his parents’ early beginnings in the world of theatre and art. “The first 10 chapters happen before I am born… That [Sayani’s videos] helped me fill in a lot of the blanks, which I had about the 1930s and 40s.”

Kulsumbai, Roshen’s mother and Feisal’s grandmother, becomes the wheel, driving this story forward, mostly because her role seems indispensable in her children’s early years, which eventually shaped their love for the arts. She was the second wife of Jaffer Ali Padamsee, and belonged to a wealthy and progressive family from the Khoja community.

The Padamsees with the three sons-in-law, Deryck, Ebrahim, Hamid, and Alyque Padamsee (standing, from left to right)

She was “determined to give her children the best possible English education”. “As each child reached the age of four they were sent off to an exclusive, elitist residential school in Bombay itself. Here they rubbed shoulders with royalty: the Scindia boys, Princess Diamond and Princess Pearl of the Rajpipla family,” he writes in the book. Feisal agrees that Kulsumbai, inevitably became the protagonist of this memoir, otherwise peppered with so many dynamic characters. “Anybody who ever encountered her [would feel the same]. I didn’t put this in the book, but when MS Sathyu was trying to finish Garam Hava, he didn’t have money and turned to my grandmother. She gave it to him, and he took it, forgetting that she is a businesswoman. And then, she said, ‘It’s 25 per cent [interest] a month’,” he laughs. “She was a very tough nut to crack. What was beyond belief for me was how she dealt with her sons, who married women they slept with and that too in the bedroom next to her. While she was okay with them being her sons’ girlfriends, and calling her ‘mumma’, once they were married, she didn’t allow them into the house. It was something I found so unjust and incorrect,” he shares. “But that made her a strong influence. If you read Alyque’s book [Double Life], you will learn that his mother was the woman, who inspired Lalitaji in the Surf commercial. It’s interesting, when you think of how could such a strong woman emerge in that time, and deal with quite a philandering husband [Alyque suggested his father had eight mistresses over the years], and decide at some point, to pack her bags, take all her children, get into a boat, and go to England [for their education]. That was quite a formidable decision for a woman to take in the 1930s.”

She recoiled when her eldest son, her “golden boy,” Sultan, known otherwise as Bobby, died by suicide, after taking an overdose of sleeping pills. He was just 23. “I don’t think the family ever came to terms with his death. My mother always said, ‘Those who the gods love die young,’ but that’s not a clear answer at all. Till very recently, being gay was considered taboo. So, one wonders what it was like for Bobby to be gay then. My aunt Candy told me recently, ‘The problem with my mother [Kulsumbai] was that her extended family had a lot of gay men.’ So, while it was an open secret, nobody knew who his partners were. When he died, the family gave out a story that he was killed in a car accident. That was considered most acceptable then.”

Feisal Alkazi

A significant part of the memoir, however, is dedicated to Feisal’s parents Alkazi and Roshen. Alkazi’s father was from Saudi Arabia; he travelled to colonial Bombay for better business prospects. Alkazi, who was a close friend of Bobby’s, took over the reins of the Theatre Group, after his passing away, and later, married his sister, whom he had fallen in love with. The couple separated when Feisal was eight years old, but their association didn’t end, as Roshen continued to design costumes for his shows. In 1977, when they were in their fifties, they even opened the gallery, Art Heritage, together, and later, set up a home in Kuwait. Alkazi’s partner Uma Anand never disturbed this equation they shared. “They met each other in their late teens. So they had grown up together, and gone through formidable circumstances.

She was so much his intellectual companion all the way through, because she was so bright and dynamic, and had an enquiring mind,” shares Feisal. “I think my parents had great respect for each other. Also, the family ties were very close. Even when he moved in with Uma, he was never kept away by the extended [Padamsee] family. The same was with my father’s family. He also never tried introducing Uma to either of the households, or even us. My parents were always seen as a couple. Perhaps, that helped. Looking back, it was never a broken relationship, though unusual.”

Tragic genius - Bobby Padamsee at home in Bombay with his trophies, 1944

While Feisal says that his mother was a strong influence in his life, his father was conspicuously absent during his growing up years. “It is a conversation I later had with him, because I think, it’s very important for children to have their father around. Did I hold it against him? Well, quite frankly, he had made a choice, and I will just say that I respected it. I never had ill-will towards his partner, Uma. I realised from my own experience, that you are in a one-parent

family, and it’s not the end of the world at all.”

What he was consciously aware of when writing this memoir was that he didn’t want to make it a “no-holds-barred” book. “I didn’t want any skeletons to come tumbling out of this book. I am not that kind of person, and I believe that everyone has the right to their private life. I feel that ‘what happens in the family should be kept within the family’. So, while certainly this isn’t a censored account, there are many stories that haven’t been told, and I don’t intend to tell them.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!