Why did the legendary director Mrinal Sen fall out with his equally talented friend, Ritwik Ghatak?

A lighter moment during the making of Antareen. PIC/SUBHASH NANDY

He was always surrounded by friends, though the nature of the circle changed over time. In the early days, they were all fellow travellers, equals, with similar views, similar ambitions, similar trajectories. Many from that group drifted away over the years, for various reasons. Tapas Sen was the only one who stayed close all through my father’s life. Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Salil Chowdhury moved to Bombay and became part of the commercial film world. Though every time they met my father, which was no longer very often, I could still see a spark of the old camaraderie.

ADVERTISEMENT

Whenever Salil-kaka came home, he and my father would ask each other about common friends from the IPTA days. Sometimes Salil-kaka would sing songs from their activist past. But it was also clear that they lived in different worlds now, that the only common thread was the nostalgia for their time together, when they shared the dreams of a revolutionary future.

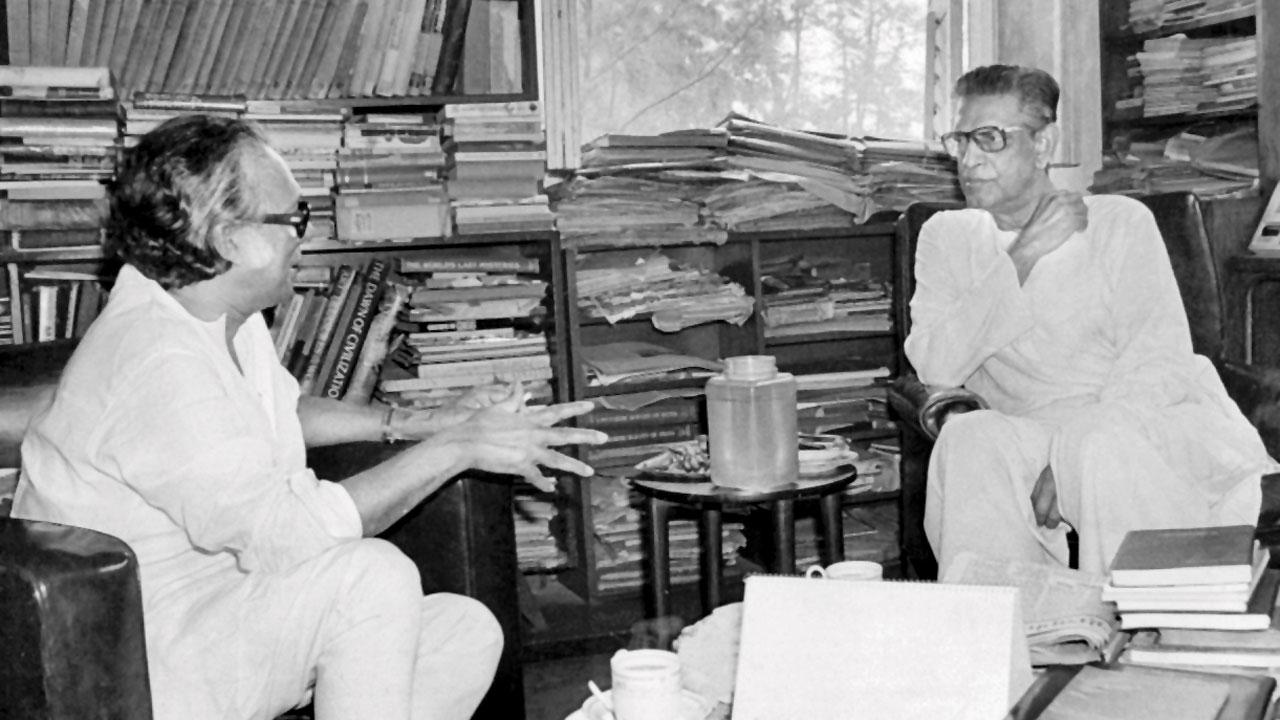

Mrinal Sen and Satyajit Ray

My father would sometimes stay with Hrishi-kaka in Bombay. Once, when I was four or five, my father took Ma and me to Bombay, and we all stayed at Hrishi-kaka’s Andheri home. Later, Hrishi-kaka’s son became a good friend of mine through a shared interest in electronics, and I’ve stayed quite a few times at their beautiful sea-facing bungalow in Bandra. However, my father and Hrishi-kaka were making different kinds of films, and slowly it was but inevitable that their intellectual lives would drift far apart.

Ritwik-kaka stayed in Calcutta, and though he and my father were both trying to make films with the same objective, another force was pulling them apart—Ritwik-kaka’s severe alcoholism. I don’t recall ever seeing him sober. No one in my immediate surroundings drank. Therefore, as a child, I was both curious and afraid of drunkenness. Whenever he came to our house, he would be senselessly drunk and abusive, often accompanied by people who could hardly stand straight. I don’t recall a day when he and my father had a normal conversation. During my high-school and early college days, on numerous occasions, local boys would knock on our door and report that they’d found Ritwik-kaka lying drunk somewhere. It was then my job to organize a rickshaw to take him home. I was afraid of him if he visited us when my father was not home; he would engage in incoherent and dismissive conversations about my education. Unfortunately, Ritwik-kaka and my father, who could have had the most meaningful conversations, never did so in their later years. They occasionally met, there were casual exchanges of information, but those lacked any kind of depth. The constant veil of an alcohol-induced haze made impossible any meaningful communication.

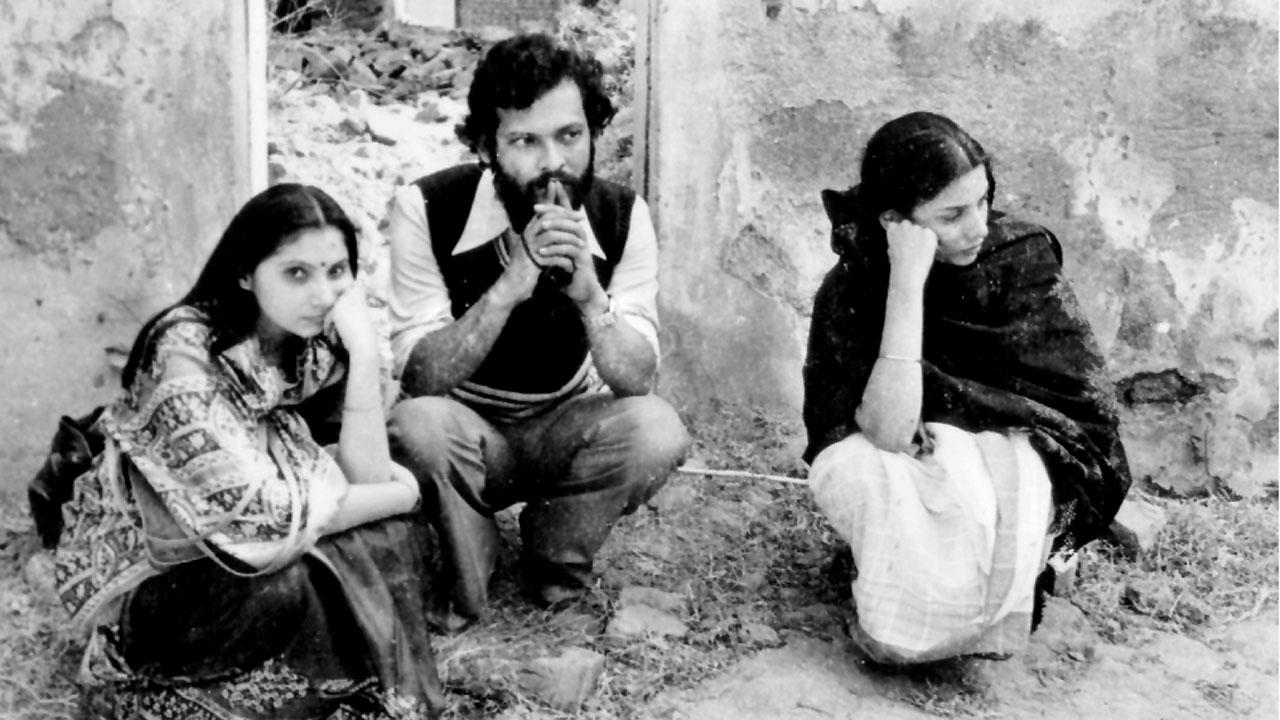

Kunal Sen and his wife, Nisha Ruparel-Sen, with actor Shabana Azmi, during the shooting of Khandhar. PIC/SUBHASH NANDY

Kunal Sen and his wife, Nisha Ruparel-Sen, with actor Shabana Azmi, during the shooting of Khandhar. PIC/SUBHASH NANDY

In the winter of 1976, after many such incidents, Ritwik-kaka was admitted to the hospital for what would be the last time. My father was beside him when he died. His wife, Surama, taught in a school far away, trying to protect her three children from the chaotic life he had created. All of them came to Calcutta and stayed with us until things settled down. It was as if we were one big family. What his addiction took away, it tried to return on his death. When my mother died, I found a tattered letter addressed to her from Surama Ghatak, in which she’d written about the deep bond between the two families. My mother, for some reason, saved the letter in her handbag. I will never understand why we have such romantic notions about extreme addiction among artists.

It is nothing but a disease that destroys families, destroys integrity and ultimately destroys humanity. Even though his earliest circle dissipated over time, my father continued to surround himself with friends. My earliest memories are from the early sixties, when we lived in a tiny two-room ground-floor flat on Manoharpukur Road. The living room was small, almost entirely occupied by a sofa bed and a few low cane stools or moras. And by visitors who came to my father throughout the day, friends as well as co-workers from his latest production. The friend circle in those days comprised people connected with the film-society movement, writers, family friends and artists. As far as I remember, the topics of their conversation spanned cinema, politics, literature and everyday banter. My father wasn’t that successful yet, so there were no fans or admirers.

That changed after his success in the late sixties and early seventies. I was older by then, and since that small living room was also where I was supposed to study, I became a silent participant in those conversations. There was a growing group of visitors who admired his work. Some were genuine well-wishers, but an increasing number hoped to benefit from the alliance or simply enjoyed belonging to a polarized camp. I am not sure my father could distinguish these factions as easily as I can today, in hindsight.

Praise can be a potent tool to blunt one’s ability to judge the real intent of people. Bengalis have a strange propensity to split any position into two opposite camps. Be it the support for a football team or the way a particular dish should be cooked or how a song should be sung, we indulge in strictly binary choices. If you belong to one side, you must oppose the other with all fury. The same thing happened then: people would champion my father while being unnecessarily critical of Satyajit Ray, with the reverse happening in Ray’s circle. A few people had access to both households, and they carried the conversations from one living room to another. They enjoyed the reactions they provoked. I think both Ray and my father were very respectful of each other, but this poisonous atmosphere did stain their thinking. Such is the power of sycophancy.

Excerpted with permission from Bondhu: My Father, My Friend by Kunal Sen, published by Seagull Books

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!