A photobook and accompanying exhibition, born out of a photographer’s family album, uses memory as a tool to explore the role of matrilineal bonds in shaping female identity

Sheetal Mallar

I wanted the viewer to make this book their own. I was hoping it would evoke emotions, their own emotions so that it would mean something more than just someone else’s story,” photographer-model Sheetal Mallar tells us about her photo book, a repository of memories of her grandmother who passed away in 2019. Photographs from this self-published book were exhibited at the India Art Fair this February and will now be shown in an exhibition titled Braided opening at Art Musings on April 11.

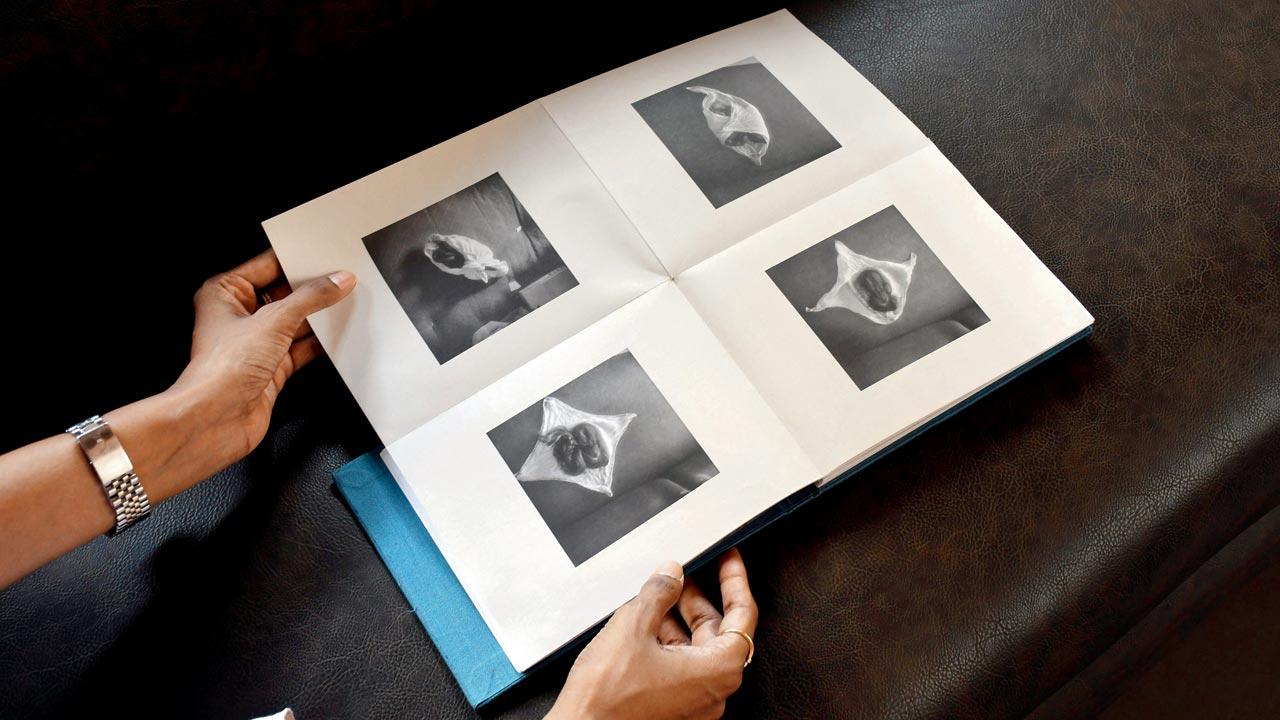

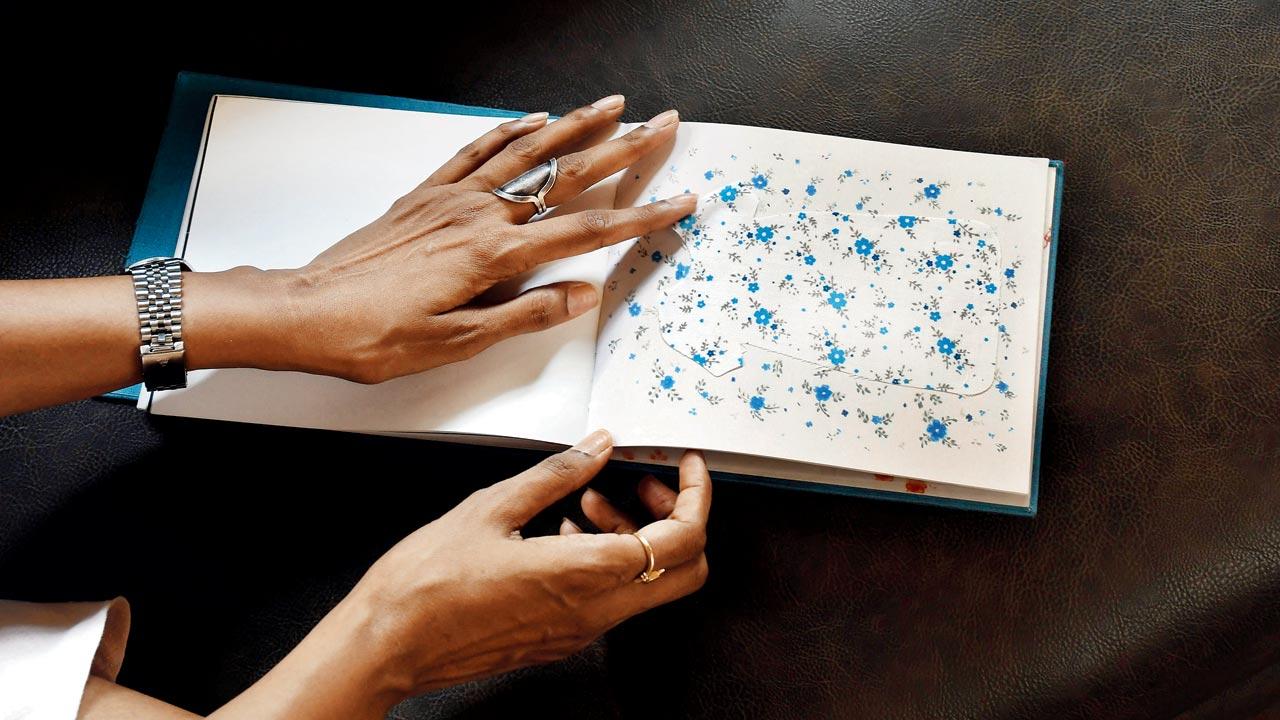

Sheetal Mallar’s book has a tactility rendered by features such as pasted fabric swatches and folds or “windows in the book” . “I felt that these elements made you engage with the book at a slower pace because you have to pause, and open and close the folds. They may lead to emotions that words, pictures or even drawings often can’t evoke, and at the same time set the pace of the work which is quiet, still and introspective in nature,” she says. Pics/Kirti Surve Parade

Sheetal Mallar’s book has a tactility rendered by features such as pasted fabric swatches and folds or “windows in the book” . “I felt that these elements made you engage with the book at a slower pace because you have to pause, and open and close the folds. They may lead to emotions that words, pictures or even drawings often can’t evoke, and at the same time set the pace of the work which is quiet, still and introspective in nature,” she says. Pics/Kirti Surve Parade

The occasion will also see the release of the book which, Mallar tells us, has been 12 years in the making. “Initially, it was a playful way of spending time together as a family, dressing up and taking pictures. It was more like a family album. I wanted to put things together because of the transient nature of all the people you love who won’t be around,” says the artiste who took on the mantle of family photographer early on. ‘Amma’, Mallar’s maternal grandmother, was the only one, she says, who came from their ancestral village in Karnataka to stay with the family in Mumbai; the closeness forging a deep and nurturing bond between the artiste, her mother and her grandmother. “I wanted to look at the bonds we share with our maternal lineage. I believe it is a circle that is just as vulnerable, as it is strong. It’s been cathartic for me, looking at relationships that have been at my core.”

It was only after her grandmother passed away that she started compiling the pictures, combining them with drawings made over the years as the book slowly transitioned from an album to her first book. “I felt that one chapter was over. You never really get closure but it became a way to hold on to all the happy things that you loved about each other and all that you now miss.”

A photograph from a dress-up ritual. “We pretended to go to an imaginary wedding,” Mallar tells us

A photograph from a dress-up ritual. “We pretended to go to an imaginary wedding,” Mallar tells us

Braided, as its title suggests, is a layered work, bringing together different creative elements—text, photographs, with outlines of figures cut out to denote emptiness and loss and drawings. Photos of objects evoking Mallar’s grandmother’s physical presence—a comb, a television remote, silk sarees, bangles—are peppered through the book. There are pages with floral printed fabric, reminiscent of her ‘nighties’, pasted on them. “The nightie, especially here in India, is so readily associated with grannies. So, I cut out that fabric in the shape of a nightie and drew around it on the page. It felt like it started living within the world of that story. You can’t explain these things; it’s nicer that the tactile element brings about that emotion without you saying anything about it.”

Hair becomes another central idea in the book as photographs of hair of different colours and textures, hair that is tied or allowed to fall freely, and even a text snippet about cutting her hair while she lay asleep, feature throughout. “I wanted to use it metaphorically in the work because I felt that the braiding rituals that we have with our moms create a real bond because of how long it takes, the physical closeness of the act and the conversations that take place during the process. As a child, I used to be completely fascinated and watch my mother and grandmother when they did their hair. For me it would mean so many things—it would mean they were in a happy place, that they were looking after themselves. When my grandmother stopped being able to do her hair, I correlated it to everything that she must be feeling—that she’s not in her body anymore, that she’s getting older and things are changing.”

A photograph Mallar associates with rituals around hair and the memories connected with them that we carry with us

A photograph Mallar associates with rituals around hair and the memories connected with them that we carry with us

Mallar also shot on expired film to evoke the idea of fading memories, the result she says of playing with the medium. “It’s a personal project and I didn’t have any time constraints. [Using] It gave it this dreamlike quality. I thought even if it looks wrong, it’ll look wrong beautifully. Everything was a surprise in a sense, but I could afford that with this work.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!