Unemployment, inability to deal with a woman who has agency, pressure that comes with years of patriarchal conditioning—are just some of the reasons men need support and counselling, before they end up releasing the monster inside them

Illustration/Uday Mohite

"He killed my sister mercilessly. Then he sat next to her body and kept asking her, ‘Kyun kiya, kyun kiya [Why did you do this to me]’. That is the question I want to ask him—why did he do this to her? She had done nothing wrong,” says Saniya Yadav, 16, recounting the gruesome murder of her elder sister, Aarti, at the hands of her ex-boyfriend Rohit Yadav in Vasai on June 18.

The murder made headlines across the country and social media was rife with videos of Rohit, 29, bludgeoning Aarti, 22, repeatedly with a spanner in broad daylight as passers-by merely watched agape or took videos of the crime.

“I watched the video. He struck her from behind, and kept hitting her in the head. Aarti tried to escape once, but he continued to hammer down on her,” says Saniya.

Saniya said her sister Aarti (right) and Rohit broke up after a financial disagreement and suspicions that she was cheating on him, but he continued to stalk her

Saniya said her sister Aarti (right) and Rohit broke up after a financial disagreement and suspicions that she was cheating on him, but he continued to stalk her

The sheer brutality of the crime prompted the same question in the minds of all who watched the videos or read reports about the deranged attack: Why?

Police told this paper that Rohit and Aarti had been together for six years but broke up recently after disagreements about money and his suspicion that she was having an affair. Rohit told the police that he had wanted to marry Aarti, but her father insisted he would only allow the marriage once the 29-year-old bought a house.

“Rohit was saving up for the house. He used to do odd jobs at different places, and earned about Rs 10,000 per month, most of which he would hand over to her family to keep aside for a house. But things got difficult after he lost his job,” said the police.

Rohit sat by Aarti’s lifeless body for 10 minutes, yelling abuses at her until the cops arrived on the scene. Pics/Hanif Patel

Rohit sat by Aarti’s lifeless body for 10 minutes, yelling abuses at her until the cops arrived on the scene. Pics/Hanif Patel

Sources close to the case said that around this time, Aarti had started working at a computer class in Vasai, to support her family after her father fell ill and his paani puri business shut down. As the sole breadwinner of the family, she would hand over her entire salary of R8,000 to her family, paying for her father’s medicines, as well as the education of her sister Saniya, who had just started Class X.

A distance had crept in between Aarti and Rohit, however, and he began to suspect that she was having an affair with a co-worker. “Rohit saw this as a huge betrayal,” said police sources, adding, “She was like his family; he had no one else. He had lost both his parents and his sister at a young age. He didn’t have any close friends either.”

Rohit told the police that when he confronted Aarti, she told him to “go die” and that there was no space for him in her life. He told the cops that after this, he had tried to take his life twice, but failed. It was then that he planned the murder.

Harish Sadani, co-founder and executive director of Men Against Violence & Abuse

Harish Sadani, co-founder and executive director of Men Against Violence & Abuse

Aarti’s family, however, have denied that she was having an affair and said that Rohit would obsessively stalk her even after he and Aarti had agreed to part ways because of financial troubles.

“Rohit lied and lied. He lied about having a degree, a good job, money. That is why my father insisted that he should at least have a house before marrying my sister. Why would we send Aarti with someone who has nothing to his name?” questions Saniya.

“When Rohit said he would not be able to buy a house, he and my sister agreed to part ways. Then why did he continue to call her and follow her? A week before the murder, he assaulted her in a rage and even broke her phone, accusing her of an affair. This was also a lie. She got killed over a lie,” says Saniya.

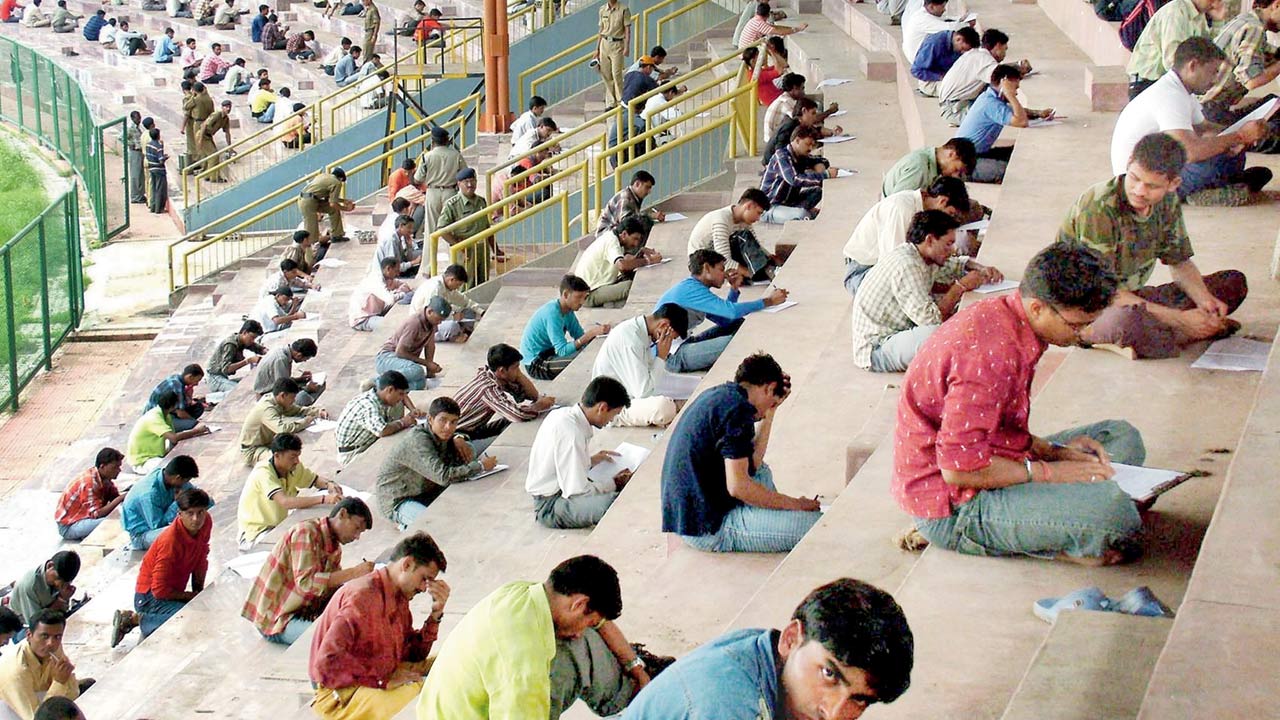

A file pic of young Indian men taking an entrance exam, hoping to secure for one of 1,500 vacant posts in the Madhya Pradesh State Police Department in Bhopal amid rising unemployment in the state. Pic/Getty Images

A file pic of young Indian men taking an entrance exam, hoping to secure for one of 1,500 vacant posts in the Madhya Pradesh State Police Department in Bhopal amid rising unemployment in the state. Pic/Getty Images

“Aarti had every right to make her own decisions. Rohit has ruined so many lives. The girl is dead, her family is devastated and he has ruined his own life too. How do we give justice in this case?” questioned an officer close to the investigation.

The Vasai murder is among a string of violent episodes in recent times that have sparked a discussion on poor men’s mental health. It doesn’t help, say experts, that men are often under crushing societal pressure to be “strong, silent providers of the family” in an increasingly tough economy.

A 2014 study on intimate partner violence in India, conducted by US-based International Center for Research on Women and United Nations Population Fund, found that men who experienced economic stress were more likely to perpetrate violence on their partner. The study found that 55 per cent Indian men reported economic stress, which was defined in the study as stress or depression from work or income deficiencies. Crucially, 40 per cent of men who had economic stress said they had been violent with their partner in the last 12 months leading up the study.

Tara Kaushal, Nilay Kumar, Paras Sharma and Dr Hvovi Bhagwagar

Tara Kaushal, Nilay Kumar, Paras Sharma and Dr Hvovi Bhagwagar

The study stated that unemployment, not earning enough or even earning less than their female partner can all be causal factors for men being violent with their partners. The study posited that this was due to Indian notions of masculinity and the expectation that men are the primary economic providers of the household, even in situations where the woman works as well. In fact, the study found 38 per cent occurrence of partner violence by men who earned less than the woman, compared to a lower 34 per cent among men who earned more. In 2024, the instances may have increased.

Unfortunately, such cases are seen on the daily by cops and activists who work with victims of domestic violence. Aparna Joshi, police inspector (Crimes Against Women Cell), says, “Most cases I encounter stem from family conflicts, particularly between the wife and her in-laws. However, financial stress is also a common factor, often due to house loans. The male ego is fragile, and salary and money are definite sore points. These days, when both husband and wife are working, women are less willing to tolerate bad behaviour or compromise. Women are increasingly becoming independent, and the expectations from both in-laws and husbands are higher, leading to quarrels. Out of ten cases we handle, around three involve financial issues. In many of these cases, the man is under financial stress or feels his ego is hurt if the wife earns more.”

Activists working with victims point out, however, that men are not the only ones under pressure and, yet, they are most commonly the perpetrators of violence. “Women are also under immense societal pressure and so many women now support their homes financially—they face the same kind of stress. But we rarely hear of women assaulting others,” says activist Yogita Bhayana, who heads People Against Rape in India (PARI).

Ajit Ranade, Audrey Dmello and Deepika Bhardwaj

Ajit Ranade, Audrey Dmello and Deepika Bhardwaj

Others are wary of attempts to ascribe financial pressure as a cause of such violence. “In the past, we said alcohol was the problem. Then we said dowry is the problem. Now, we’re saying financial stress may be a cause. We must stop making excuses for violent men. These men lash out because they have this kind of violence inside them and they find soft targets in women and children,” says advocate Audrey Dmello, director of Majlis, an organisation that offers legal and social support to victims of sexual and domestic violence.

On Wednesday, just a day after the Vasai murder, yet another woman was killed in a similar dispute in Virar. In this case, the perpetrator was her son-in-law, an unemployed alcoholic. He would often beat his wife in drunken stupors, so she had left him and moved back to her mother’s house. Sources familiar with the family said the man, Prashant Khaire, was struggling financially ever since his wife—a working woman—left him. He would keep trying to convince his mother-in-law to send her back to him. It was during a similar altercation that he ended up killing her. “He grabbed a kitchen knife, tied her up and repeatedly stabbed the elderly woman in the stomach and neck, right in front of his two sons, aged eight and 10,” said senior inspector Vijay Pawar.

The conversation around economic stress, mental health and their link to violence is uncomfortable, but it is one we must have, say experts.

According to equal rights activist Deepika Bhardwaj, it’s not wrong to say that the pressure is disproportionately higher on men. “A huge number of families still run on men’s income. Men are brought up hearing that they must earn lots of money to support their families. The pressure to do well starts right from childhood,” she says, adding, “There is no justification for violence, but when we look at incidents like the Vasai murder, we only see what’s on the surface. We have no idea what’s going on in the backdrop, and that is something we must discuss too.”

Men have a higher chance of buckling under this pressure for two major factors—for one, Indian notions of masculinity presume that the man must be the “karta” of the family and provide for it financially and maintain control over family members. To add to that, any expression of vulnerability is immediately perceived as failure, says Harish Sadani, co-founder and executive director of Men Against Violence & Abuse (MAVA), an organisation that works to sensitise young men and prevent gender-based violence.

“These pressures are very real for men. When I ran a helpline 10 years ago, a major chunk of the calls were related to such stressors. Many of these men were suffering from great internal turmoil, but were unable to share it because it is frowned upon for men to disclose such intimate details even with their close male friends,” he says.

There is a woeful dearth of safe, non-judgemental spaces for men to open up and talk about what distresses them, and without this healthy outlet, many turn to alcohol or substance abuse, compulsive exercising, porn addiction or even self-harm and violence in the most extreme cases, says Harish.

“Look at farmer suicides; the trigger is economic, of course, with debts. But it also leads to the farmer seeing himself as a failure for being unable to support his family. It was a farmer’s son who pointed out to me that men account for most farmer suicides,” he emphasises.

Data released by NCRB last year showed that of 5,207 farmer suicides in 2022, as many as 4,999 were male, while 208 were female.

“We need to teach men that it is not all on them. Families can be supported by men and women. Men should no longer be brought up hearing only that they are the karta,” says Sadani adding, “We should also change how we raise our boys to look at women’s agency. In India, boys grow up never hearing the word no from their parents. As adults, too, they expect the same from the world and are unable to deal with rejection.”

For Hardeep Singh (name changed), a 37-year-old businessman from Gurgaon, quitting his job was at the centre of why his marriage fell apart. “When we got married 10 years ago, I would pay for everything. My wife was not earning well and she had a R10 lakh education loan. I paid off that loan and supported the family. But when my brother went into kidney failure and I left my job to take care of him, all the problems began,” he recalls.

“My wife and in-laws would taunt me, saying other men support their families but I had no job. They never treated me with respect and made me feel like less of a man,” Hardeep adds.

Now, the couple are in the midst of divorce proceedings, and it has been four years since he last saw his daughter, even though the court gave him visitation rights. “This is how our society is; when the husband does not earn, society will say he is not a man. I was depressed and suicidal. I had no one to turn to. I could not even face my friends because I felt ashamed, felt like I was a failure,” he recounts, adding that he eventually consulted a psychologist and felt better after therapy.

This feeling of shame and being unable to share one’s distress with friends or ask for help is a common marker of poor coping mechanisms and is the reason men have fewer healthy outlets for their frustration, say psychologists.

Psychotherapist Dr Hvovi Bhagwagar recalls one of her cases: “Soon to be married, Sanjay [name changed] had been brought to the clinic by his concerned family. He had picked a fight at a bar and spent a night in jail.

In therapy, he broke down and admitted the tremendous pressure he was under. He was on the verge of being laid off from work, had huge loans to repay and responsibilities of supporting ageing parents. When asked why he hadn’t shared this with his family or sought any support he said, ‘How could I? What will people think? Am I so weak that I cannot even take care of my family?’ Sanjay’s reluctance to share his struggles reflects the stigma surrounding vulnerability and the fear of appearing weak in our Indian culture which values stoicism and toughness in men,” she says.

From a young age, Indian boys are given the dual mandate to “grow up, earn and support the family” and to “face up, man up, and be tough”, she says, adding, “In the absence of healthy coping mechanisms, these pressures can sometimes manifest in acts of aggression or violence.”

The problem is just as much about economics as it is about mental health. While jobs remain scarce in India, the country also lacks the safety net that other nations provide in the form of unemployment insurance, says economist Ajit Ranade.

“In India, joint families typically support individuals who lose their jobs. In the absence of family, the stress on an unemployed person can be significantly greater… In India, we have an unemployment dole, or berozgaari bhatta, but it differs significantly from social security systems abroad. Most unemployed individuals in India rely on family and friends for support,” he says.

“Another notable difference is the rate of food inflation; while it ranges from 2 per cent to 3 per cent abroad, it can reach up to 10 per cent in India. The societal pressure on men to secure employment is quite high, as jobs are closely tied to human dignity. This pressure can have severe psychological impacts, with the stigma of unemployment being especially harsh on men,” he added.

Sociologist Nilay Kumar echoes, “The stigma of a man being out of a job is a largely unaddressed issue. It is almost taboo for a married man with a family to be unemployed. Although, it can happen to anyone and is fairly common.”

“In India, the job market is quite grim. Unemployment is not always due to a lack of skill but because of the volume of people who apply for a single position. Only about 5 per cent of India’s population is skilled. And around 75 per cent of technical graduates and 90 per cent of other graduates are considered unemployable, with men forming a significant portion of this group. Societal pressure on men to be employed is much higher than on women, creating a negative impact on both genders,” Kumar says.

Last month, former chief economic advisor Dr Kaushik Basu claimed that India’s youth unemployment rate is among the highest in the world, citing data from think tank CMIE that showed India’s youth unemployment rate had hit 45.4 per cent. The total unemployment rate for the country is 7.6 per cent, as per the same data. Meanwhile, data from the Directorate General of Employment shows that the male unemployment rate was 3.3 per cent in 2022-23.

This pressure has, in the past, also boiled over into riots over jobs. In 2022, protestors set a train ablaze and pelted stones at another in Bihar to protest non-transparent recruitment by the Railways. Amid the violence, the government suspended recruitment for 35,000 railway jobs, for which more than one crore candidates had applied.

Ritu Dewan, developmental economist and president of the Indian Society of Labour Economics, believes that men cannot hope for the usual jobs anymore. “The first thing we must realise is that there is no hope for a regular job anymore. There is a decline in the availability of regular jobs, and even casual work is on the decline. This has nothing to do with the pandemic, and everything to do with demonetisation. The lack of jobs led to a rise in self-employment, but with the chaotic system of GST, even those small enterprises started to go out of business.”

Dewan quoted a report published by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in March that painted a grim picture of unemployment in the country, stating that youths make up 83 per cent of number of jobless Indians. “This is not to justify any acts of violence, but living with no hope of a job, no hope of having a family, no hope of supporting your aging parents—it is unimaginably stressful. Almost every single day, in Mumbai alone, we hear of businessmen dying by suicide. It is happening at an unprecedented rate, and this is in the middle class. So, you can only imagine the plight of workers,” she said.

So, what’s the path ahead? Psychotherapist Bhagwagar says, “We need more open dialogue and conversations around debunking gender norms. It’s encouraging for me as a therapist to see that there is increasing awareness and discussion about men and mental health, especially during Men’s Mental Health Month in June. Also, we as a society need to normalise help-seeking behaviour for men. Therapy, stress management workshops, or support groups can give those opportunities for men to share experiences, receive validation, and learn coping strategies from others facing similar challenges.”

Paras Sharma, director of The Alternative Story, which provides counselling services, says there is a great need to talk about men’s mental health, as well as a need for more men to enter the mental health space. “There are just a handful of male psychologists who practice as therapists in the country. “Whom can a man approach if he needs to speak to someone and is uncomfortable being vulnerable before a female therapist?”

Sharma is among a handful of therapists who shines a light on men’s mental health on social media and also raises awareness about it via podcasts and blogs. He, too, says the need of the hour is to build safe spaces for men to vent their frustrations safely. Next month, he says, The Alternative Story is starting a support group for men called Brocade. “It’s a play on bro code and the many tapestries or forms of healthy male relationships. The goal is to explore emotional intimacy in male friendships, which is the cornerstone of female friendships, but always seen through the lens of homosexuality among men. But there is another term—homosociality—which refers to same-sex friendships. And this is what we must explore,” says Sharma.

Tara Kaushal, author of Why Men Rape, says, “Men are going to feel more and more that world is against them—not having money, job, not being able to buy a house. Then it becomes a spiral. You don’t get the house, don’t get the girl. The empowerment of women is also going to be an additional reason for their rage. The only thing we can do is help men handle their emotions better. We can’t give them a house, we can’t force women to be with them, but we can teach them to take rejection on the chin.”

Inputs from Anand Singh and Arpika Bhosale

45.4 per cent

India’s youth unemployment rate in 2024

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!