How do you replicate play between ghazal poet and audience on paper? Ranjit Hoskote shares the process of bringing 18th-century Urdu poet Mir’s verses to an English audience with a new translated collection

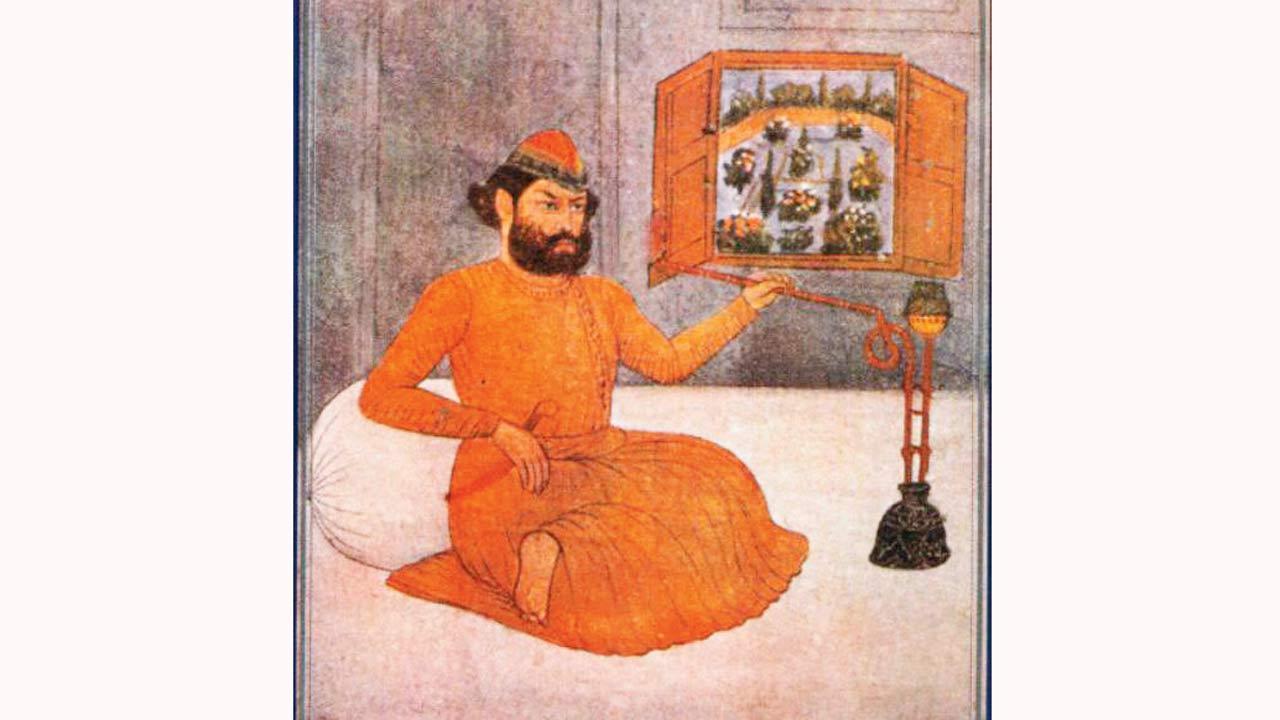

Unlike Ghalib, there are no photographs of Mir Muhammad Taqi. All we have are paintings of the Mughal-era Urdu poet

Ek jagah par jaise bhañvar haiñ lekin chakkar rahtā hai/

yaʿnī vatan daryā hai us meñ chār taraf haiñ safar meñ ab

(Like the whirlpool, still centre of a giddy circling/

the homeland’s an ocean on which we’re scattered in all directions)

Mir Muhammad Taqi composed this Urdu verse in the 18th century, but he may as well have been writing about our world today.

More than 200 years after his lifetime (1723-1810), Mir’s words strike true, as Mumbai poet, translator and art curator Ranjit Hoskote brings the she’rs to an English audience with a new translated collection, The Homeland’s an Ocean: Mir Taqi Mir (Penguin Random House, India).

Mir, considered one of the greatest Urdu poets, lived through extraordinarily turbulent times. The Mughal empire was collapsing amid raids by Afghan king Ahmed Shah Abdali and the East India Company closing in. Mir called Delhi home, but spent over a decade in exile in present-day Rajasthan as the Capital witnessed horrific violence. This verse describes that disorienting sensation upon being displaced from one’s home, something many can relate to as migrants today, says Hoskote, who named the book after this couplet.

Ranjit Hoskote’s translated collection comes out on August 22. Pic/Teju Cole

Ranjit Hoskote’s translated collection comes out on August 22. Pic/Teju Cole

Mir was a prolific poet, composing 1,916 ghazals and 13,585 couplets. Selecting excerpts from such a vast repertoire and maintaining the essence of the original poetry was made all the more challenging because of the very nature of the writing. “In ghazals, successive couplets are held together by the end rhyme or the refrain, but don’t necessarily have a sequential logic. So when the first verse is recited, you know the end rhyme and there’s a wave of expectation and suspense for the listener in every successive verse. There’s a playful relationship between the poet and the audience. On the printed page, as rendered in English, the whole poem is revealed at one shot and there’s no sense of anticipation,” says Hoskote.

Instead, the book’s approach borrows from another tradition in Urdu poetry. “The she‘r or couplet is regarded as a poem in itself. The ghazal is a collection of asha’ar [the plural of she‘r]. Traditionally, lovers of poetry would maintain a bayaz or notebook, to which they committed their favourite asha‘ar. So, this is my bayaz, with 150 of Mir’s verses, to which I respond most strongly. Like every bayaz, this is an additive, open-ended project.”

Mir is credited as one of the pioneers who gave shape to Urdu, but “he called it Hindi, as in fact the term Urdu came into use much later, by the 1780s. It was the language of the everyday at that time, and included elements of Braj, Khari Boli and Persian. By the time we get to Ghalib [in the 19th century], it was much more Persian-ised”, says the author.

Ironically, despite Mir adopting the more informal form of the language, he was eclipsed by Ghalib in mainstream consciousness. This, perhaps, is because Ghalib was in the next generation of poets in a more modern world—he went on to see his work in published form and had even been photographed. “In contrast, Mir missed print modernity by one year. He died in 1810, and the first printed edition of his works came out in 1811. There are no photographs of him either. So, Mir seems to us to be more distant in time. In truth, though, he was radically ‘modern’ in his sensibility. In chronological terms, remember that he was not very distant from us. He was a contemporary of the Romantics such as [English poet William] Wordsworth and [German writer Friedrich] Schiller,” says Hoskote, who was introduced to Mir through Ghalib. “Ghalib recognised no equals, but it was only of Mir that he wrote: ‘Mīr ke she‘r kā ahvāl kahūñ kyā Ghālib/ jis kā divān kam az gulshan-e Kashmīr nahīñ [Ghalib, what can I say about Mir’s poetry?/His collected works rival a garden in Kashmir],” he recalls.

In the decade since Hoskote started reading Mir’s poetry, the 18th-century poet has now become a familiar figure in his mind. “I have grown to feel quite close to him.”

It is perhaps ironic that Mir’s poetry, which comes from a time when Urdu was just being shaped in the subcontinent, is now being published in a time when the language is dying in India. In the introduction to the book, Hoskote writes: “To read Mir’s poems today is to defy the communitarian ideologies that have speciously splintered the Hindavi continuum into a supposedly Hindu Hindi and a supposedly Muslim Urdu.”

He tells mid-day, “Today’s dominant communal ideology perpetuates a colonial falsehood. It claims that Urdu is a foreign language. This is nonsense. Urdu originated here... There is also a persistent effort to portray Urdu as a ‘Muslim language’... Any number of major Hindi writers have been Muslim, whether Malik Muhammad Jayasi in Awadhi or Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan in Braj, or Asghar Wajahat today. And any number of major Urdu poets have been Hindu, such as Brij Narayan Chakbast and Firaq Gorakhpuri. For that matter, Gulzar sahab, one of our most acclaimed living poets, is an Urdu poet born to a Sikh family. We must oppose and reject the communalisation of history and language.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!