A ruling by the Kerala High Court in favour of a PIL filed by Women in Cinema Collective has asked the Malayalam film industry to toe the line and constitute ICCs. Why did it take so long to demand a fair and safe workplace

Pic/Getty Images

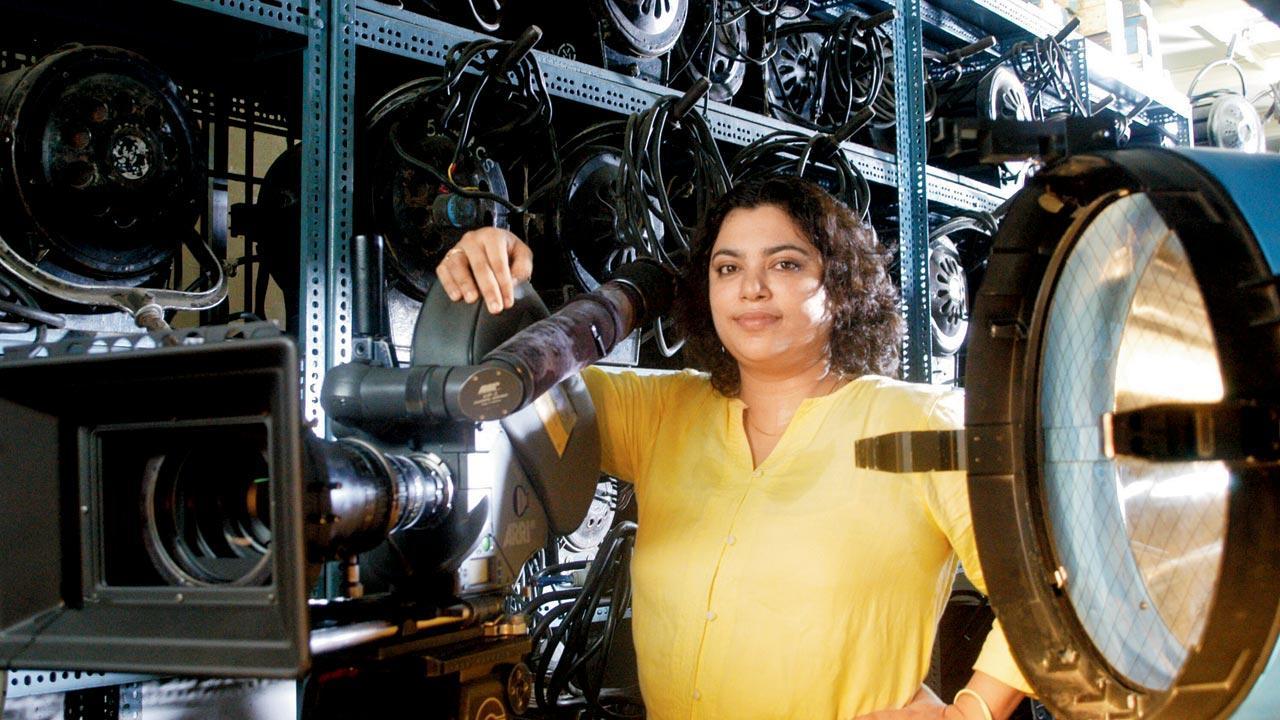

Image caption: Fowzia Fathima is the first woman cinematographer in the South who shot to fame with Revathy’s Mitr, My Friend. Director of short film Infected, which screened at Busan International Film Festival, Fathima is also a part of Indian Women Cinematographers Collective, a forum by and for craftswomen/technicians of the film industry. Actor Revathy and Script Lab Mentor Meenakshi Shedde believe that hiring more women across the board will also lead to a better environment on film sets as well as bring newer perspectives

ADVERTISEMENT

After a relentless battle that lasted five years, the Women in Cinema Collective (WCC) finally made a giant leap in their fight against the misogynist system that prevails in the film industry, particularly the Malayalam cinema. On March 17, in response to a PIL filed by WCC, the court directed Malayalam film production houses and organisations like Association of Malayalam Movie Artistes (AMMA), Film Employees Federation of Kerala (FEFKA), Kerala Film Chamber of Commerce among others to constitute Internal Complaints Committees (ICCs), as mandated under the Protection of Women from Sexual Harassment (PoSH) Act, 2013.

The collective was formed in response to events that transpired following the abduction and sexual assault of actor-survivor Bhavana Menon by a group of men in 2017. Prominent Malayalam actor Dileep was allegedly behind the crime. The matter is subjudice.

Members and allies of Women in Cinema Collective, which was formed in 2017, following the assault on actor Bhavana Menon. Pics/Instagram

Members and allies of Women in Cinema Collective, which was formed in 2017, following the assault on actor Bhavana Menon. Pics/Instagram

“While we are called an ‘industry’, the film sets are not recognised as a workplace, which was one of the major problems we encountered while trying to implement the PoSH Act. Now the court has taken cognisance and made an effort to understand the complex aspect of showbiz. It has defined film sets as a workplace with the producer being the point of responsibility, considering the way a film is structured,” shares Padmapriya Janakiraman, actor and founding member of the WCC.

Janakiraman says their issue with AMMA was that even when the body was amending the by-laws to constitute the ICC after coming under media scrutiny, the association always perceived it as a complaints committee that will be accountable to them. “ICC is an internal cell to prevent and prohibit any sexual harassment at workplace; it has the power of a lower court and can penalise and reprimand members. It has no accountability to AMMA and this shifts the power balance,” she adds, over a telephonic call from Pune.

In February 2017, Malayalam actor Bhavana Menon was abducted and sexually assaulted by a group of men. Malayalam actor Dileep was allegedly behind the incident. Soon after, Menon withdrew from the industry for five years. Earlier this month, she came out and identified herself as the survivor in the case

In February 2017, Malayalam actor Bhavana Menon was abducted and sexually assaulted by a group of men. Malayalam actor Dileep was allegedly behind the incident. Soon after, Menon withdrew from the industry for five years. Earlier this month, she came out and identified herself as the survivor in the case

Senior actor and filmmaker Revathy, who is also an integral member of the WCC, says that the court’s verdict has reached associations and film bodies in the Malayalam film industry in a “strong manner”. She, however, feels that the bigger battle is making women, particularly from the previous generation, realise that it is important to demand fair treatment. “The younger generation are taking all sorts of harassment seriously and are willing to speak up about it and move forward in a very dignified manner. But, there are a lot of women who wondered and asked us why we couldn’t keep quiet and not create an issue. We were seen as trouble. I don’t understand why making a workplace safe was considered so bad. It’s a problem when women themselves don’t take harassment seriously,” says Revathy, adding that the next step is to have the right people on the panel and ensure that they are well trained. “When somebody says ‘no’, it means no for a specific advance. I know that in our industry this ‘no’ may also mean ‘no work’ and there is a lot at stake. It will take time, but this is the first step,” adds Revathy.

In Bollywood, the situation is much better, assures actor and filmmaker Renuka Shahane. “After the #MeToo movement, every association like CINTAA [Cine and TV Artistes Association], IMPPA [Indian Motion Picture Producers’ Association] and CCMAA [Cine Costume Make-up Artistes and Hair Dressers Association] constituted an ICC. About 85 per cent production houses now have this committee in place,” says Shahane, who herself is on the ICC panel of CINTAA. “When it was constituted four years ago, we underwent training by PoSH lawyers. Often, women themselves don’t know what constitutes harassment because it can be of subtle nature.” Another body in Mumbai, Producers Guild of India, also formed an ICC three years ago. “The guild held a meeting in November 2018 where a resolution was unanimously passed to amend the by-laws and make it mandatory for all members to comply with the PoSH regulations and constitute the ICC, if they had more than 10 employees. Subsequently, declarations were furnished by all such members confirming that they had set up the ICCs. In addition, sensitisation workshops were held to educate members and handbooks were prepared to spread awareness about the regulations,” shares Nitin Tej Ahuja, CEO, Producers Guild of India.

Padmapriya Janakiraman, founding member of the WCC, says that Kerala High Court’s directive to all production houses and AMMA to constitute ICC as mandated under the PoSH Act is a giant step in creating a safer space for women

Padmapriya Janakiraman, founding member of the WCC, says that Kerala High Court’s directive to all production houses and AMMA to constitute ICC as mandated under the PoSH Act is a giant step in creating a safer space for women

Revathy admits that the scenario is better in Mumbai. “Film bodies in Mumbai have constituted ICCs without any fight. It is so comfortable here because people understand the seriousness of the #MeToo movement. It takes a lot of courage to say ‘yes, I am harassed’. In Kerala, we had to fight because they were refusing to follow the law of the land. Sadly, this is the reality in a state with 100 per cent literacy.”

New-age production companies are taking sexual harassment seriously. “On the first day of Tribhanga [Shahane’s debut Hindi directorial for Netflix], a person from Netflix did a 45-minute talk about what constitutes harassment. The conversation was in Hindi and a lot of questions were asked. Ideally, one has to inform their head in case of sexual harassment, but what if the head is the perpetrator or the ICC doesn’t take your complaint seriously. In that case, we were told that there is a website where we can register a complaint anonymously,” shares Shahane, adding that things have changed drastically from the time when she made her debut in industry as actor. “Back then, we would be extra careful, especially when we had to go for an outdoor shoot. We would warn each other,” she recalls.

Meenakshi Shedde, Ajinkya Chikte, Chetan, Renuka Shahane and Revathy

Meenakshi Shedde, Ajinkya Chikte, Chetan, Renuka Shahane and Revathy

Meenakshi Shedde, India and South Asia Delegate to the Berlin International Film Festival, independent film festival curator, and Script Lab Mentor, says, “In addition to the law acting as a deterrent, establishing that you can’t get away [after molesting somebody] and that there will be consequences to your action, the other solution is incentive-based, where women are empowered and women-led films are funded. When we see women, especially in the capacity of producers, directors and technical crew, calling the shots, the environment will change. It also percolates to the micro level, from how a scene is shot, what is being said, how it is being said, to the gaze from which the film is seen.”

Janakiraman suggests auditing can be a good step forward. “There should be a criminal registry of every person who is employed on a film set, even if it is a temporary job. Additionally, since most films need a certificate from the Censor Board for their release, perhaps the board can ask for a certificate stating that workers employed by the producer were not involved in any criminal cases, as demanded by every corporation in the country.”

And what do the men think about this? Kannada film actor Chetan, who founded Film Industry for Rights and Equality (FIRE) in 2017, which works to tackle sexual harassment at workplace, has strong reservations about allowing production companies and cinema-related bodies to self-regulate. “I am not sure to what extent the misogynist mindsets that are at the helm of most bodies in the Kannada film industry would be able to follow the law in the right spirit,” shares Chetan, 39, adding, it would be far useful to have one overarching body that has a team of experts and reputed people from the industry on board that everyone can reach out to, in case of any misconduct.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!