Christmas comes as it has for more than a century in one of the last remaining examples of community living—dormitories for Catholic men who come to the city to work. And sometimes can’t go back home for the season. Kudds are in their sunset years, but the spirit of community and faith at their foundation lives on

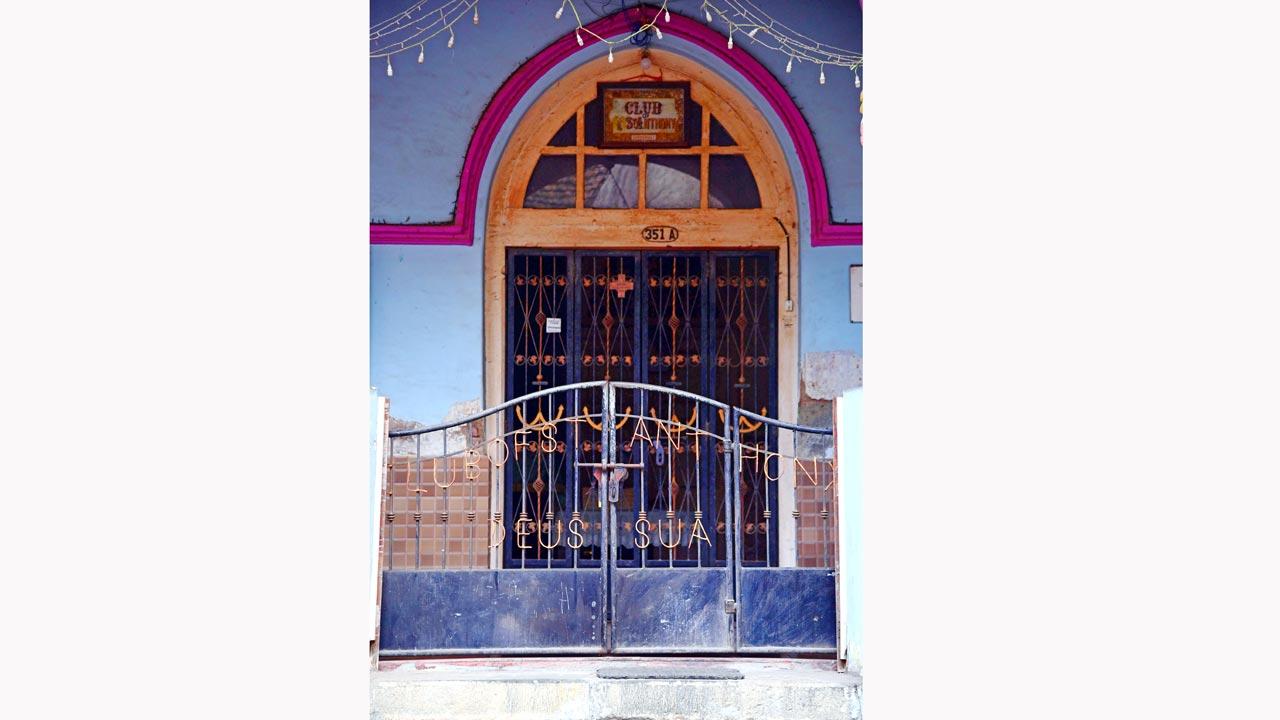

The ornate blue and pink exterior of the Club Of St Anthony (Deussua), which boasts 3,000 members. Pic/Shadab Khan

What does home mean to someone living in a city 500 km away from family? For the 12 inhabitants of 198A, Doctor Viegas Street, it is the sight of their nine-year-old yellow Labrador Bruno sleeping under the glow of Christmas lights. In the days leading up to the festival, they’re preparing to return to their native Sawantwadi but that has not stopped them from excitedly decking a tree with sparkling ornaments and putting together a simple crib.

ADVERTISEMENT

Henry, 40 and Maxi, 62 —both Dsouzas—welcome mid-day into the 117-year-old Savantvadker’s Head Club, a communal dormitory for men from the Sindhudurg town. As we flip through the institution’s register, the first entries in the frayed and delicate pages date back to 1906—when the rent was R12. A bygone era of Mumbai’s housing and urbanity unravels.

Goan counterparts of this club, called kudds, once beckoned thousands of young men from the sunshine state, sheltering them as they looked for jobs as shippies (workers on merchant and cruise ships); or at the city’s docks and mills; as cooks in the homes of the elite; and as hospitality staff. These shared living spaces in neighbourhoods such as Kalbadevi, Dockyard Road, Girgaum, and Matharpacady were known for their economic and unchanging rents.

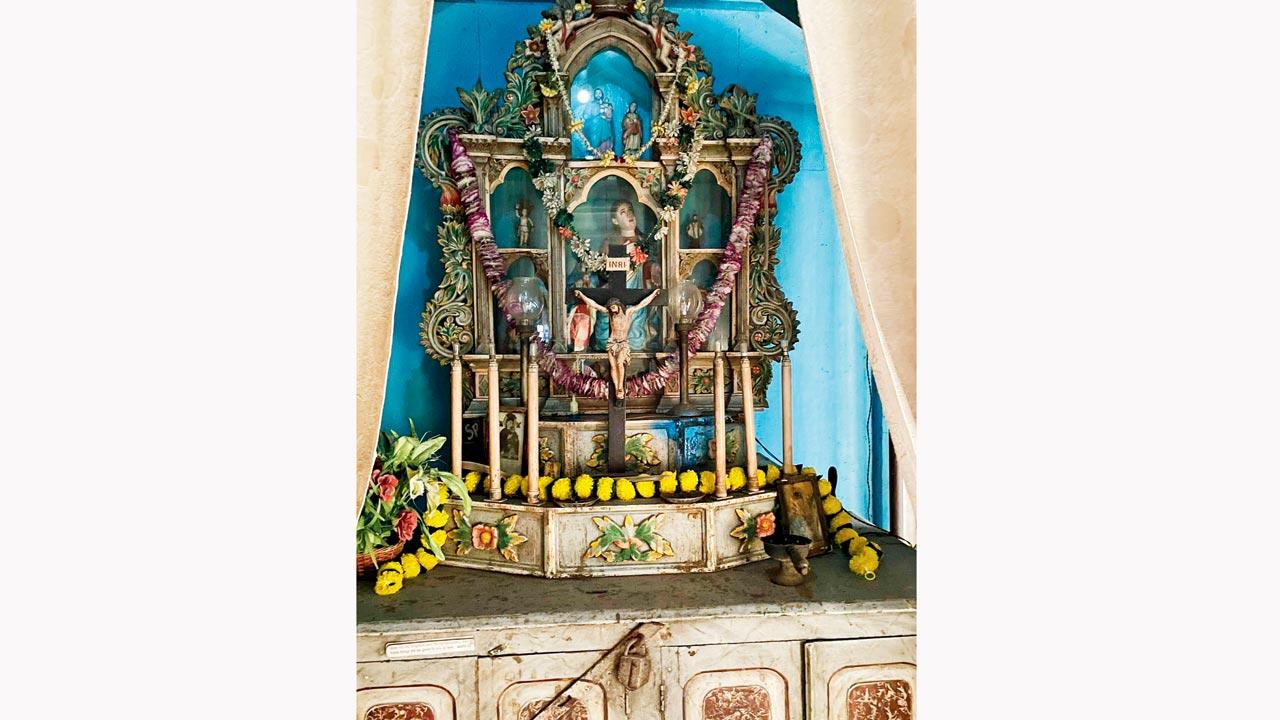

Lore about them features deep descriptions of pots of spicy fish curry, lines of trunks piled up against the walls, and strict rules about prayer and sleep times. Large, ornate altars are given pride of place. Come Christmas, the festoons and baubles used to decorate the kudds are all put up in the vicinity of the altars, some of which are home to century-old idols placed when the clubs were first established.

Kalbadevi’s Jer Mahal has been home to Goan kudds for a century. Pic Courtesy/Shruti Railkar

Kalbadevi’s Jer Mahal has been home to Goan kudds for a century. Pic Courtesy/Shruti Railkar

At the year’s end, circumstance—or, less frequently, choice—would compel some residents to stay put in Mumbai. But festivities were far from bleak. Dr Aida Dourado, a Goan professor whose PhD maps Mumbai’s kudds and Goan migrants, says that in the past, Christmas Balls were keenly looked forward to. “We met up with our friends in Dhobi Talao and set off for Byculla, Dadar, and the church grounds in Bandra where dances would be held on Christmas Eve,” says Rony Fernandes, who once lived in Dhobi Talao’s Velim club. Meanwhile Maxi Dsouza, who has lived at the Milagris club for 40 years, recalls decade-old memories of evenings spent cooking karanjis and carolling in the streets of Cavel and Chira Bazaar.

Christmas and Easter aside, Feast days at each club—to honour their patron saint—are momentous reminders of home and one’s parish. “During times of festivity, traditional dishes like vindaloo, sorpotel and sannas, as well as snacks like doce de grão, find a place in the menu. Kudd residents tend to be very pious people… If, for example, one of the residents gets a job, they will organise a prayer service that will be attended by the rest,” Dourado adds.

A No Footprints tour, featuring a Matharpacady kudd, in progress

A No Footprints tour, featuring a Matharpacady kudd, in progress

Harshvardhan Tanwar, co-founder of No Footprints which organises guided tours of kudds in Matharpacady, highlights how intrinsic clubs are to the metropolis’ heritage. The first ones were established at the start of the 20th century. “The kudd system fostered a kind of community living that’s gradually ending. Community spaces of the past are now being gentrified. They may be the last example of housing where migrants could come together and claim space for themselves,” Tanwar explains.

Each club was set up to serve migrants from a particular town or village. Their significance to the city’s labour force and economy inextricably tied them to the identity of buildings they were housed in, such as Jer Mahal. When men like 56-year-old Mario Lobo, of Goa’s Aldona, first walked into a kudd near Kalbadevi’s Edward Cinema in the 1980s, these communal living arrangements had already existed for a century.

Harshvardhan Tanwar, Co-founder, No Footprints

Harshvardhan Tanwar, Co-founder, No Footprints

As they did then, the Goan and Sawantwadi clubs ring in the festive season amid questions about their value in a changed city. The number of residents is dwindling, and the conditions of some dormitories suffer as upkeep remains a challenge. Yet, nothing seems to chip away at the sense of community that is at their very foundation.

It is their severe, austere look that makes these clubs instantly recognisable. As Henry Dsouza gives us a tour of the Milagris club, he points to a room on the second floor where as many as 10 people used to sleep. To this day, residents of many such clubs sleep on mats placed on the floor, or on the trunks used to store their belongings. Rony Fernandes, a man in his 60s, recalls, “Before they were fashioned out of metal, these petts were made of wood.”

Henry Dsouza, who has been a member of the Milagris club for 13 years, feels a sense of commitment and duty to it and his fellow residents. Pic/Atul Kamble

Henry Dsouza, who has been a member of the Milagris club for 13 years, feels a sense of commitment and duty to it and his fellow residents. Pic/Atul Kamble

The common perception of these dormitories is that they are spaces defined by strict regulations—about sleep times, prayer and cleanliness. While cleanliness and hygiene is still a mandate, many clubs have relaxed rules about wake up times and saying the Rosary together. Nonetheless, many members continue to feel a sense of accountability towards their second home.

Henry Fernandes can still recall the traditional dishes prepared lovingly for Christmas. Now in his late 70s, he serves as the treasurer of the Federation of Goan Clubs (Kudds), but was once resident of Jer Mahal’s Club of Ponda. For men like Fernandes, living in a kudd was an education in domestic duties such as cooking—duties which all residents were expected to fulfil. “Whether you are rich or poor, you are treated the same in our club—the rules are the same for everyone,” says Henry Dsouza, who has lived at the Milagris club for 13 years.

A resident of Jer Mahal’s Majorda kudd stands at a balcony lit up for Christmas 2023. Pic Courtesy/Aida Dourado

A resident of Jer Mahal’s Majorda kudd stands at a balcony lit up for Christmas 2023. Pic Courtesy/Aida Dourado

Unlike hostels or dormitories meant for the youth or working professionals, these clubs needed no introduction or advertising. Across generations, Catholic men from Goa and Sawantwadi have known that if life brings them to Mumbai’s shores, they can find a roof above their heads alongside familiar faces—from their parish, village or school. “New residents were given a few months to find a job… In the two years I spent in Dhobi Talao, about 25 to 40 men lived in the club at any point in time. And everyone helped each other, especially if someone was short on money. No one ever went hungry,” says Rony Fernandes, Mumbai Vice President of the Federation.

Among former residents, there’s a palpable, sentimental attachment; for many, these spaces were essential pit-stops to eventual success and prosperity. Antonio, Trustee of the Club of St Anthony at Dockyard Road, says that seven people may live at the club now, but its members are 3,000 strong—including expats in the US and Australia. At one point in time, they even had their own football team. “These members come back each year to pay their rent (priced at Rs 50 per month), or even to spend a night or two,” he says. Fittingly, the Christmas spirit of giving is a year-long phenomenon here. At Chira Bazaar’s Milagris, past tenants donate funds towards its upkeep and longevity, so generations of men after them can continue to have a sense of security in a city that is known to be unkind and exacting.

Altars have a central presence in kudds and often house century-old idols. Pic Courtesy/Rony Fernandes

Altars have a central presence in kudds and often house century-old idols. Pic Courtesy/Rony Fernandes

This is also the spirit that drives the work put in by the Federation, which supports Goan clubs and looks into their concerns. Mario Lobo, its Secretary, conducted a city-wide survey of Goan clubs to find that while more than a hundred exist, a few more than 50 are truly functional and utilised. This has much to do with the changing careers of the kudds’ main takers: Employees of merchant ships and cruises now board from Goa itself, while those with ambitions to work in the Gulf or North America no longer need to board flights from Mumbai or undergo medical tests here.

“Mumbai is no longer an in-between destination for them,” says Federation President Thomas Sequeira. A former banker and Mumbaikar who now splits his time between Goa and Canada, he often issues clarifications to people who worry that certain clubs have been shut. “The kudds we see today are the result of work put in by Goan ancestors… It’s important to remember the two reasons why they were established: Dwelling and benevolence. The latter is to ensure that support can be extended to a member’s family after he passes away,” says Sequeira, adding that the clubs are still essential for Goans, especially those who are less privileged.

Even in a Sawantwadi club such as Milagris, residents who have spent decades walking up its narrow staircase and slept on its stone floors, feel a sense of deference to the space. “If it weren’t for this club, many of us would not have come to Mumbai in the first place,” says Maxi Dsouza. “When we pray the Rosary together, we make sure to thank the men who set it up. We owe them a great deal.”

Rs 12

Monthly rent paid by the very first occupants of Savantvadker’s Head Club, in 1906

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!