Creator-writer duo Niren Bhatt and Amar Kaushik talk about bringing the peepul-haunting juvenile ghost from the Konkan belt into a mainstream comedy-horror film

Sod Munja is a ceremony, usually performed as part of marriage rituals, signifying the end of the student phase and the beginning of the Grihastha phase. If a man dies unmarried before his Sod Munja, he becomes a Munjya—a spirit who resides in peepal trees or near wells

A popular folk story from the interiors of the Konkan coast has made its way to a popular Bollywood horror franchise. Writer Niren Bhatt and director-writer Amar Kaushik, who made Stree 2 and Bhediya, decided to fashion a folklore into a classic horror comedy—a medium they ace. And thus, Munjya came into being.

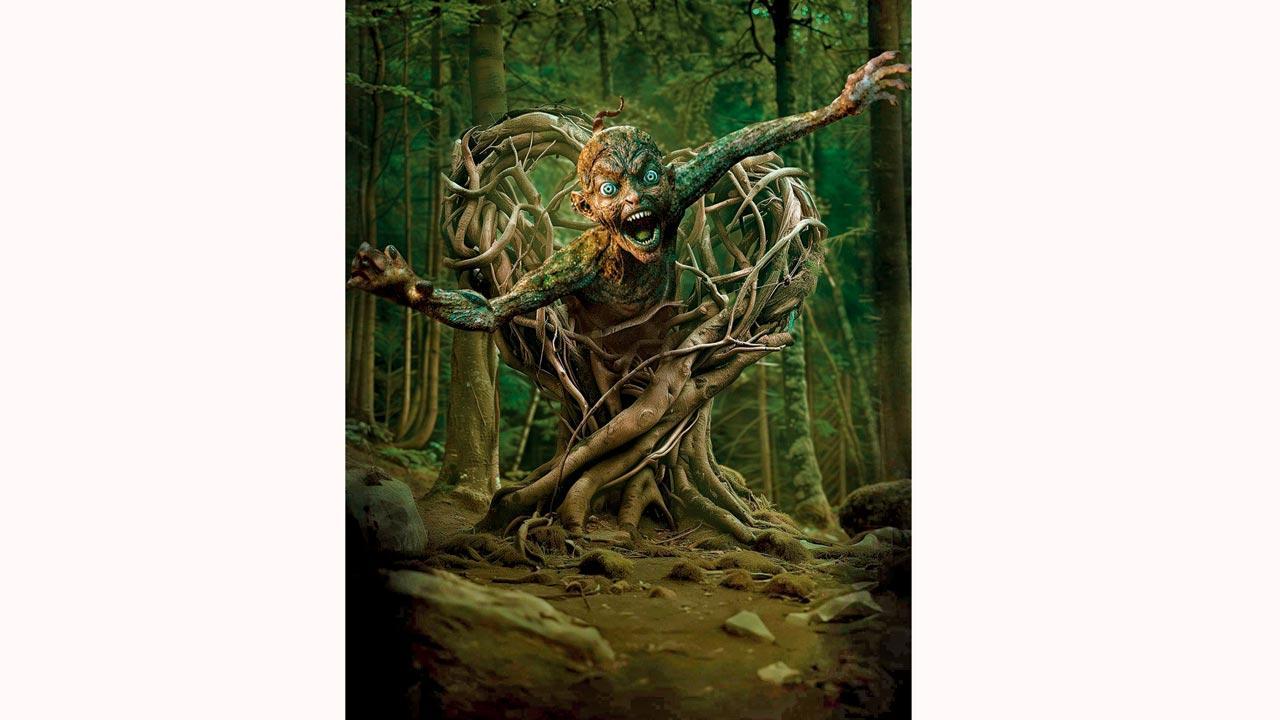

In the teaser this week, the makers introduced the first CGI actor of India, named Munjya.

Bhatt tells us that the story first came into their lives because of Yogesh Chandekar, who brought to the production house, Maddock Films, a legend from his part of the world. “In a man’s life, there are traditionally considered to be four stages: Brahmacharya (student), Grihastha (householder), Vanaprastha (retirement, originally involving leaving the city to live in a forest), and Sannyasa (renunciation). The Upanayan or Thread Ceremony, known as Munja in Marathi, marks the initiation of a child into the student phase. Sod Munja is another ceremony, usually performed as part of marriage rituals, signifying the end of the student phase and the beginning of the Grihastha phase. If a man dies unmarried after his munja has been performed but before his Sod Munja, he becomes a Munjya: A spirit who resides in peepal trees or near wells. The Marathi expression ‘Baaraa pimpla varcha munjya’ refers to someone with a restless spirit, akin to moving from one peepal tree to another,” Bhatt explains.

Niren Bhatt, co-writer; (right) Amar Kaushik, scriptwriter

Niren Bhatt, co-writer; (right) Amar Kaushik, scriptwriter

A practical explanation for this belief is that peepal trees, with their large canopies, release significant amounts of carbon dioxide after dark. The fear of munjya likely discouraged people from sitting under them after sunset. But where’s the mystery and lore in sciences or logic?

Bhatt and Kaushik developed the story over three years, and for research, visited several wadas and orchards around Dapoli and Ganpatipule where Munjas have been ‘tied down’. “Everyone has a munjya story but has never actually met a munjya,” Bhatt explains. “Kissi ke sarr pe baith gaya; kissi ko pathar se maara. A ceremony is conducted to control the bal rakshas. He is a monster but a child because he died young. He bothers people to fulfill his desires, and usually wants to get married. Munjyas aren’t typically malicious; just juvenile, petty nuisance. They really seem to like pelting stones at those standing underneath trees.”In their story, the munjya somehow breaks free of the peepal tree and wreaks havoc.

At this point, Kaushik who was in a shoot, steps in. We ask whether three years of reading and researching ghosts and spirits plays on their mind. “Sometimes,” Kaushik says, “during the writing process, we wondered whether munjya visited in our dreams. Our films are made out of our nightmares; whenever we are writing, we are perpetually scared. If someone overhears conversations from the writers’ rooms, they’ll think we’re tantrics. A lot of it we carry home and it does play on our minds because Niren reads some 10 books. We then dissect and go watch YouTube videos on real stories of such incidents. By the end of it we have a mix of bizarre, boring and cinematic. The funny stories however come from the locals, when we go on recce. Most of it is not written anywhere. What we forget is that when it comes to ghosts, everyone has a story and it is not scary in itself but in how it is told. Sometimes at the end of a long writing session, we go through our own material and wonder, What on earth are we writing? But ‘more outrageous, more hilarious’ has worked for us.”

Such haunting folklore from varied sub-cultures is new to mainstream movies. After the success of Kantara last year, there is an increased emphasis on finding tales grandmothers narrated: Of kings and demons, and spiritual connection between humans and spirits. “If you see the movies we have worked on,” Bhatt says, “they also tell the tale of the milieu. Stree is from Chanderi; there are over 42 archaeological sites in the vicinity. So her legend is born out of that world. The architecture, the heartland tropes all indicate why such a tale would have come about. It is steeped in history. Similarly, Bhediya is from the jungles of North East. Local beliefs and ideas get woven into the film. In Munjya too, there is an attempt to weave in the subculture of the Konkan belt, their fears and beliefs make up the composite of the story we have written. The sea is a big part of the belief system.”

This affinity to tell a story authentically pushed Kaushik to pass the director’s baton to Aditya Sarpotdar, best known for his Marathi horror flick Zombivili. “You can’t make good films if you accept baggage,” Kaushik says, “There is no pressure to make you laugh. There is no pressure to send a message.We wanted to bring back nani ki kahaniyan. To remain as pure in storytelling. It’s about the story and the characters, the world and in the end, it should be entertaining. Pressure of any kind brings competition, and the minute you compete in any way, you stop being you. You are no longer unique. The beauty of this world and all the horror comedies we tell and want to tell is that they have to be unique. We look for why this legend first appeared and what makes it so popular. Legends tell you everything you have to know about the people and that society. The ghost, spirit, monster, is also a character. We treat it with much empathy: What’s his backstory? Who was he in human form? What was his state of mind when he died? What are his unfulfilled desires?”

Will Munjya and Stree have an Avengers-like reunion in the near future? “If a film works, it has the legs to be more—a sequel, a spin-off, a multiverse. We didn’t write Munjya as the male equivalent of Stree. We didn’t write Bhediya with the potential to cross wires with Stree either. But it’s a good thing that there are cross connections. The possibilities are endless,” says Kaushik.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!