How did India lose the advantage it had gained in January with a sharp drop in COVID caseload? Are we on the brink of a second wave? And why is Maharashtra always the worse hit? Mid-day looks for the answers

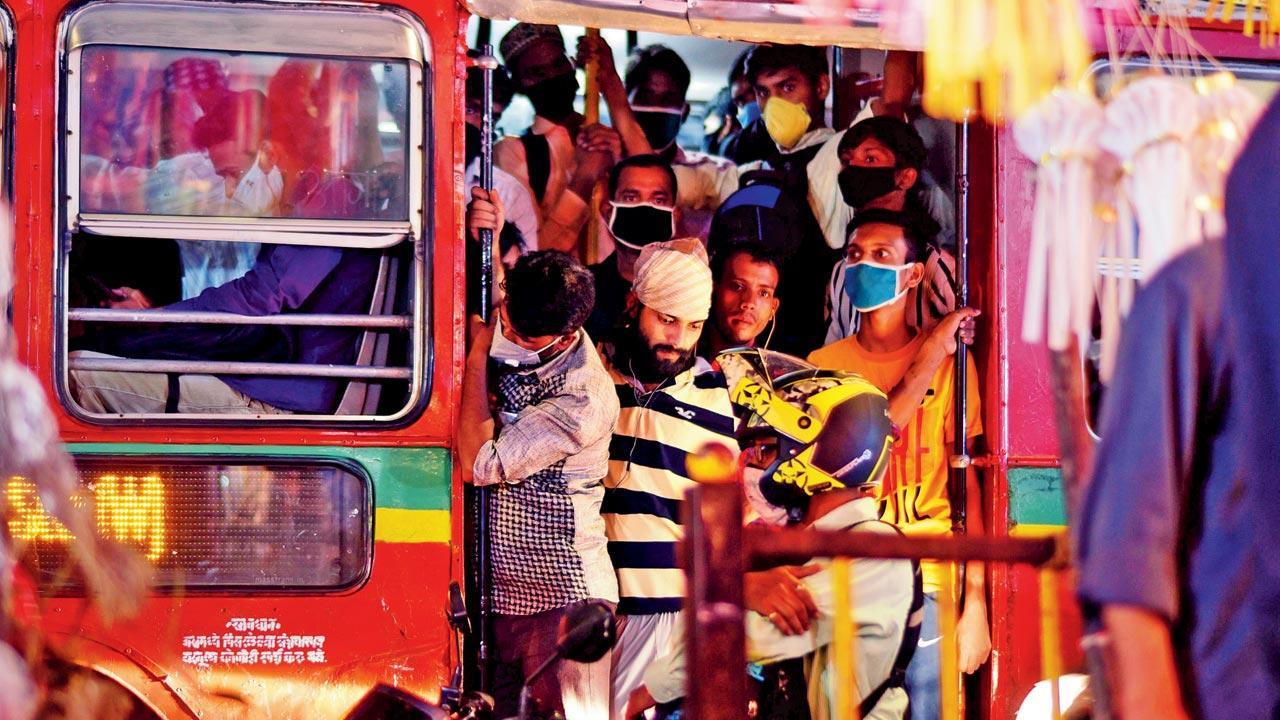

Despite the ‘no mask, no entry’ rule, commuters continue to flout COVID-19 guidelines while taking public transport in Mumbai; (top inset) receipt of fine issued by the BMC officials. Pics/Suresh Karkera

Viruses like to play games. They also behave like boomerangs, coming back at you with consistency and force after a lull. One look at the history of the deadly 1918 Spanish Flu and 2019’s Coronavirus pandemic and you know the above is true.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Spanish Flu first appeared in early March of 1918, and had all the hallmarks of a seasonal flu. But by April that same year, it had spread through Italy, Spain, England and France. From September through November, cases skyrocketed. Lasting two years, it saw three distinct waves, infecting 500 million and killing 20 to 50 million. Experts believe that the fatal severity of the Spanish Flu’s second wave was caused by a mutated virus.

Receipt of fine issued by the BMC officials

With the COVID-19 pandemic, India fared pretty well, with a comfortable January and February 2021 after peaking in September 2020, recording more than a million active cases. By the first week of February, India was barely counting an average of 10,000 COVID-19 cases per day. More than half of India’s states were not reporting even a single COVID-related death. In a drastic turn of events, a week later, India saw a spike of nearly 87,000 cases. Maharashtra, which has accounted for the bulk of India’s COVID-19 cases, is now contributing more than 50 per cent of the new cases. The fear of a second wave looms—are we in its grip already? Is this the work of a mutant virus?

It is difficult to say, thinks Dr Jay Mullerpattan, consultant pulmonologist, PD Hinduja Hospital and MRC. “Different parts of our country have had their own set of waves. Delhi has already seen three waves; in Mumbai, this is probably the beginning of the second wave. We have observed that India has trailed a few months behind in comparison to what’s unfolded in Western countries. Even in the first wave, our peak came two or three months after the US and UK. Different parts of the country will experience varied dynamics.”

Graphic/Uday Mohite

The average per million testing for COVID-19 in India is 1,62,697, which means the country is on an average conducting 1.62 lakh tests for every 10 lakh people. Is the surge due to an increase in testing then? Dr Lancelot Pinto, consultant respirologist, PD Hinduja Hospital and MRC, says, “Our hope that this isn’t a second wave comes from seroprevalence studies that suggest a significant population across the country has been already infected, and the fact that we did not see second waves post-Diwali, or after New Year’s Eve [when people met and gathered in large numbers]. However, we must remember that seroprevalence studies have not shown a uniform prevalence. For example, slums tend to have a higher prevalence than private apartments, and the virtual end of the lockdown may cause new infections, leading to a second wave. The city of Manaus, Brazil, is a case in point: they proclaimed a level of immunity that was being equated to ‘herd immunity’ last year, but experienced a shortage of oxygen during a second wave this year. It is good to be optimistic, not complacent.”

The percentage of individuals in a population that has antibodies to an infectious agent is called seroprevalence. According to a survey conducted by a team of researchers at the Banaras Hindu University (BHU), the seroprevalence frequency in 14 Indian districts, encompassing five states, varied between 0.01 and 0.48. “This suggests a high level of variability among the regions. The minimum antibody positive people were observed in Raipur district of Chhattisgarh, whereas maximum antibody positive individuals were found in Ghazipur district of Uttar Pradesh. The high prevalence of antibodies in many of the districts suggests that the soft herd immunity in India is underway,” reports the BHU paper titled, Estimation of real-infection and immunity against SARS-CoV-2 in Indian populations.

Gyaneshwar Chaubey and Dr Jay Mullerpattan

India is, therefore, not suffering from a second wave, argues the paper, which is submitted to medrxiv.org and is yet to be peer-reviewed.

Gyaneshwar Chaubey is a professor of genetics at BHU, and one of the main authors of this study. A study conducted by him and a team of top genetic experts last year revealed that the Indian genes have protected the population against the Coronavirus. In the recent study, published on February 8, Chaubey again reassures India that all is well. “At the moment, there is a rise in the number of cases in some parts of the country. However, if you look closely, it is not an exponential rise.

Dr Lancelot Pinto

Outbreaks are being reported in places where less people have got immunity against the virus. Let’s take the example of Kerala and a couple of countries that were deemed ‘model’ regions. Like Kerala, New Zealand, southern Australian or European countries like Estonia managed well in the beginning. People followed all the lockdown rules, and therefore, a majority of the population did not get infected by the virus. Immunity in the population was very low. These populations are now stepping out of homes, and therefore, most vulnerable to COVID-19. They are the ones causing the resurgence of the infection,” Chaubey explains.

The infection and death rate per million and the case fatality ratio in India remain substantially lower than many of the developed nations. Several factors have been proposed, including genetics. One important factor is that a large chunk of Indian population is asymptomatic when carrying the SARS-CoV-2 infection. Thus, the real infection in India is much higher than the reported number of cases. Therefore, the majority of people is likely to be already immune in the country, Chaubey writes in the paper.

People, not adhering to social distancing norms despite surge in COVID-19 cases, buy vegetables at an APMC market, in Solapur, in February 2021. Pic/PTI

To understand the dynamics of real infection as well as levels of immunity against SARS-CoV-2, his team performed antibody testing (serosurveillance). “The aim was to estimate the level of immunity against COVID-19 among urban street vendors. We picked vendors for our study since they tend to be the biggest carriers of the virus. They come in contact with the home-quarantined population, and therefore, we wanted to see if they have antibodies in them,” he adds.

During the months of September 2020 to December 2020, they surveyed such vendors and found out that all the participants in this study were asymptomatic; they did not know that they ever had COVID-19. “They all had antibodies in them. This suggests that the number of real infections in India is several fold higher than the

government reported cases. So, we may need to reconsider the case fatality ratio. The present case fatality ratio of India (1.44) is significantly lower than the global average (2.15). Considering our result which shows a far greater number of real infected people, the actual case fatality ratio of India could in fact be at least 17 times lower. It is therefore likely that most of the hotspots are saturated with the immune people. The chance of a second wave is highly unlikely,” the BHU paper concludes.

Students leave for their hometowns after Pune authorities announced partial restrictions citing an increase in COVID-19 cases in February 2021. Pic/PTI

But with five Indian states [Maharashtra, Rajasthan, UP, MP and Gujarat] showing a sharp rise in cases, how does team BHU’s argument hold? Can we really rule out the possibility of a second wave? “There have been relaxations in rules; more people are permitted at gatherings, and such events have been proven to be superspreaders across the world. Lockdown fatigue has also lead to individuals indulging in risky behaviour, including eating together (with the consequent lack of a mask), celebrating and crowding indoors. All these could have contributed to an increase. Once cases start piling up, the nature of spread in epidemics tends to be exponential, and measures need to be taken to flatten the exponential curve,” Dr Pinto explains.

Interestingly, this second peak was predicted last year by a group of researchers in Pune. A modeling study conducted by the Tata Consultancy Services Research (TRDCC), Pune, in collaboration with health group Prayas had said that with the level of relaxation around that time, the peak load on critical healthcare (people requiring oxygen support, ICU, ventilators, etc) can be sustained until October-end. The team developed a fine grained model and their analysis indicated that a significant number of people from Pune is still susceptible to the infection. Dr Shirish Darak, senior researcher at Prayas, says, “This is a Pune city-specific model, which basically takes into account people’s movement. It also provides what the different scenarios would be if we choose particular interventions to curb the spread of the virus in the city. What we had predicted last year itself is that if we open up schools, malls, restaurants, theatres, etc., a wave is likely to occur in March 2021. And that, more or less has come true.”

According to this study, the way the epidemic will further evolve in these places will depend on the local dynamics—such as demographic characteristics, population density, people’s mobility and migration, testing and quarantine interventions and societal compliance to preventive behaviours (mask use, social distancing, not crowding). Their model essentially created a digital twin of a particular area, in this case, a digital twin of Pune. Their predictions for last year read: “Our analysis shows that different wards are at different stages of the epidemic. By mid-August 2020, in some wards of Pune, with crowded dense localities, around 35-40 per cent were already infected. As against in some wards (eg: Kothrud, Warje, Aundh) this proportion is likely to be as low as 15 per cent. A majority of the infections is being seen to occur through household contacts. Along with that, longer interactions in enclosed and crowded places is likely to increase transmission risk (places such as banks, offices, factories, eateries).”

Dr Ritu Parchure, senior researcher at Prayas, adds, “While we believe that this wave won’t be as bad as the previous one, a lot of people can expect to be infected this time around.”

Two weeks ago, the Pune administration announced a night curfew in Pune district from 11 pm to 6 am. With a steady rise in cases in the city, the curfew has been extended till March 14.

Several factors influence whether a particular disease is seasonal in nature. Some pathogens may spread less well in greater humidity. Annual epidemics, like influenza, may occur because of climate or patterns of social mixing—often driven by the school year or people staying inside more during the winter. In this context, what are the many factors responsible for India’s current surge? Dr Pinto says that it’s clear that weather had not played a role. “There is a theory that lower humidity and lower temperatures facilitate spread of the virus, but this is a hypothesis. Social mixing has definitely increased over the past few months, and this is likely to have played a bigger role than the weather.”

So, what do the trends in diagnoses and deaths mean for the future course of the pandemic in India? “Mortality trends, as expected, lag behind infection trends by a few weeks. With an increase in the number of cases, it will be interesting to see whether there is a commensurate increase in the number of hospitalisations and more importantly, deaths. If, for example, the latter do not rise despite the former rising, we could be dealing with a milder version of the virus this time, and that is reassuring. If that isn’t the case, we will have to brace ourselves for circuit-breakers and focal lockdowns to help flatten the curve,” Dr Pinto thinks. That the vaccination drive has gained momentum in Phase 2, with private hospitals roped in and senior citizens showing little vaccine hesitancy, will help. “Strategically, if we could prioritise those who haven’t been infected with COVID-19 and are in a high-risk category, it would significantly ease the healthcare burden,” he adds.

The 1889-92 influenza outbreak had three distinct waves, which differed in their virulence. The second wave was much more severe, particularly in younger adults. On the other hand, the proportion of 1918 H1N1 influenza pandemic patients, who were severely ill or died, was much higher in the last two waves compared to the first. More recently, the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, though mild, had two distinct waves; this virus still commonly shows up in seasonal influenza outbreaks. A study of H1N1 influenza in 2009-2010 revealed that the second wave affected more older people, with underlying conditions.

So, what is the trend of transmission of the current COVID-19 pandemic in India? “Mortality wise, the elderly are more susceptible,” Dr Mullerpattan warns, hinting at one of the reasons why Maharashtra could be ahead of other Indian states in numbers. The state has a large senior population and is the most urbanised in India, two key factors in higher COVID incidence. “But as we see with the opening up of lockdown, the younger crowd is likely to go outdoors and socialise. It’s expected that the younger might get affected too,” Dr Mullerpattan warns.

He may be right. In the US, the average age of those infected is falling, complicating predictions about a death toll. What is the age group that needs to be most cautious in India right now then? “Everybody,” is Dr Mullerpattan’s simple response.

For now, the UK and the US cases are showing a slight downward trend compared to what they were in December and January. “In early March, their numbers are lower, but some countries like South Africa and Brazil are still showing a high case load. A lot of countries in Europe are announcing lockdowns again, including Sweden. The Netherlands has imposed a strict lockdown. In comparison, in Southeast Asia, the number of cases isn’t that high,” he adds.

Experts think that arguing about whether India is in the second wave could be a waste of time. According to the guidelines released by Lisa Maragakis, MD, MPH, an infectious disease specialist at the Johns Hopkins Medicine, it’s smarter if countries prepare for a spike or second wave in respective regions.

“Continue to practice COVID-19 precautions, such as physical distancing, hand-washing and mask-wearing, stay in touch with local health authorities, who can provide information if COVID-19 cases begin to increase in your city or town, make sure your household maintains two weeks’ worth of food, prescription medicines and supplies at all times [in case of a lockdown] and work with your doctor to ensure that everyone in your household, especially children, are up to date on vaccines, including this year’s flu shot,” Maragakis suggests.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!