Dr Lior Assaf talks to mid-day in an exclusive interview

Dr Lior Assaf is the first-ever Water Attache to the Embassy of Israel in India. He has an M.Sc in hydrology from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and a Ph.D from the Arava Institute for Environmental Studies. Pic/Nishad Alam

This year marks the 30th year of commencement of full diplomatic relations between Israel and India. As of December 2020, India is among 164 United Nations (UN) member states to have diplomatic ties with Israel. It was understood that in 2019 when India needed Israel’s help to save the water-parched region of Marathwada, the loyal friend stepped in. On his Mumbai visit in 2018, Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu signed an MoU with the Maharashtra government, appointing Maharashtra Jeevan Pradhikaran (MJP) and Mekorot [the national water company of Israel] to design a water grid system in Marathwada, south east Maharashtra. The Rs 10,000 crore project aims to provide water to a population of 30 million by 2050. The initiative is one of the largest non-defence projects of the Israeli government in India.

In keeping with tradition, this year, the Government of Israel has for the first time appointed a Water Attache to India. Dr Lior Assaf is not a diplomat; he has an academic background. He has an M.Sc in hydrology from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and a Ph.D from the Arava Institute for Environmental Studies. He has over 20 years of experience in groundwater hydrology, surface water hydrology, soil investigation, and environmental impact analyses for a variety of projects throughout Israel, USA and Sri Lanka.

Lovegrove pumping station treats 3 MLD wastewater. File photo

Lovegrove pumping station treats 3 MLD wastewater. File photo

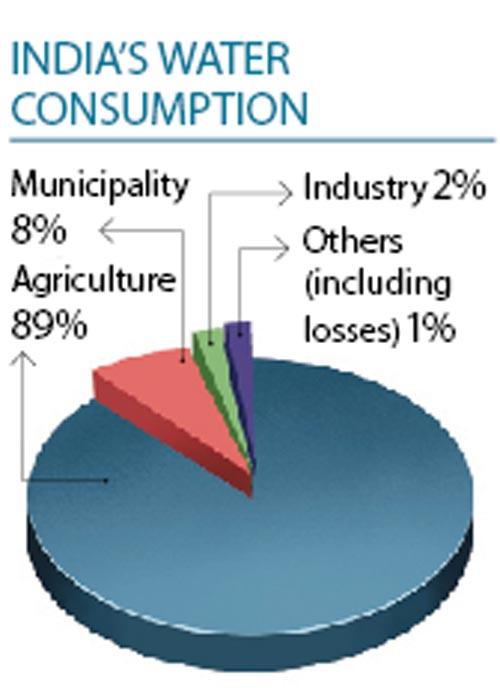

“There is no one magic approach that can solve a problem overnight. In the end, everyone has to pull up their sleeves and dive in. India already has great engineering capabilities. I haven’t come here to teach anyone anything. I want to in fact, work in cooperation with the Indian government, the local communities and stakeholders to find the right solutions,” he clarifies during a video interview, as he begins to tell us about his new position as Water Attache to the Embassy of Israel in India. “Indian agriculture accounts for 90 per cent of water use due to fasttrack ground water depletion and poor irrigation systems. Climate change has become India’s great enemy. While its effects are seen world over, in India specifically, it has hit its water resources. The government needs to rope in advanced technology to reduce the use of water in agriculture.”

He, however, feels Mumbai is performing way better in managing its water resources. Along with the Observer Research Foundation, BSE Institute and the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation’s hydraulic department, Dr Assaf has helped identify the water management issues faced by Mumbai. “I went on a recce of a water treatment plant in Mumbai and was thoroughly impressed. The city certainly has high standard water treatment facilities [with a treatment capacity of 4,000 MLD]. A project in Bhandup set up by the municipal corporation is the biggest water treatment plant in Asia. The city is blessed with good technical and engineering staff too,” he says, adding though that there is always room for improvement. “The city has a very low rate of reusing sewage water. Israel leads the world in reusing waste water. Nearly 90 per cent of wastewater in Israel is treated for reuse, most of it for agricultural irrigation. In Mumbai, sewage plants send their effluents to the sea. There is also limited use of groundwater and desalination as additional water supply sources. In the coastal areas of Maharashtra, groundwater suffers from contamination due to seawater intrusion.”

Water utilisation in different sectors in India. Map/Uday Mohite

Interestingly in Israel, some 585 million m3 of water per year is desalinated [the process of removing salt from seawater]. “Groundwater can be cleaned and treated properly for reuse. The government of Maharashtra needs to build a rigid approach for water management,” he adds. With over 60 per cent of its territory being desert and another 20 per cent semi-arid, Israel was staring at a severe water crisis in the 1930s. The nation’s leaders David Ben-Gurion and Levi Eshkol launched Mekorot in 1937. The company was tasked with transferring water from the Sea of Galilee in the north of the country to the highly populated arid south, through a water grid. Today, Mekorot supplies 1.5 billion cubic meters of water in an average year—70 per cent of Israel’s entire water supply and 80 per cent of its drinking water. “But that model cannot be replicated in India. The weather conditions won’t allow it,” he explains.

Dr Assaf says that Israelis are trained to be more prudent with their water use—a virtue needed in India. “In Israel, every drop of water that is sitting in the water tank of your house belongs to the government. We are conditioned to close the tap when not in use, or wash the car only with one bucket, and so on. A lot of people in India view water as a commodity that must be supplied by the government. But even if it [water] falls from the sky, it comes at a price. And so, every single person must use every single drop judiciously. The government cannot do this alone; public participation is of utmost importance.”

90

Percentage of wastewater in Israel treated for reuse, most of it for agricultural irrigation

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!