Fighting isolation and illness is one thing, cravings another. Author Siddharth Dhanvant Shanghvi looks back at a year of recuperation and healing, and how eating a meal a day aided this journey

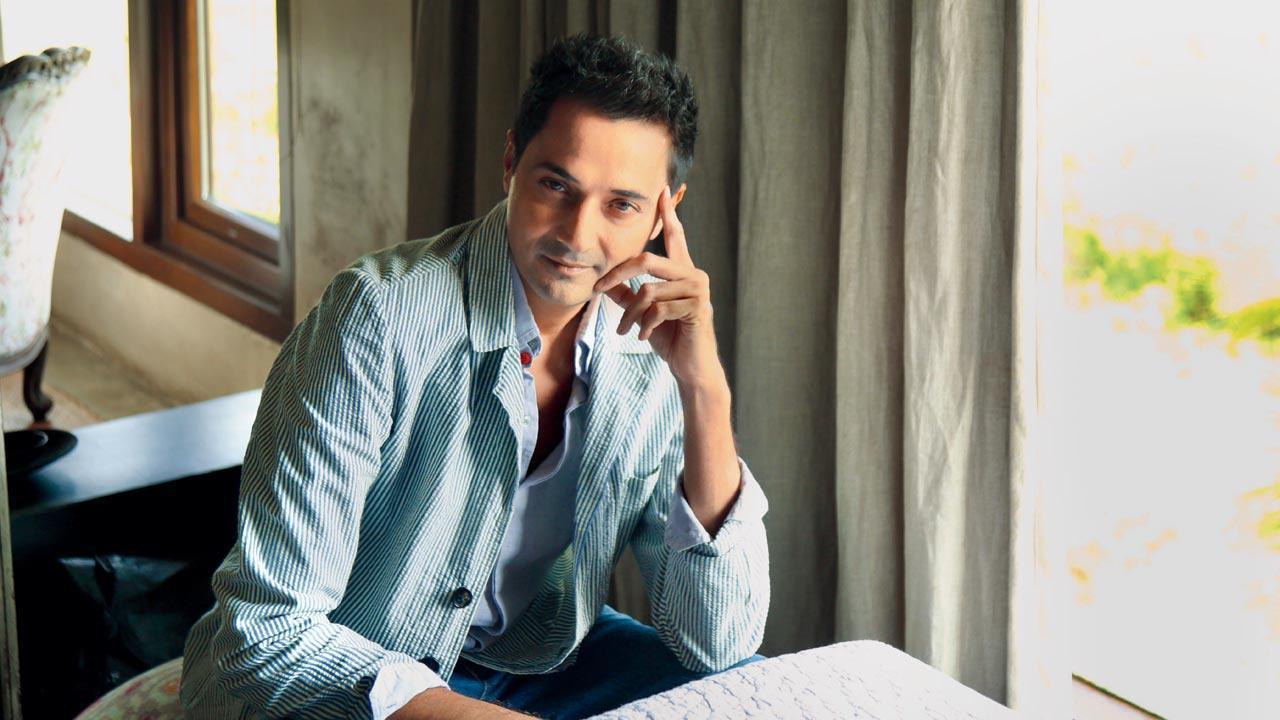

Siddharth Dhanvant Shanghvi

Last year, in the spring, I couldn’t get out of bed for a month; post COVID, a real slump, no appetite, no movement, no life. Outside my room in Matheran, where I was recuperating, birds sang—the sky an immersive blue, the forest a jewel of wisdom. Meanwhile, I felt like death. Specialists I’d met in Mumbai hospitals prescribed medicines that felt toxic, far worse than my ailment. In the peculiar, educative isolation of a long sickness—when you feel like you’re a bull in a holding pen—I knew I had to clean myself out, rinse my cells, while assessing the fraying bits.

ADVERTISEMENT

One afternoon, I lay on the forest floor, ready, finally, to submit.

Hinini hinini.

The crucial thing is the pause: make room for silence in the commotion of the struggle.

In the monsoon, I moved to Meher Baba’s ashram; the profound spiritual silence always made me feel safe, true, reflective.

There I started, after consulting with a yogi friend, on a one-month kunjal kriya programme. Following this cleanse, I moved to intermittent fasting, soon reaching my goal of eight hours of food and 16 hours of abstaining; after a few months, I switched up to one meal a day—difficult, but transformative.

In a matter of days, I felt vital, strong, alert, clear-minded, quick and taut, my body had a kind of bow string quality, vibrating with possibilities. COVID’s backlash gradually lost its violent hold over me; it was like a claw had let go. My skin shone. I tasted alcohol; but now it was poison to my tongue. I slept for four or five hours at night, I woke naturally at dawn, energetic and spry. Dawn was the right time to begin my chanting practice of namyo ho renge kyo.

But I am not writing about some diet plan; rather, I am sharing insights that come from when we change our most basic consumption patterns. Limiting food induces sharper perceptions. Hunger, invariably, makes you compassionate; while I was privileged to release myself to food, hunger is the terrible, unrelenting, painful reality that millions endure, and without choice. I now glimpsed hunger in the eyes of the porter, the waiter, the doorman—where once was a hollow, bored glint, I now saw the hunger code. Even after I had trained my body to eat once a day, I recognised hunger as a singular unifying force, more so than love, morality, or a shared passion for ideas. This made me question the idea of consumption—what you put in must also be processed and eliminated, this is work, toil, a process for body and spirit. What you consume will one day consume you.

Energy sensitivity was the most important consequence of eating one meal a day. My instincts grew sharper; my intuition a tad witchy. I spoke less—speaking was a waste to begin with. I cut out interactions that sapped my vitality. Peacefully, discreetly I eliminated people who were energy vampires (they don’t mean to be like this, they were karmically wired to absorb my life out of me. Of course, it was my job to be vigilant at the gate and of the guest). One key service we commit to life concerns the management of its energy, what you put out, what you take in, and living in admiration of what just is: prana, chi, vis vatae, that mysterious glowing matter that makes our molecules gossip ardently with each other.

One meal a day involves restraint and discipline. Hunger is violent, difficult to tame. Until my main meal at around 5 pm, I consume apple cider vinegar shots, green tea, electrolytes; by 3 pm, I’m ready to pick a fist fight for a piece of toast. But while the menu is depressing, the results are less so.

Hunger also showed me how austerity is a clarifying exercise for the soul: Less is lovely. The pandemic was a hurricane, we entered with a bunker playlist and two avocados, but we came out the other side windswept and chipped (and maybe a bit wiser for the wound). I’m so glad I had been sick, if only so I know now how much I would fight for my vitality. And I’m so lucky that in my middle-age—I will be 50 in four years—I know how to meet age: amicably, with restraint, and in prayer.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!