Urdu remains the language of poetry that accumulates aashiqs at every adaa, but Gen Z is reclaiming it as a connection to their pre-Partition heritage

Akshita Nagpal’s move from Delhi to Versova in 2023 was propelled by the success of her online Urdu courses. Pic/Nimesh Dave

Because she is the answer to our prayers,” wrote actors Deepika Padukone and Ranveer Singh on Instagram in November while revealing their newborn daughter’s name, Dua. Apt, memorable, and short—Urdu had, again, served the right word for the emotion.

It seems to be something the language is very well suited to. Never at the risk of disappearing, the interest in it ebbs and flows through its many gateways.

Cinema is at the forefront, of course. But there is also history and research, theatre and calligraphy, writing and singing; reading poetry and ghazals. And, for some, a connection to one’s roots, even three generations apart—in Punjab, Pakistan.

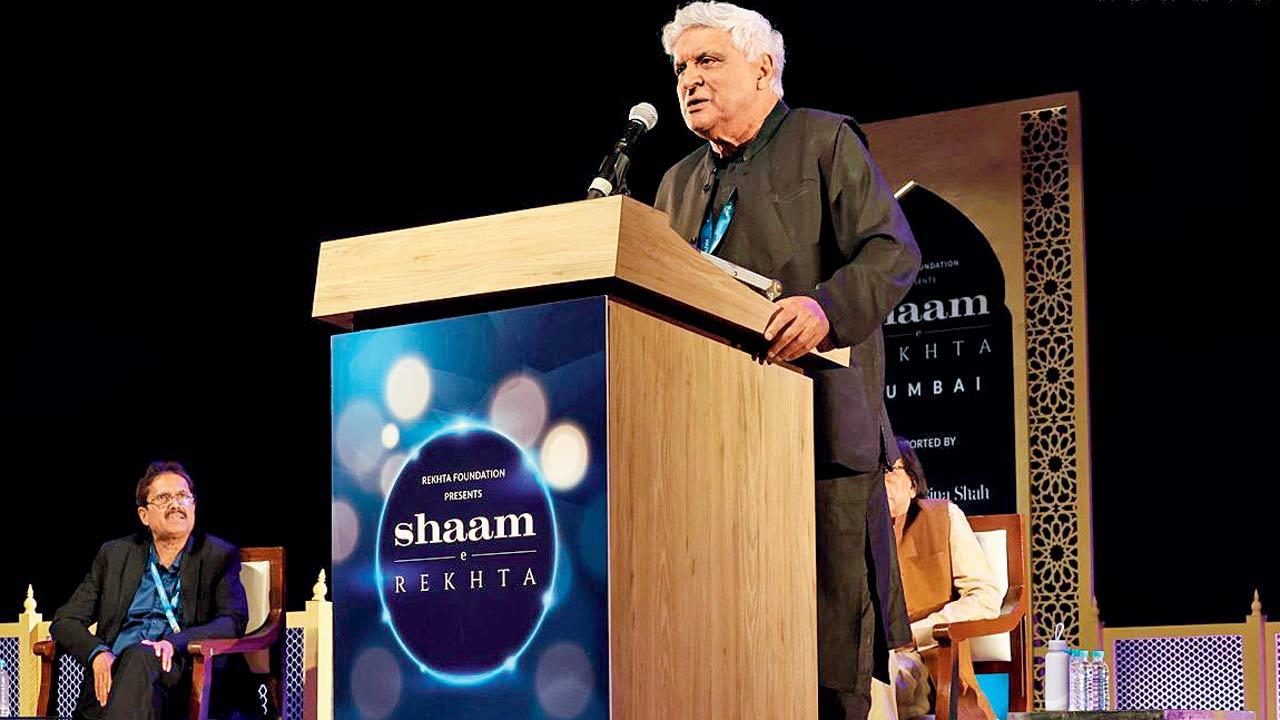

Scriptwriter and lyricist Javed Akhtar at a Rekhta event. The correspondence in Urdu between his parents Safiya and Jan Nisar Akhtar has been compiled into two volumes called Zer-e-lab

Scriptwriter and lyricist Javed Akhtar at a Rekhta event. The correspondence in Urdu between his parents Safiya and Jan Nisar Akhtar has been compiled into two volumes called Zer-e-lab

Theatre actor Ashwin Chitale says he teaches Urdu and Persian, because he’s learning the languages. “If you want to learn German,” he says, “you speak German more, don’t you?”

Based in Pune, the performer runs online classes that offer beginners’ courses in the languages, instructing in Marathi, Hindi and English. He opens other portals to the languages too, such as mehfils concentrating on philosopher Rumi or Amir Khusrau and their works, through art, and through Sufism. “Urdu is as Indian as Sanskrit, and pre-dates Hindi,” he says, “Farsi came to India with the Persians, and for official records, they adapted the script to Hindustani/Sanskrit, and Urdu was born. In fact, Urdu has many regional variants and it also seeped into Marathi in the 16th century. Words such as ‘baazaar’ and ‘sobot [to accompany]’ come from Urdu.”

The book Yaar Ki is part of Akshita Nagpal’s teaching curriculum

The book Yaar Ki is part of Akshita Nagpal’s teaching curriculum

Many of his students are language enthusiasts, but also those singing ghazals or performing on stage in Urdu who want to clean up their “talaffuz (pronunciation)”. Then there are those who practise the many forms of Urdu calligraphy, and want to know more about what they are writing.

Navin Kale, an entrepreneur and writer based in Versova, has been interested in Urdu shayyari and poetry since college. He graduated to reading and writing it, and unravelled the thread of etymology to Farsi in Chitale’s three-month course. He now burnishes his knowledge daily with the Duolingo app.

Actor Ashwin Chitale, who also teaches Persian and Urdu, performing Rumi Hai in July

Actor Ashwin Chitale, who also teaches Persian and Urdu, performing Rumi Hai in July

More than one Urdu teacher told us that most enthusiasts stumble upon the language in their teenage years, unparalleled as it is for declarations of love and lamentations of subsequent heartache. If it sticks, the love blossoms in adulthood into an interest in culture, history, literature, calligraphy and art. And that’s the kind of enthusiast most likely to be one of Rekhta’s downloaders.

The name comes from the early version of the Hindustani-Persio-Arabic-Devanagari script, and is a step to “de-stigmatise” the language and divorce it from an ascribed religion, to give its rightful place in the culture of the Indian subcontinent. The Rekhta website, and app, hosts crosswords, events, a dictionary, books, journals, and poetry. It also provides Urdu translations of “modern” books, such as the teachings of Osho.

Sanjiv Saraf, Rekhta.Org

Sanjiv Saraf, Rekhta.Org

As per its founder, Sanjiv Saraf, Chairman of Polyplex Corporation Limited, the app had 2.5 lakh downloads in 2022-23, which swelled by another 3.3 lakh in 2023-24. The website had 1.7 crore visits in 2022-23, and 2.3 crore visits in 2023-24. Their data says Rekhta.org has 1.5 lakh daily visitors and 26 lakh monthly visitors.

On ground, Rekhta holds various cultural events showcasing Urdu’s vast literary tradition, bringing on stage poets, writers and artistes, who hold audiences captive in Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Lucknow, Hyderabad and Aligarh, and other cities. “These events are platforms for dialogue, cultural exchange, and creating a deeper appreciation for the nuances of Urdu literature and art,” says Saraf, via e-mail. “We’ve seen particularly large turnouts in London and Dubai, where the South Asian diaspora has a strong presence.” Even at Rekhta, “Shayari is, of course, the centrepiece of attraction,” he adds. “We also promote other forms of arts, such as Daastaangoi, a medieval form of storytelling, and Urdu calligraphy.”

Nowhere does the lyricism of the language shine more than in Hindi cinema’s music. “Bollywood is a museum to Urdu,” says Akshita Nagpal, who moved from Delhi to Mumbai in August 2023 to run her Urdu-language courses. She has noticed a list of gatekeepers to its authenticity and usage: Lyricists Kausar Munir and Amitabh Bhattacharya are its latest champions. Munir’s grandmother, Salma Siddiqui, was part of the Urdu Progressive Writers Movement. Munir grew up in a house frequented by great writers, but formally learnt to read and write Urdu only during the pandemic under Lucknow-based teacher and poet, Abhishek Shukla. “I finally became Urdu literate to help further my understanding of Hindustani lyric-writing,” she says.

Filmmakers and writers Kabir Khan, Imtiaz Ali, Vishal Bhardwaj enlist the language for dialogue and literary references, and ensure proper pronunciation, as do Aditya Chopra and Javed Siddique (who co-wrote Dilwale Dulhainya Le Jaayenge). Singers such as Shilpa Rao, Sunidhi Chauhan, and Madhubanti Bagchi ensure good “talaffuz”, as does Shah Rukh Khan.

To Soha Batra, a Gurugram resident, Urdu is the language of her ancestors, connecting her to a land and culture she cannot reach

To Soha Batra, a Gurugram resident, Urdu is the language of her ancestors, connecting her to a land and culture she cannot reach

Nagpal started tutoring Urdu without planning to in the pandemic with 12 students, and the momentum grew to 400-plus students from the Indian subcontinent diaspora (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh) passing her Shuruaat-e-Urdu course four years on. “When I started, there was no online course in Urdu,” says the Versova resident. “This is what brought me to Bombay (sic), which is not an easy city to crack.”

In the current political climate, the work is to remind that Urdu is an Indian language, a mother tongue to many generations of Hindus displaced by the partition. To Nagpal, and her student Soha Batra, Urdu is a language to access a lost homeland and culture. Both sets of Nagpal’s grandparents came from what is now Pakistan—from Lahore and undivided Punjab. “Both my grandfathers went to Urdu-medium school and corresponded in Urdu,” she says.

“My paternal grandfather, a voracious reader, read the scriptures—Bhagvad Gita, Quran and the Bible—in Urdu. The [spoken] language was passed down to my parents; the script lost in the hustle of refugees carving a living and life post Partition.” The final days of her last living grandparent were marked with a sense of loss in more than one way. “She spoke of Lahore and Karachi, their bazaars and halwas, and I thought, the land is inaccessible and so is the language.”

And suddenly, she noticed the language was everywhere—in the names of roads, gates, statues and bus stops of Jamia Millia Islamia, where she was pursuing a Masters in Mass Communication in 2014-15. In the legends of radio and photography, such as singer-actress Begum Akhtar; in the dialogues of Mughal-E-Azam that her film-buff father spouted by heart.

“Thoda ishq-mohabbat ka bhi asar tha,” she laughs. She began teaching herself the Urdu script from self-help books bought from roadside stalls. Booksellers in Connaught Place—like Mukim bhai who ran a book-stall outside Moti Masjid—and Amrit Bookstore’s employee, Mr Momin, helped her with the script and with passionate recommendation of poetry books. There was a short course in Persian from Iran Culture House, and reading of headlines from Urdu newspapers on her daily commute.

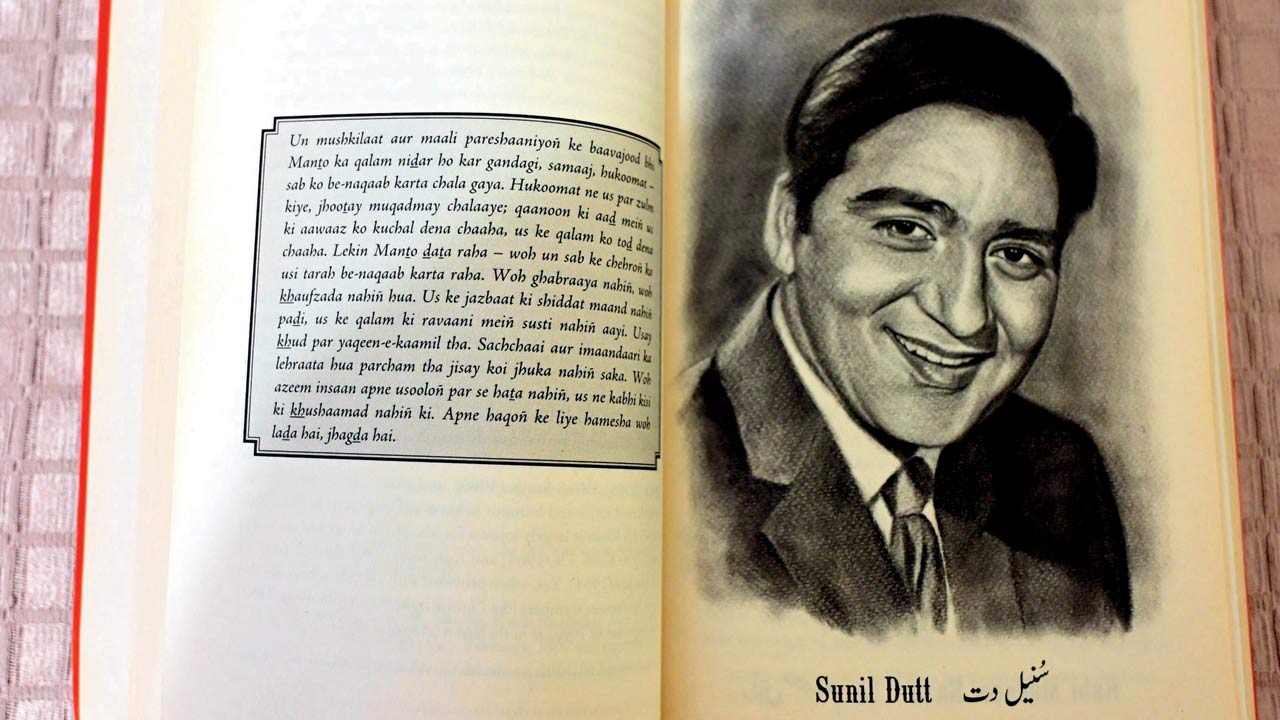

She now pours all this into her courses, which access the language through its culture. The nine to 10 classes of the foundation course promise two-line reading and writing fluency, while the short workshops of progress level courses—Taraqqi (progress) and Mashq (practise)—explore cinema, afsanche (terribly tiny tales), humour and satire. Students read letters and correspond in Urdu, which is a very vital part of literature. “We read [actor] Sunil Dutt’s to a fan and refer to Zer-e-Lab—letters by script writer Javed Akhtar’s mother, Safiya Akhtar, to his father Jan Nisar Akhtar in Mumbai over the course of their long-distance marriage,” she says. There’s Mirza Ghalib’s correspondence to his pupils, archival copies of magazines such as Shama, and standalone workshops called Filmy Zabaan which delves into Urdu nuances in the filmography of actors like SRK or Meena Kumari, as well as filmmakers and lyricists such as Sahir Ludhianvi. One of these Filmi Zabaan sessions also studied the tawaaif culture in OTT hit Heera Mandi.

But the money, as always in Mumbai, is in the movies. She tailor-makes courses for actors, singers, screenwriters to polish pronunciation. “Urdu and Hindi are Sita-Gita—twin languages,” she says, “Politicisation has made them different entities, but they share a grammar and syntax. Learning Urdu betters your Hindi.”

The education would be apparent when an actor/singer pronounces it as “harj” and not “harz”; or auqaat [status and position of a person within a timeframe]; and not “aukaad” (as we do in Bombaiyya); “Phir” not “fir” in dialogues and interviews. She also vets scripts and lyrics for this.

Rekhta.org founder Saraf says the profile of people interested in Rekhta and Urdu poetry includes “both young people, primarily aged between 18-35, and older generations who have a deeper connection with the language. There is a growing interest from millennials who turn to Rekhta for modern translations and digital content.”

And many of these are the third generation displaced by the Partition, such as Nagpal’s 20-year-old student, Batra. She is currently pursuing her English Honours from Delhi University.

“My grandparents settled in Gurugram from Mianwali district of Punjab,” Batra says, “and I saw them write in this script from right to left, and not left to right like the languages I learned in school. In Pakistan, Punjabi is written in the Shahmukhi [Perso-Arabic] script, not Gurmukhi.”

There was also the awareness that her friends inherited ancestral land, jewellery, or wedding clothes. “Like grandmother’s kangan or joda,” she says, “When I asked my grandparents, they said ‘hum toh sab loot-poot ke aaye [we have nothing; we were looted]. So languages—Urdu and Punjabi—are the only way I can reconnect to my ancestral roots and culture. Hindi is my Raj bhasha; these are my mother tongues. They connect me with my lineage, history and culture.”

Or zameen, as they say in Urdu. The connect of a person with their land is something historians Anita Anand and William Dalrymple deep-dive into in their podcast, Empire, especially the chapter on the Partition. The longing came up in most remembrances by refugees in their last days—a connection that supersedes religion, cast and cultural identity.

Batra has a hunger to read every book ever written in Urdu. To learn Persian to speak Urdu better. To visit Mianwali and Lahore. Write plays, ghazals, nazms and her own autobiography in the language of her people. “Urdu is associated with Islam,” says Batra. “But zubaan kissi mazhab ki nahin hai. Zubaan usski hai jo usse bolna chahata hai.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!