SMD follows historian and food critic Pushpesh Pant through the annals of Delhi’s history to discover what makes the food scene tick, and how food and politics are connected

India Coffee House

When food critic, historian and author Pushpesh Pant thinks about food in Delhi, a key turns on the door to some of his fondest childhood memories—sohan halwa from the city’s oldest halwai Ghantewala at Chandni Chowk, tikkis from the khomcha walas (streetside hawkers) at Connaught Place. But food is also political, especially in the national capital, and this is something which significantly preoccupies Pant. His latest book, From the King’s Table to Street Food: A Food History of Delhi (Speaking Tiger, Rs 699), kicks off with his childhood gastronomic adventures in the capital and rewinds beyond the city’s documented history (which only goes back 200 years ago).

The subsidised coffee and food at India Coffee House, or PRRM coffee house, drew not only cash-strapped students but also nation-builders and intellectuals, from MS Swaminathan to MF Husain. Pics/Getty Images

From the Mahabharata era, when the city was known as Indraprastha, Pant winds down the centuries until we reach modern-day NCR. Whether it’s cultural icons such as Ghantewala pulling down its shutters or the previously “democratically” priced eateries no longer within reach of the commoner, this version of Dilli is barely recognisable to Pant. Through it all, he discusses the influence that each of the capital’s rulers and refugee residents had on the food scene and breaks some myths about Dilli cuisine.

To begin with, he posits that there is no such thing. “Delhi doesn’t have a single cuisine to call its own. Throughout history, the city went through a lot of upheaval and every time a new ruler or dynasty arrived, and every time refugees from elsewhere in the country settled here, they brought their cultural influence,” says the historian who details this influx of cultures and cuisines in chapters devoted to Baniya, Bengali, Punjabi, Parsi, Christian, Northeastern and Bihari refugees-turned-residents. “Delhi’s food is like a sedimentary rock with many layers deposited over time. My son has another analogy for it—it’s like many layers in a falooda that you can scoop and enjoy at the same time,” he explains.

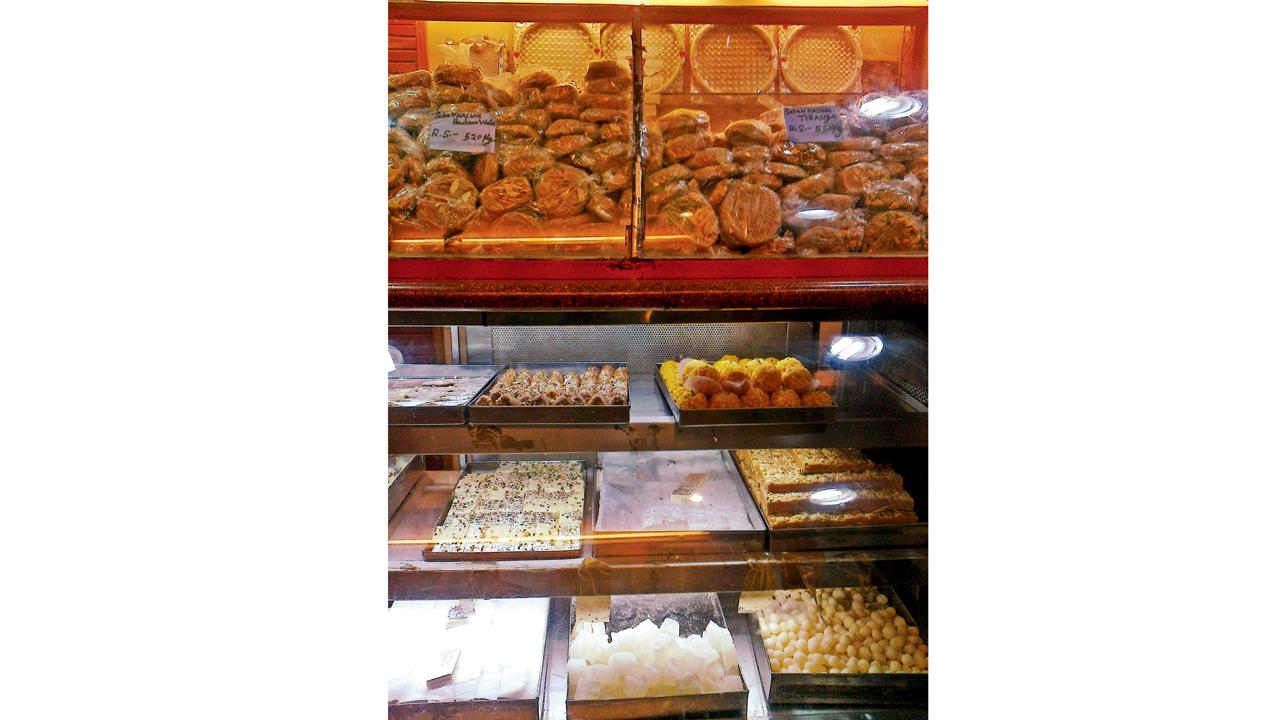

One of Pushpesh Pant’s favourite food memories from Delhi is the taste of the famous sohan halwa from Ghantewala halwai at Chandni Chowk. The sweet shop, set up in 1790, reopened this August after a decade-long hiatus. Pics/Wikimedia Commons

What about “Mughal cuisine”, one might ask. Turns out, this is one of Pant’s pet peeves. “We overrate the Mughal influence on Delhi food. Most Mughal rulers did not have the money to enjoy grand food. Very few ruled from Delhi, and many had hired cooks from Lucknow. Humayun, who succeeded Babur, spent most of his life in exile, where some accounts suggest he developed a taste for the humble besan ki roti and millets,” says the academician. Mughaliya influence on the cuisine is no greater than that of Turko-Afghan rulers (such as the Khilji dynasty), or settlers such as the Baniya community, offers Pant.

“Why don’t people talk more about the mark the Baniya community left on Delhi, establishing misthan bhandars which sold sweets and vegetarian savoury snacks that everyone could eat? Some of these are as old as the French Revolution,” he says, referring to Ghantewala Halwai in Chandni Chowk, established in 1790. It survived centuries of turmoil in Delhi, only to be shut down in 2015. These mishthan bhandars were the direct predecessors of the modern-day Haldirams and Bikanervala, which Pant interestingly compares to the American diner phenomenon. “Just like those diners, these places are accessible to all, and the prices are affordable. You can pick what you want to eat, whether it’s a dosa or pav bhaji for the adults or a pizza for the children. There’s something for everyone,” says Pant.

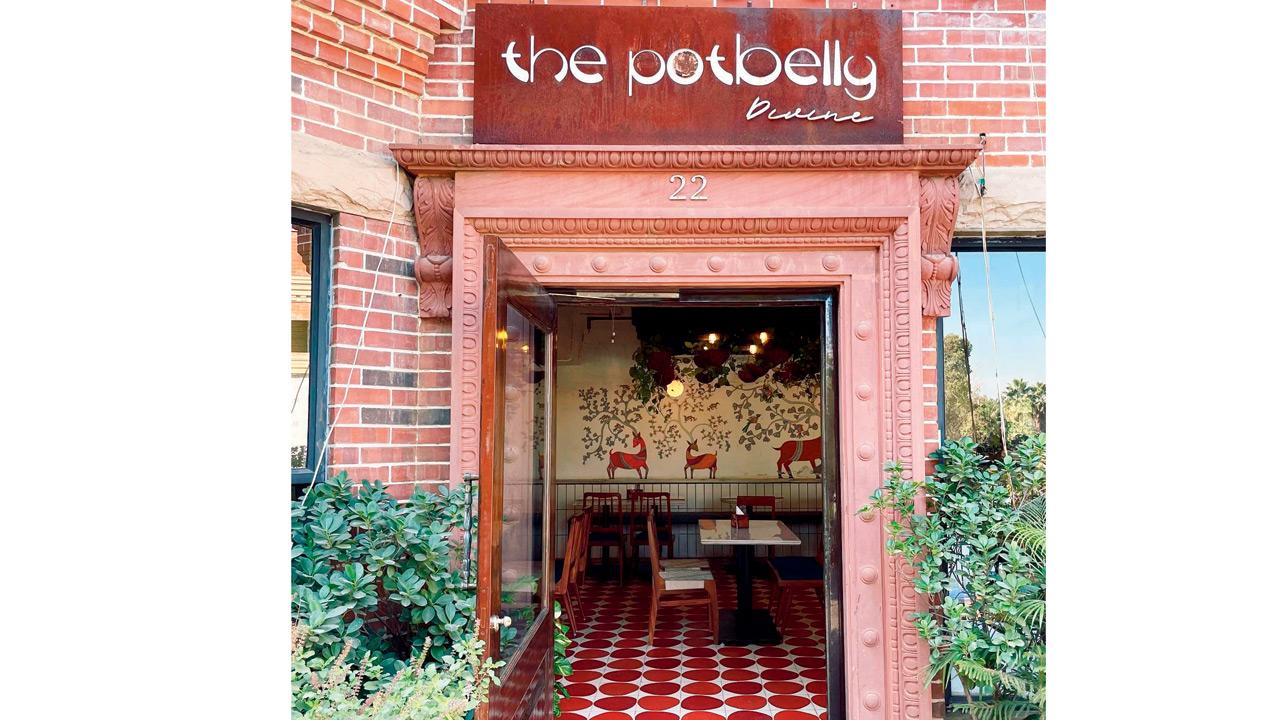

Delhi’s food scene is a microcosm of all the communities settled there. Pictured above is The Potbelly Rooftop Cafe (Bihari cuisine). Pic courtesy/The Potbelly Rooftop

Accessibility and affordability form a large part of the discourse in Pant’s book, in which he writes about how Delhi’s food culture was predominantly “democratic” in earlier days, whether it was at inexpensive dhabas or the renowned India Coffee House, also known as the Price Rise Resistance Movement (PRRM) cafe, run by worker cooperative societies which offered subsidised food and coffee. The PRRM coffee house drew not only cash-strapped students like Pant in his college days but also nation-builders such as MS Swaminathan (father of the Green Revolution) and intellectuals and artists such as MF Husain. “When I moved from Nainital to Delhi [as a teenager], the primary issue was what I could eat and couldn’t, and it was directly related to money. Spaces like PRRM were not just affordable for a wider class of people—a dosa cost 27 paise, including tax—but it was a truly democratic public space where one could voice dissent and hold political discussions and have passionate disagreements as well,” recalls Pant.

A 16th-century miniature painting depicts Babur at a banquet, where the menu included roast goose. Pic/Wikimedia Commons

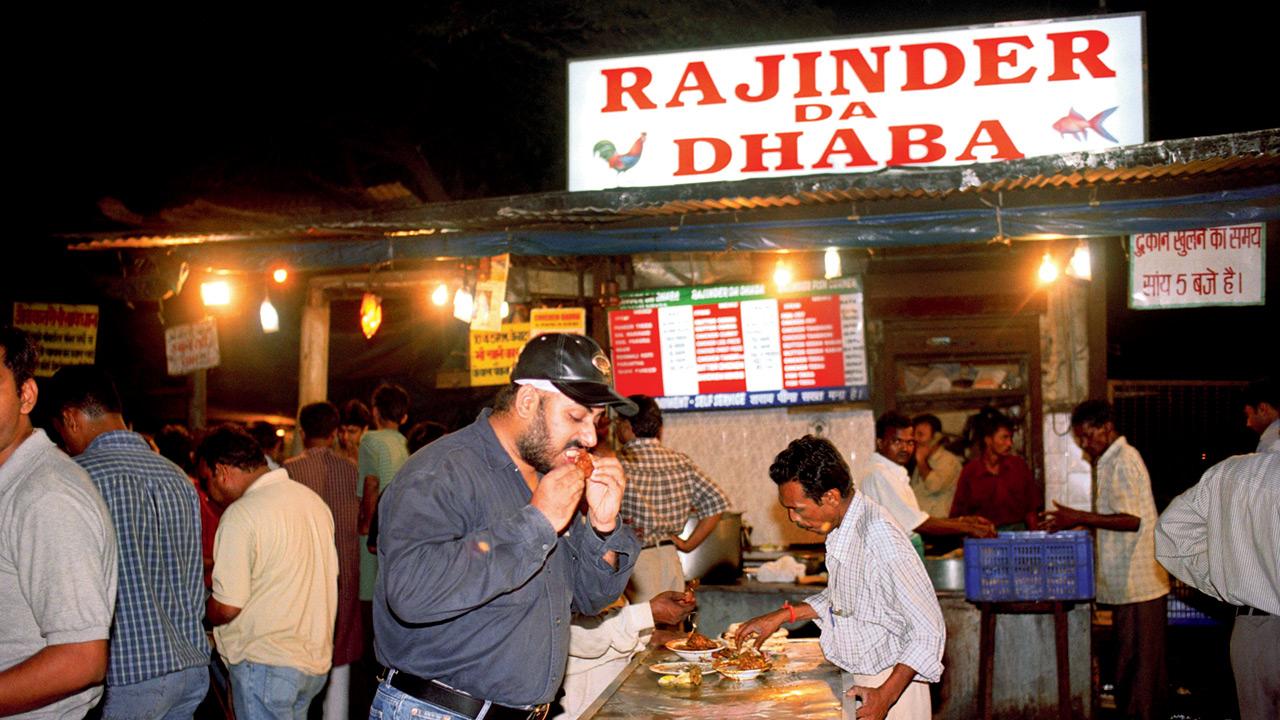

On the other hand, dhabas gave patrons a sense of anonymity, encouraging free expression. “Dhabas were where the real intellectual ferment took place,” says Pant, “People were freer, and the food was cheaper. Everyone mingled over the sugary tea, and the conversation was scintillating. One could eat a full meal for 70 paise at a dhaba. People would bring their own whiskey, buy fish by the kilo and just eat, talk and listen. Those were the last days when people ate unconsciously while sitting on the roadside. Now even places like Raju Ka Dhaba [at Green Park Metro station] have become gentrified.”

Gentrification of such spaces has occurred throughout the capital, cutting off access to lower-income patrons and dampening the unfiltered discussions of yore. “Where is the cheap food anymore?” he questions, “There is a connection between cheap food and freedom of speech. The minute you enter a genteel establishment, the waiters are careful not to get too familiar. Patrons speak in hushed tones, too. There’s no eavesdropping on the conversation at the next table and jumping into a political debate with them.”

With the sense of anonymity they bestowed on patrons, dhabas were where the intellectual ferment truly happened, says Pant. Pic/Getty Images

Perhaps the closest parallels that Mumbai has to offer are our ubiquitous vada pav stalls. Pant agrees: “Mumbai has places where you can pick up cheap food on the run, like vada pav centres. There is neither the space nor the time to sit and enjoy a meal and a discussion with fellow patrons in this city.” This on-the-go snack is not just an economic tummy-filler, but a political icon from the previous century, when the city was in the grips of mill worker strikes. Several historians have written about how, when the textile mills began to shut in the 1980s, some of the workers who had lost their jobs began to sell vada pav. The rest of the mill workers would buy their vada pav and eat it on their long walk home, discussing how best to raise their demands before the authorities.

Another quintessentially Mumbai instance of how food and politics are closely tied are the Sindhi refugee camps, such as those in Khar and Chembur, which eventually turned into cultural and gastronomic hubs. When Sindhi migrants first settled here post-Partition, intellectuals and activists would go to these camps and break bread with them, while discussing the problems faced by the community.

So, where would Pant recommend a visitor grab a meal if they’re in Delhi for a day? His love for good, solid food at affordable prices shines through: “Don’t fall for tourist traps. I’d say have chole bhature at Haldiram for Rs 140. For non-vegetarians, I’d send them to kebab shops at Nizamuddin or Shaheen Bagh. Food outside the walled city [Old Delhi]is both tastier and more affordable.”

Of course, with Delhi’s food scene so changed, some of Pant’s favourite food memories are from home. “My son is a gifted cook. We host guests every now and then, and the menu usually includes dal, sabzi, roti, along with Kashmiri rogan josh, Chettinad fish or Patrani machhi,” says Pant. And now, the Pant family can end their feast with the famous ghee-soaked sohan halwa from Ghantewala Halwai, which reopened its doors in August after a decade-long hiatus.

Ah, sweet nostalgia!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!