Slip of tongue or not, Rashtrapatni is a loaded term. So, what exactly can we call women presidents in India?

President Droupadi Murmu greets supporters after being elected as the country’s new president in New Delhi. Pic/Getty Images

The “Rashtrapatni” commotion in Parliament on Thursday over Congress lawmaker Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury’s purportedly accidental mis-gendering of President Droupadi Murmu put the spotlight on how designations haven’t evolved to reflect inclusivity of genders.

ADVERTISEMENT

Women BJP parliamentarians, led by Union Minister duo Smriti Irani and Nirmala Sitharaman, denounced the Congress for “demeaning women and the tribals of India”. Irani demanded an apology from Sonia Gandhi as BJP lawmakers yelled and waved signs in the former’s face. Irani accused the Congress leader of having approved the “denigration of a woman in the highest constitutional post,” charging, “You approved of Droupadi Murmu’s humiliation.”

In a parliamentary democracy like India, the presidency may be largely ceremonial, but Murmu, the country’s second female president (and first tribal one), faces several expectations. Eliminating the patriarchal term Rashtrapati in favour of something more gender-inclusive or gender-neutral could now be foremost.

“We should’ve fixed this a long time ago,” top linguist and grammarian Pabitra Sarkar says. “Shamefully, on the one hand, we seize every chance to emphasise ‘our ancient and evolved linguistic traditions,’ and on the other, we can’t get rid of sexist terminology, even in addressing the highest office in the land.”

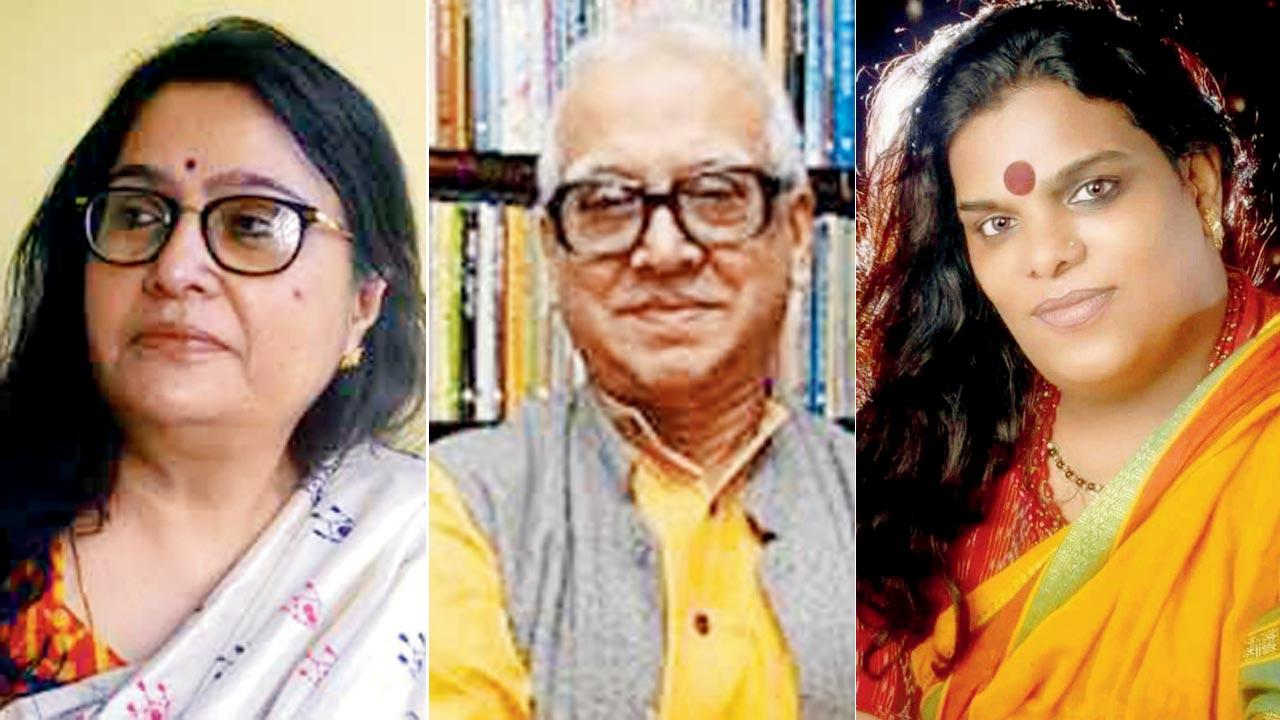

Anita Agnihotri, Pabitra Sarkar and Gauri Sawant

The word pati, explains Sarkar, etymologically means lord or master. “This is a deeply problematic word even by itself, since it comes from adhipatya [authoritative control],” he says, “This patriarchal term is also used across the Indian subcontinent for husbands. When suffixed it can mean leader of a gathering [sabhapati],

National President [Rashtrapati], head of the army [senapati]—all terms that assume these are men-only positions.”

Language is the most powerful way that sexism and gender discrimination are unconsciously passed down generations. “Language ‘discreetly’ reproduces social status and power disparities linked to appropriate social duties,” Sarkar continues, “Because of grammatical and syntactic principles, feminine nouns often stem from equivalent male forms. Additionally, the structure of many languages assumes that a man is the prototype human being. Masculine nouns are frequently used to refer to both men and women in a generalised manner [as in the case of Rashtrapati]. This often invisibilises women.”

Sarkar is echoed by Bengali author and poet Anita Agnihotri, who is also a retired bureaucrat. “The word for wife, patni, immediately connotes servitude and a hierarchically lower position because it derives from the male pati. Because of this, when you call a female president Rashtrapatni, it takes on polyandrous overtones.”

Sarkar and Agnihotri offer Rashtrapramukh as solution.

More than 1,900 kilometres away in Mumbai, Marathi feminist writer Vandana Khare believes Rashtradhyakshaa or Rashtradhyaksh would also work. She laments the subtle gender prejudice in language, and emphasises that gender-fair language can visibly promote equality. She underlines how “linguistic abstraction very softly depicts women less favourably and discriminates ever so casually,” and feels the best way to combat gender bias is to push for gender-fair expression.

Bollywood lyricist-poet Hasan Kamal says those defending Rashtrapati for women presidents are surreptitiously pushing benevolent sexism—a subtler prejudice which boxes women as pure, kind, gentle, and in need of men’s protection, thus justifying male dominance. “This is in sharp contrast to hostile sexism, which includes derogatory portrayal of women and negative feelings toward them in order to justify male power, traditional gender roles, and men’s consideration of women as sexual objects,” he says, while suggesting the Urdu option of Sadr, which translates to head. He smiles, aware that in the current socio-political climate, this would never be an option as “Urdu is marginalised as the language of Muslims.”

Another film lyricist, Raj Shekhar, feels Chowdhury’s apology would bring the curtain down on the brouhaha. “He is a Bengali [the language doesn’t assign gender to nouns]. As a Bihari, I also often mix up gender when I speak,” he says admitting he has been ridiculed for this quite often. “Extreme intolerance of this kind is linguistic apartheid. It is as if a select few decide what passes as pure Hindi, and who can or cannot speak it.”

Even in the South, where matrilineal communities still exist, there is no differentiating term for female presidents. While the President is Janatipati in Tamil, s/he is still Rashtrapati in Malayalam, Kannada, and Telugu.

Dr AL Sharda of Population First, an advocacy and communication initiative that works on health and population issues from a gender perspective, feels more sensitisation is needed, which will come with more representation. “Of the 15 presidents thus far, only two are women. More women in the position will drive the

change needed,” she feels.

She may have a point. India’s record of women’s representation in Parliament is abysmal. Until August 15, 2021, when the Taliban took over, even Afghanistan had more women legislators than India—12.2 per cent of the total seats, as against Afghanistan’s 27.6 per cent.

Bengaluru-based women’s rights activist Madhu Bhushan says: “Language holds up a mirror to society’s toxic masculine glory. Resistance to gender-fair language comes from an inability to let go of a deeply entrenched patriarchal mindset.”

But any such new nomenclature should not get stuck in cis-binaries warn LGBTQIA+ rights activists. “Since we’ve had Muslim, Dalit and tribal presidents, it’s high time we have one from sexual minorities too,” says Gauri Sawant, trans rights activist and founder of the NGO Sakhi Char Chowghi. When asked for an LGBTQiA+ friendly term, she is stumped and wonders why we can’t go with ‘President’ itself. “We translate Governor to Rajyapal for states and union territories, but don’t we stick to using Governor even in Indian languages when it comes to the Reserve Bank of India?”

When the US almost had a first gentleman

When Hillary Clinton ran for president, the US had to mull over the prospect of her husband Bill Clinton becoming ‘first gentleman’. Addressing this on the Jimmy Kimmel show, Hillary had conceded, “…he [Bill] was running to break the iron grip that women have had on being spouse of the president. And so, I think we’ll have to figure out what to call the male spouse of a female president,” and pondered, “First dude? First mate? First gentleman? I’m just not sure.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!