A former central banker’s new book explores the historical and socio-cultural legacy of paper currency in India

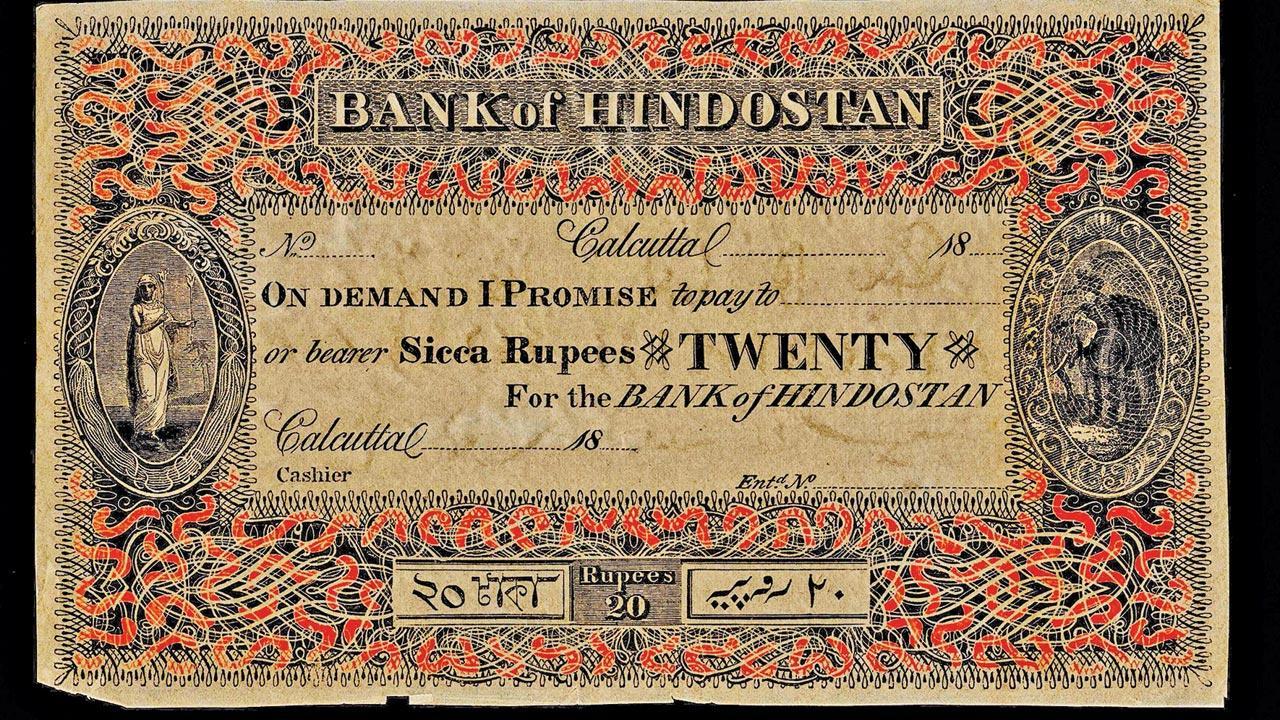

A specimen note of 20 sicca rupees issued by the Bank of Hindostan, printed in dark brown, with red and black. Pic courtesy/Rezwan Razack

Long before paper money became accepted currency in the Indian sub-continent, “hundies” were the norm. These “versatile paper documents”—the use of which began during medieval times—served either as promissory notes to borrow and lend money, or as trade bills to facilitate sale of goods, and as remittance instruments to transfer funds from one place to another. “However, they were specific in their usage and purposes. While they were transferable, they were not designed to circulate amongst the public and were used by a closed community of Indian bankers, merchants, governments and others initiated in methods of finance,” says Bazil Shaikh, author and former central banker, who headed the team that conceived, researched and curated the RBI Monetary Museum in Mumbai.

ADVERTISEMENT

His new book, The Conjuror’s Trick: An Interpretive History of Paper Money in India (Marg Publications), is a deep dive into the socio-cultural legacy of paper currency, offering insights into how it evolved—in nature, design and value—first during the colonial rule and later, in post-Independent India.

An early banknote of the Government Bank, Madras, 1816, promising to pay 2 star pagodas or 7 Arcot rupees. Pic courtesy/Rezwan Razack

Though the hundi network spanned the region through the 1900s, paper money’s origins in the country, says Shaikh, actually goes back to the late 18th century, when private banks circulated “banknotes”. This was the era of free banking, when there were fewer restrictions on the setting up of banks in India, and banks were free to issue banknotes that were convertible into coins and circulated as money, without a lender. “Banknotes were interest free promissory notes. They were typically issued in lieu of coins. They were designed to circulate from person to person and could be encashed by the holder on demand at the bank during working hours, for the sum of money the note promised to pay. These notes provided users convenience of transactions and provided the issuer banks access to interest free funds, much in the same way that current deposits do today,” he tells mid-day.

But, the unchecked circulation of banknotes brought with it several challenges. “For instance, in the 1820s, notes of the Bank of Hindostan, Bank of Bengal, The Commercial Bank, the Calcutta Bank competed with each other for circulation in Bengal. To the extent the notes issued exceeded the reserves held by the bank. What they were doing was conjuring money out of thin air,” says Shaikh. “Prudence, however, required that banks restrict the notes issued to a proportion of the reserves held. The convertibility of the banknotes into silver and gold coins on demand sought to deter over issue of notes.”

The first series of Government of India notes was designed by the Bank of England on the lines of the five pound note and bore the portrait of Queen Victoria. Pic Courtesy/RBI Monetary Museum

Most interesting is the role of the Bank of Hindostan, established around 1770 in Bengal, whose notes became the “flavour of the times” for bandits and counterfeiters.

“The idea of a bank as a repository of money has traditionally fired the imagination of bandits and robbers—be they crusty villains or suave fraudsters,” says Shaikh, adding, “Newspapers reported a case in 1795 where plans of a formidable gang of robbers planning an attack on the Bank of Hindostan were thwarted. Interestingly, the gang included English, Portuguese, Italian and other foreigners.”

Though it was believed that banknotes printed in Britain on watermarked paper would be impossible to forge, forgeries of notes soon appeared commencing a new line of expertise. Amongst the earliest reported forgeries was that of a Bank of Bengal note in 1806. “Interestingly, in 1819, the Bank of Hindostan attempted to inform the public regarding the features of a genuine note. This early attempt at public education led to panic and a run on the bank. Notes worth 18 lakh sicca rupees had to be encashed to dispel public anxiety. To its credit the bank successfully weathered the run,” says Shaikh.

The Rs 50 King George V note released in 1930. Pic courtesy/RBI Monetary Museum

Free banking ended in 1861 when the Paper Currency Act prohibited banks from issuing banknotes, and vested the monopoly of note issue with the Government of India. Currency notes were a liability of the government and were backed by assets. Shaikh says that this was because, when the government took over the currency function, “notes were convertible into silver rupees”. “As the issuer of the notes, government was liable to pay the bearer the stated sum,” he says.

For the longest time, the country was divided into geographical circles or Currency Circles, where alone the notes were legal tender and could be exchanged for coins. It was nearly half a century later that paper currency use was universalised. Finally, in 1935, the Reserve Bank of India was instituted to manage elastic currency, whose “volume can be increased or decreased in response to the needs of the economy.”

Bazil Shaikh

Among the most popular currency was the King Portrait series, introduced in the 1920s, and which bore the image of King George V.

“The imagery of the notes evoked awe and majesty and sought to convey the grandeur of Empire,” says Shaikh. While this was also the period when the stirrings of nationalism were gaining pace, it took another twenty years, in the wake of the Quit India movement, for currency to be used as an instrument of protest. “The leaderless movement with the youth at its vanguard, started inscribing the words ‘Quit India’ on notes leading to the promulgation of the Legal Tender (Inscribed Notes) Ordinance of 1942, which withdrew the legal tender character of notes inscribed with political messages,” he adds.

Post-independence, a string of efforts were undertaken to change the visual identity of paper currency. “To start with, notes of independent India replaced the King’s Portrait with the national emblem. Based on Lion Capital of the Ashoka Pillar at Sarnath, it was devised as an aggregative symbol reaffirming contemporary India’s commitment to peace and compassion.” The Brihardeshwara Temple at Tanjore (Thanjavur) graced the R1,000 note, while the Gateway of India was the motif for the Rs 5,000 note. Similarly, on the Rs 100 note, the Hirakud Dam replaced the elephant, while a farmer driving a tractor —an allegorical representation of farm mechanisation celebrating the green revolution—replaced the deer on the R5 note. Where the Mahatma Gandhi series sought “to reaffirm our commitment to Gandhian values”, the latest series of notes, he says, highlight India’s cultural and historic diversity.

One of the biggest breakthroughs for money in new India, however, he says, is how it’s being reimagined in the digital format. “The world is witnessing a major disruption today… Power shifts are taking place between the state, corporates, communities and individuals. These have influenced money. Local complementary currencies on one end of the spectrum and cryptocurrencies that recognise no borders on the other end of the spectrum, are challenging the present system of money as a central bank liability. Central banks, on their part, are responding by seeking to introduce Central Bank Digital Currencies. These developments hold promise as well as invoke concerns for the economic organisation of society, surveillance and freedoms. We live in interesting times.”

1806

The year in which a Bank of Bengal note was forged, in one of the earliest reported forgeries

Demonetisation of 1978 Vs 2016

The 1978 Ordinance demonetised notes of Rs 1,000, Rs 5,000 and Rs 10,000. “Very few people in India had the opportunity to use or even see these notes. The demonetisation thus, did not have any impact on the day-to-day lives of the common person. On the other hand, in 2016 when the minimum daily wage was about Rs 250, the Rs 500 note was very much a part of the experience of the common person. The move, which demonetised about 86 per cent of the currency in circulation, thus impacted virtually every household. The informal sector, which constitutes the mainstay of the economy was especially impacted,” says Shaikh.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!