It’s not theirs, it’s not ours—it’s everyone’s. The first in a series that debunks the governor’s claim about Gujaratis and Marwaris building Bombay, looks at the role of Pathare Prabhus and East Indians

The Kolis are the oldest known inhabitants of the seven islands that make up this city, they have lived here for centuries—some say since 600 BCE. This community may not be as visible on the city’s bustling streets as they once were, but in a way, they still shape Mumbai’s identity. Their historical legacy is imprinted in the names of several neighbourhoods in Mumbai, including Sion Koliwada (homes facing the sea), Warli Koliwada and Mazagaon, a corruption of “machcha gaum”, ie fishing village. Pic courtesy/William Johnson, Sarmaya Arts Foundation

It’s our favourite bone of contention in Mumbai, and a few weeks ago, Maharashtra Governor BS Koshyari picked at it again when he said that the financial capital

of India would cease to be so if the Rajasthanis and Gujaratis moved away.

The Pathare Prabhus tucked in their nauvaris for war; the East Indians sighed in familiar resignation; In the Parsi baugs of this city, India’s Zoroastrian community clutched at their pearls; colourful expletives rang across Irani cafes fronted by Persian migrants; In history and architecture books, the British underlined their contribution. In Chinchpokli’s cemetery, a lone Jew—simultaneously a Baghdadi and a Bene Israeli—turned in his grave. Somewhere deep under the earth at Antop Hill, also lay an Armenian.

A panoramic view of Bombay, late 19th-early 20th century, by an unidentified photographer. Pic/Sarmaya Arts Foundation

A panoramic view of Bombay, late 19th-early 20th century, by an unidentified photographer. Pic/Sarmaya Arts Foundation

But most of us went back to hanging on for our lives in local trains and complaining about the come-and-go August rain.

It is broadly accepted that the British (as the East India Company and as Colonisers) sensed the potential in our fair and smelly port city, and stoked an ambition to create Urbs Prima in Indis (The first city of India). They welcomed mercantile families, encouraged industry by doling out tax benefits, turned a blind eye to illegal opium trade (but cultivated and auctioned it ), and allied with communities that enriched their lives—the Baghdadi Jews, who created jobs that brought the Bene Israelis out of the coastal villages and into Mumbai; Goans nannies and cooks, Parsi shipbuilders and cotton mill owners, Chinese craftsmen, and European engineers.

When Surat began to declined as a premier port city in the 18th century,” says Simin Patel, founder of Bombay Historical Works, who goes by Miss Bombaywalla on Instagram and Twitter, “Bombay offered relative economic, political and religious security, drawing a number of Gujarati merchant communities to its shores and fortified settlement. Among Bombay’s most prominent international religious exiles was the Aga Khan; David Sassoon too was fleeing the authorities

in Baghdad.”

This century view of Saat Rasta Junction from Raheja Vivarea near Mahalaxmi station. Pic/Ashish Rane

This century view of Saat Rasta Junction from Raheja Vivarea near Mahalaxmi station. Pic/Ashish Rane

However, Kurush Dalal, archaeological researcher, would like us to look further back. Way, way back.

“Why did the Portuguese come to Bombay in the first place? There is evidence that 1st century onwards, the islands that became Bombay were already a trade centre. Historical structures such as the Kanheri caves, the Mahakali caves, the Mandapeshwar in Borivli could not be built without a thriving economic and social structure around them. The inscriptions found in them date these cave structures between 1 to 8 CE. Trade backing supported the growth of the metropolis around the port.”

The Pathare Prabhus, who followed Raja Bimba to northern Konkan from Gujarat in the 13 century, are broadly recognised as the first migrants to this region. Raja Bimba established his capital at Mahim and ruled a large portion of the present-day Raigad-Thane-Konkan territory. In what is now south Mumbai, was then a babool tree forest at the foot of a hill near Babulnath Temple. “There is evidence of the presence of Arab traders in Bombay and Salsette in the time of Raja Bimba,” says Dalal Andre Baptista, archaeologist and cultural heritage professional, bolsters this theory: “The north Konkan coast was cosmopolitan right from 1 to 2 CE. There is evidence of Indo-Roman trade. The ancient ports of Sopara, Kalyan, Thane and Chaul, in Raigad district, are mentioned in Greco-Roman accounts of trade. The coast was left to its own devices and there was a general autonomy. There was trade with ports along the Red Sea, the Mediterranean and the East coast of Africa.”

Rajan Jayakar, historian and solicitor, holds that the Pathare Prabhus were part of Raja Bimb’s entourage as he crossed over from Devgiri to Salsette island and to Mahim, then called Mahikavati around 1296, after Allauddin Khilji attacked Devgiri. “Historian Dr. Gerson D’Cunha says that even Bimb was a Pathare Prabhu,” says Jayakar. “They were certainly Kshatriyas; as our last names are war or victory-oriented: Jayakar, Vijayakar, Senjit and so on. The Chaukalshis, Paachkalshis and Palshikar Brahmins also came with Raja Bimb.”

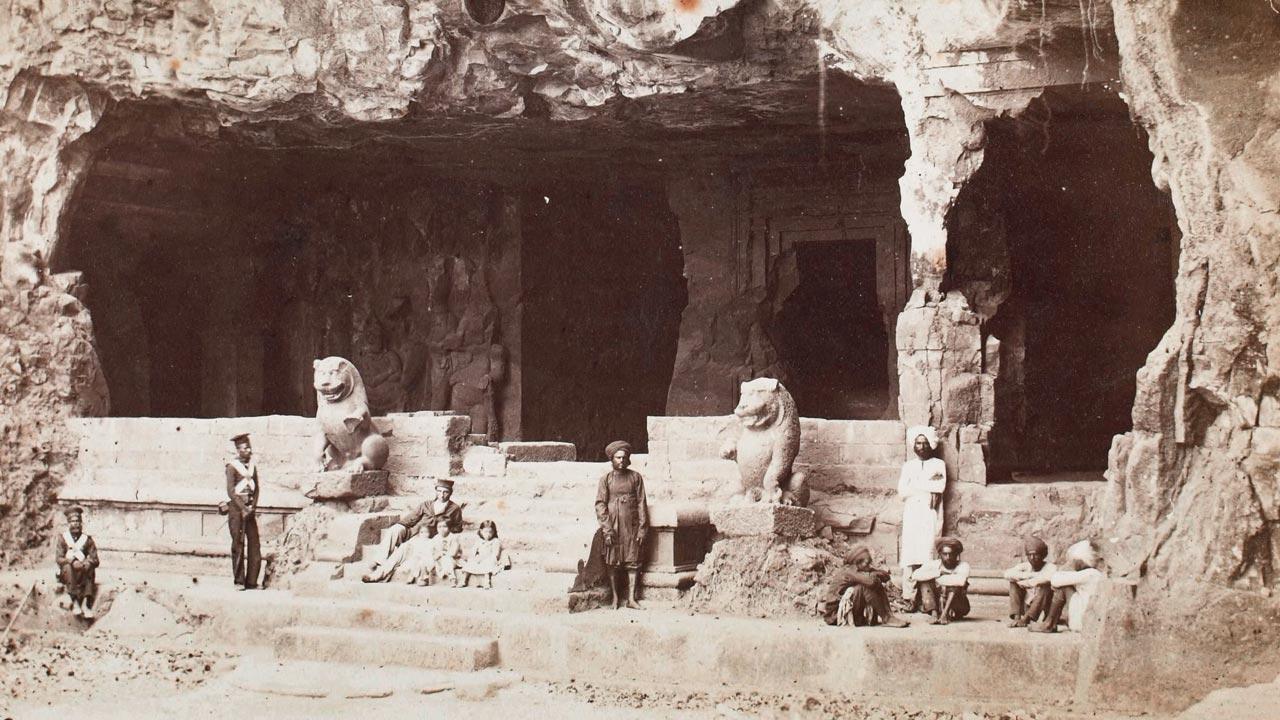

Cave clusters such as the Elephanta, Kanheri, Mahakali Caves date back to 1-2 BCE. Historian Kurush Dalal says that such elaborate community-religious structures could not be built without a rich and thriving social and economic structure behind them. Elephanta Caves, Bombay, late 19th Century. Attributed to William Johnson and William Henderson. Pic/Sarmaya Arts Foundation

Cave clusters such as the Elephanta, Kanheri, Mahakali Caves date back to 1-2 BCE. Historian Kurush Dalal says that such elaborate community-religious structures could not be built without a rich and thriving social and economic structure behind them. Elephanta Caves, Bombay, late 19th Century. Attributed to William Johnson and William Henderson. Pic/Sarmaya Arts Foundation

Raja Bimb built the temple of his patron goddess Prabhavati, now known as Prabhadevi Temple, which gives the region its name. “Bimb also established a court of justice, nyaygaon, which is now Naigaon near Parel,” says Jayakar. “Bombay had the best harbour on the east of the Cape of Good Hope. The Pathare Prabhus soon became landed gentry, owning tracts of land on Bombay Island and lived in Dhobi Talao, Chira Bazaar, Fanaswadi (literally, jackfruit orchards), Thakurdwar, and Girgaum. Some of them took on lease salt pans at Wadala and Bhayandar. They had coconut wadis in Mahim. The unique edge the Pathare Prabhus had over other communities of the time was they were literate; even the women of the house knew how to read and write, right from Portuguese regime onwards. They slowly became bureaucrats of the kingdom; or clerks and bailiffs, collecting rent for the ruling dynasty.”

The Portuguese came with the intention of trade and conversion, with more focus on the latter. They converted the upper caste Brahmins and Kshatriyas first, in the hope of a trickle-down effect through the caste system. “The late veteran journalist, Olga Valladeris, used to say her ancestors were Pathare Prabhus converted by the Portuguese,” continues Jayakar. “During their rule, some of the Prabhus remained as the bridge between the new rulers and the ruled, and become unpopular among their people, who saw them as perpetrators of Portuguese atrocities. Some even went back to Gujarat to avoid conversion, and some converted to Christianity.”

The Prabhavati devi temple, which gave Prabhadevi its name, was built by the Pathare Prabhus who migrated to Mumbai in the 13 century. Pic/Atul Kamble

The Prabhavati devi temple, which gave Prabhadevi its name, was built by the Pathare Prabhus who migrated to Mumbai in the 13 century. Pic/Atul Kamble

There is a legend among the Pathares, who were owners of the Prabhavati devi temple: When the Portuguese began destroying temples and desecrating idols, the Prabhus immersed the idols in a well nearby. At the commencement of British and East India Company. rule, sometime in early 18th Century, the goddess Prabhavati visited a successor of the original owner in his dreams, and requested him to remove them from their watery hiding place. She also requested that he build a new temple in place of the old, which was done. In 1975, the trustees of the Prabhadevi temple wanted to remove the 13th century idols that were not in good condition. “They approached the then director of the erstwhile Prince of Wales Museum, Mr Gorakshekar [a Pathare Prabhu] for help. He sent his team to remove the idols carefully and brought the idols to the museum,” says Jayakar.

When the islands were passed on to the British by the Portuguese in 1661, the Pathares remained in the system. In 1862, out of the first four solicitors of Bombay High Court, three belonged to the community and the first Indian judge of the High Court was also a Pathare Prabhu. Among a population of 5,000 members of the community were architects, engineers, chartered accountants and doctors. “They preferred liberal professions,” says Jayakar.

Solicitor and community historian Rajan Jayakar traces his ancestory to the Pathare Prabhus, Mumbai’s first immigrants, who came with Raja Bimba. Pic/Sameer Markande

Solicitor and community historian Rajan Jayakar traces his ancestory to the Pathare Prabhus, Mumbai’s first immigrants, who came with Raja Bimba. Pic/Sameer Markande

Baptista, who belongs to the East Indian community, reminds us that we forget the land because it was always present, but it was donated by (or taken away from) the original inhabitants for the cultivation of a metropolis. The Kolis (fishing community), East Indians, Agris (who managed salt pans), Sonars, Kumbars (potters), Bhandaris (toddy tappers), Kunbis (agrarian community), Pathare Prabhus, the Panchkalshis—the original stewards of the land are usually left out in favour of the urban creators. “You can recognise the original inhabitants by their last names, derived from where they lived: Varlikars from Worli Dongar [hill], Dahisarkars, Edwankars,” he says. Baptista is involved in the heritage-design project in Khotachiwadi, This Ground, Plus: Khotachi Wadi in Design Context. “Fashion designer and Khotachiwadi resident James Ferreira found records showing that his great, great grandfather donated the land on which the Mahim Causeway is built. In awe of everything that is built, the land is usually forgotten,” he says.

Next in the series

What differentiated Portuguese rule from the that of the British?

This article is part of Mid-day's Mumbai Konachi? series that looks at those who played a critical role in building Bombay.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!