In her new book, The Final Farewell, writer and researcher Minakshi Dewan talks about the different interpretations of funeral rites and ceremonies in the country. She breaks down the thorough process that led her to examine the deep layers that bind us all

India has several similarities across the rites and rituals of its funerary customs, which offer relatives a space to mourn and reflect, and a timeframe to process their grief. Pic/Getty Images

Although this topic was a tough one to research, what made it possible was the stories told to me; there were so many stories and anecdotes that came from the death workers and the families. It started as a personal experience I had with death. When I was performing my father’s last rites, I noticed that one of the funeral worker’s eyes were always red, and his voice had a slur. That made me curious about death work and the impact it had on the funeral workers who assisted in the rituals.

When I had gone to Haridwar to update the family records and immerse my father’s ashes in the Ganga, I spoke to the tirath purohit (pandits, locally known as “Pandas”, who maintain the genealogical records of families) and saw the messages left by my grandfather for his father, and so on.

The beliefs about what death really means and the accompanying last rites and rituals are very closely related across religions. For my father, we placed some ganga-jal and tulsi-leaves in his mouth, and read specific verses from the Bhagvad Gita, as a form of pre-cremation rituals. Among Parsis, there is a pre-death ritual, where they put drops of pomegranate juice in the dying person’s mouth. In Islam, specific verses of the Quran are read. It is all to do with the purity of the soul and assisting in a painless passage from this world to the next. The state of mind that a person has during the time of death is the state of mind that the person has after the person dies.

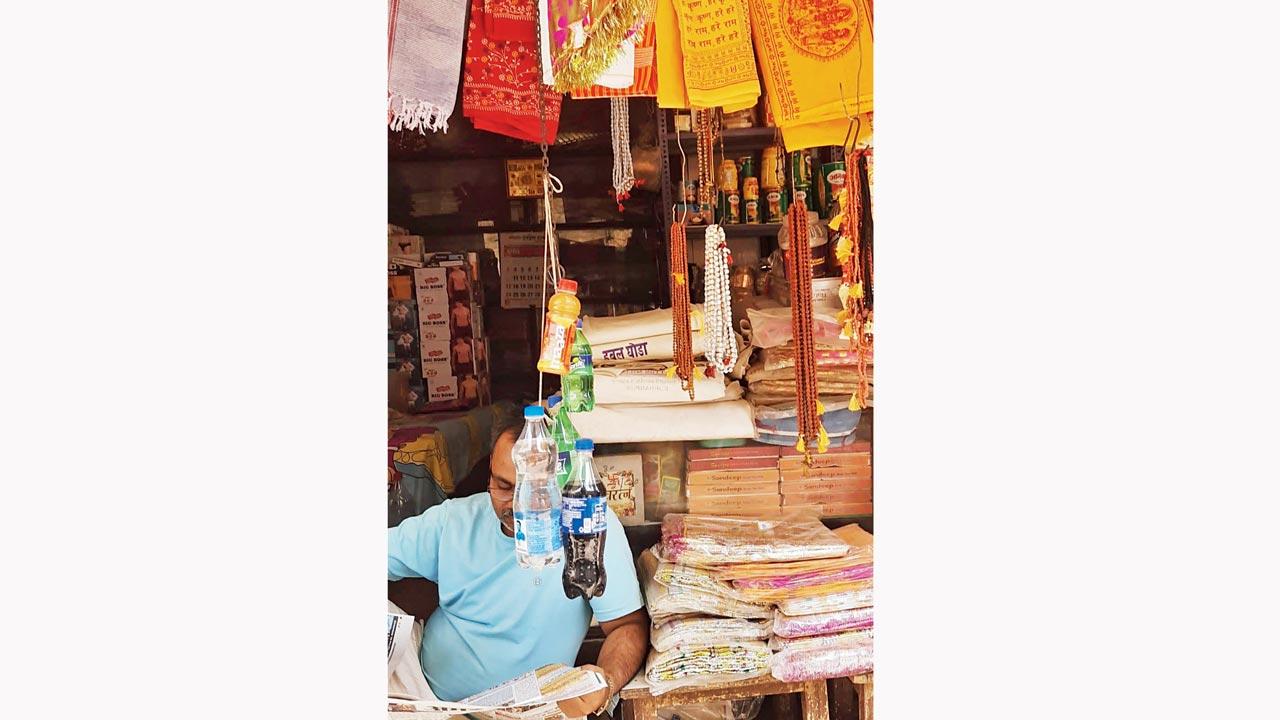

Shops selling goods used for funerary customs in Varanasi

Shops selling goods used for funerary customs in Varanasi

The COVID-19 pandemic brought the concept of death work and funeral rites to the forefront. Death rituals were condensed due to necessity, but that didn’t mean they lost their sacredness. Some aspects, like ritual baths given to the deceased, had to be forgone because of governmental guidelines. At the same time, with the atmosphere of death surrounding us every day, a lot of people demonstrated resilience and willingness to confront the reality. I remember talking to a volunteer in Pune during that time. He told me that a lot of women volunteers stepped in to help; girls as young as 18 to 19 years, who were assisting families to transport the bodies and perform the last rites, although some of them used to be uneasy at the sight of a funeral procession itself, earlier.

What was tough for me to understand was that specific communities or castes are not allowed to cremate their dead, and are denied a space to bury their family members. For example, the Kalbelia community in Rajasthan, like many lower-caste communities and Dalits across the country, are not allowed to bury their dead in the funeral grounds reserved for upper-caste groups. They bury their dead around their homes instead. Caste dimensions come into play when deciding where to bury or cremate the dead, and the people who are allowed to assist during these rites.

Minakshi Dewan

Minakshi Dewan

Talking to funeral workers highlighted the behind-the-scenes work that, from a public-health perspective, is an important part of our system. It’s extremely tough for the workers to work in such circumstances, and that’s why they succumb to different types of addictions. It’s a neglected and underpaid job, with a heavy psychological and emotional toll. It is difficult to handle a dead person, a dead body.

Funeral rites are the last to change, but there are many makeshift changes happening, both in the country and abroad. In Christian funerals, for example, there is a doubling and tripling, which involves different members of the family being buried in the same grave. Internationally, cremation is gaining ground as a popular funerary method. Other methods are also being explored. In North America, there are ‘water cremations’, and in Japan, there are ‘tree burials’, for example.

While this subject was difficult to write about, it was also challenging. In fact, I have learned more about unravelling the processes of life than death. It taught me more about life, what is happening around me. This book is actually about people who are alive and what this indispensable part of our lives really means.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!