A historian and former hotelier researching cheetahs for 40 years is out with a new book that discusses why India needs the animal back in the wild

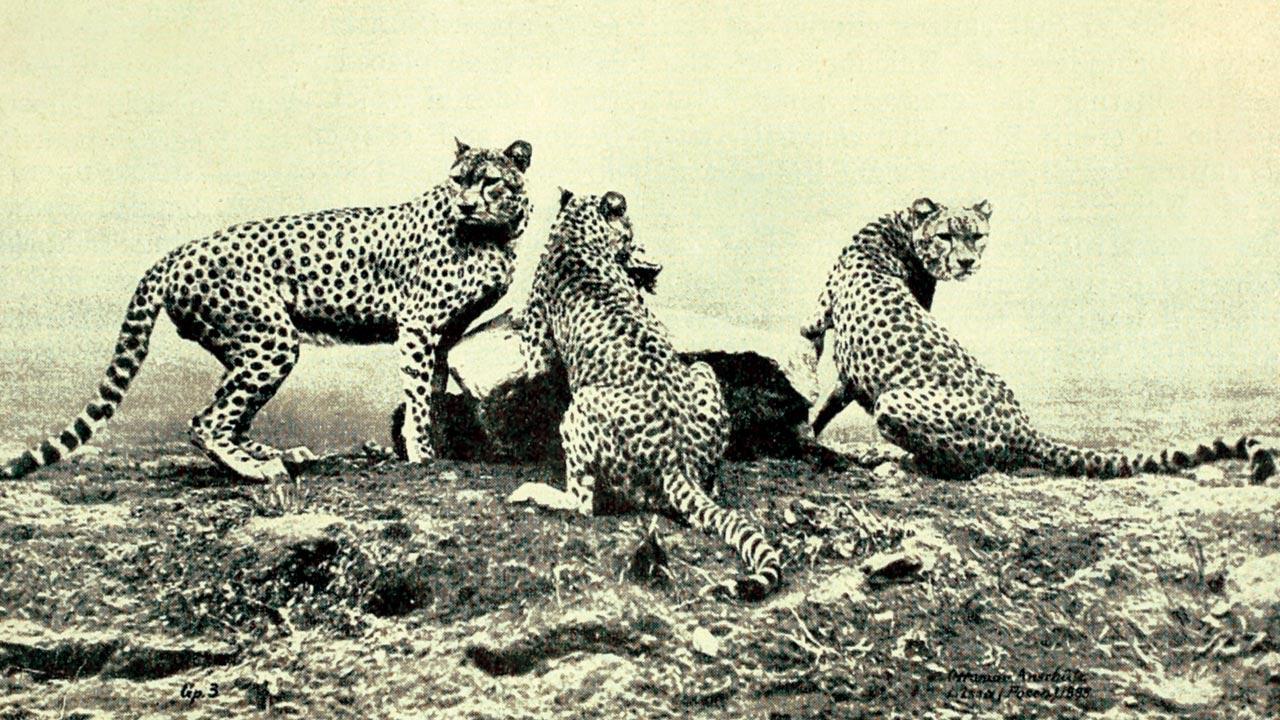

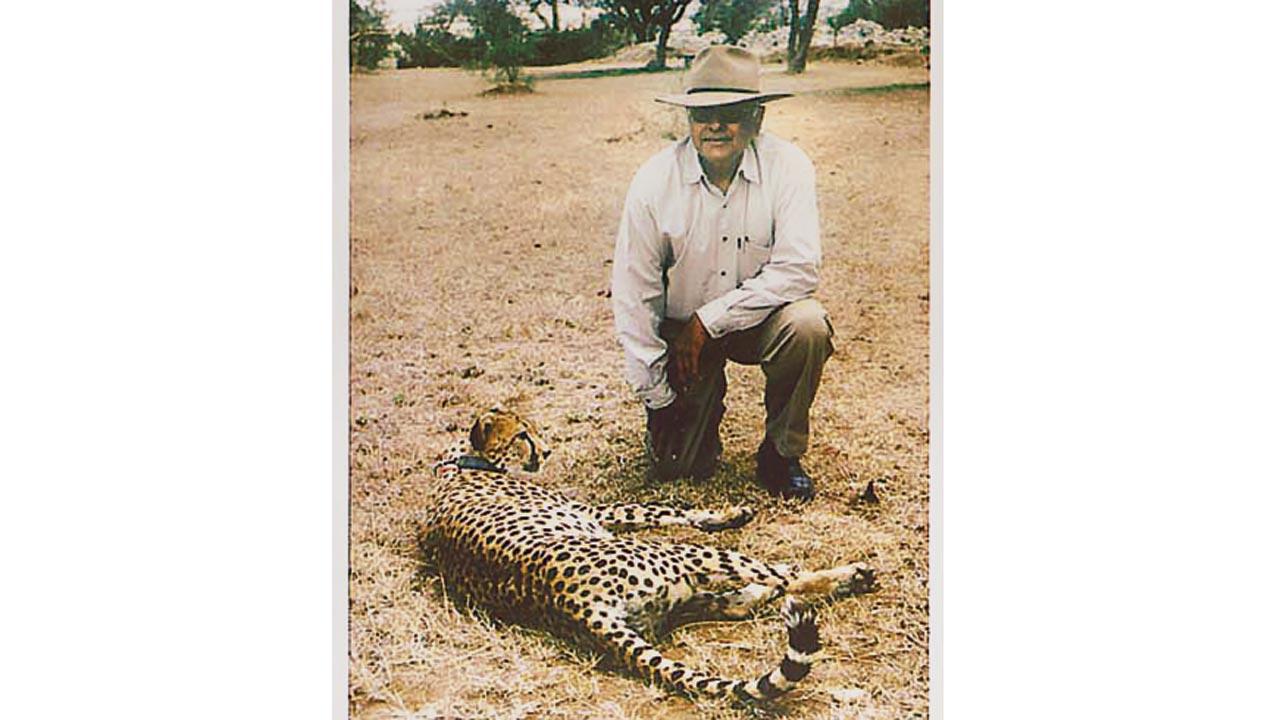

Possibly the earliest photograph of cheetahs in India, From Clay, 1901. Author’s collection. Pics Courtesy/The Marg Foundation

The conversation around translocation of cheetahs into India has been a long-running one. In 1984, when sightings of the feline creature were few in the country, and talks about reintroducing them into the wild from Iran had begun doing the rounds, an Indian hotelier became a curious student of the subject. “Back then, Maharaja Fatehsinh Rao Gaekwad of Baroda, who was president of the World Wide Fund for Nature-India, wrote to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, questioning the wisdom of importing cheetahs. In the letter, he claimed that India never had cheetahs. But, this was surprising because Baroda had been at the forefront of taming cheetahs and going hunting with the animal,” says Divyabhanusinh, who at the time was senior vice president, North India, at the Taj Group of Hotels. The then Deputy Minister for Environment YS Digvijaysinh, who knew of Divyabhanusinh’s interest in wildlife, passed on the letter to him, seeking his thoughts. “I put together a ‘Tentative Position Paper’ on the subject of the cheetah’s range and related matter.”

From there on, he says, things took a strange turn. The paper reached the Cat Specialist Group—Species Survival Commission of the World Conservation Union (IUCN)—which was meeting that year at the Kanha National Park in Madhya Pradesh. It was circulated and discussed widely. “A brief about my paper also appeared in their journal... after that, people thought that I was a cheetah expert with a doctorate on the subject.”

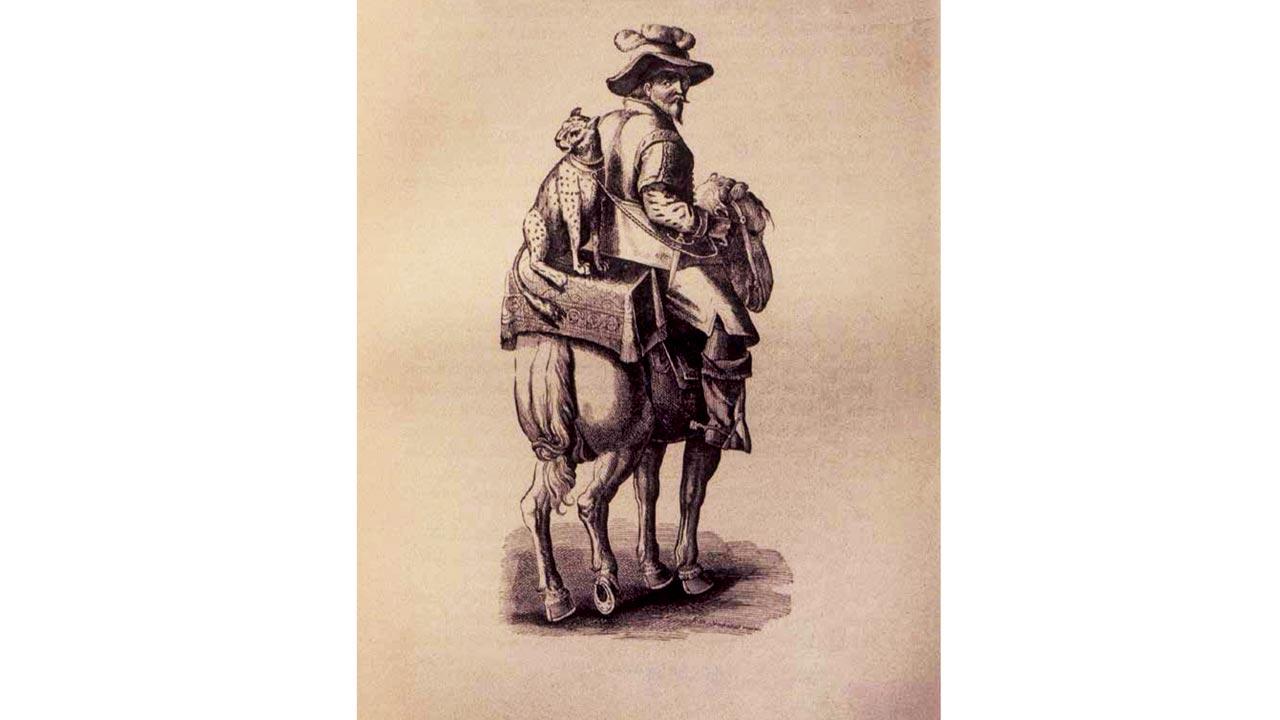

African cheetahs were taken to Europe from the Maghreb and Egypt for sport since ancient times, Jean Stradan, drawing. From Nott, 1886. Author’s collection

African cheetahs were taken to Europe from the Maghreb and Egypt for sport since ancient times, Jean Stradan, drawing. From Nott, 1886. Author’s collection

“I hadn’t seen a single cheetah in the wild,” Divyabhanusinh confesses in a phone interview from Jaipur to mid-day, clarifying, “...And I had no PhD.” Inundated with calls and requests to share his views on the matter, he decided to take this new role seriously. He reached out to experts in Sanskrit, Pali, Classical Greek and Latin, Arabic, Persian, Urdu and Marathi, who helped him make sense of the ancient texts that made references to the big cat. It’s how he was able to dig into the history of the cheetah, tracing its interactions with human beings to pre-historic times, until the animal’s extinction in the Indian subcontinent in 1997. The research which took nearly 10 years, resulted in the book, The End of a Trail: The Cheetah in India (1995).

His latest title, The Story of India’s Cheetahs published by The Marg Foundation, also delves into India’s most recent tryst with the wild cat—eight cheetahs from Namibia and 12 cheetahs from South Africa were released into the Kuno National Park in Madhya Pradesh in September 2022 and February 2023 respectively.

![Antelope and deer hunt, circa 1602-1604. The Mughals used trained cheetahs to capture prey during hunting expeditions in the wilderness. The animal’s population began to shrink, sometime around the reign of Aurangzeb (1658 to 1707). “They [the Mughals] were taking out huge numbers of cheetahs from the wild,” says Divyabhanusinh. Pic/Getty Images](https://images.mid-day.com/images/images/2023/apr/cheetah-ic-c_e.jpg)

Antelope and deer hunt, circa 1602-1604. The Mughals used trained cheetahs to capture prey during hunting expeditions in the wilderness. The animal’s population began to shrink, sometime around the reign of Aurangzeb (1658 to 1707). “They [the Mughals] were taking out huge numbers of cheetahs from the wild,” says Divyabhanusinh. Pic/Getty Images

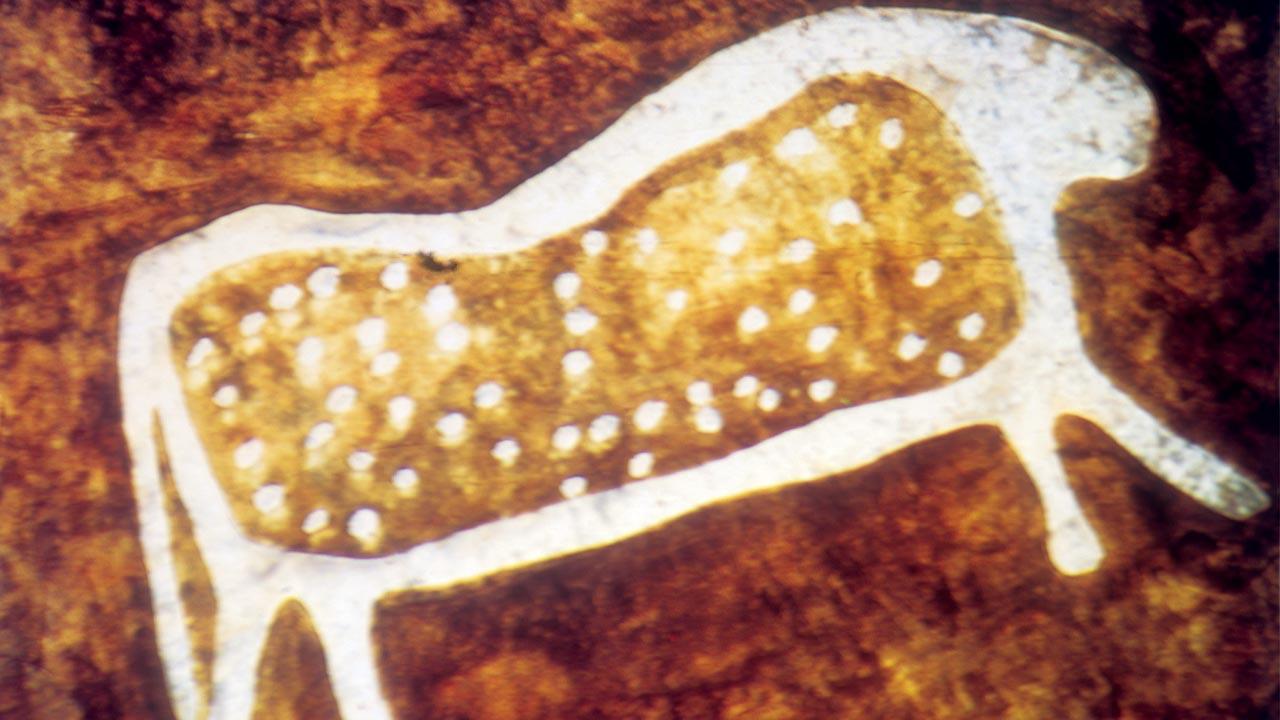

With the government’s initiative at Kuno being criticised by many as a “vanity project”, Divyabhanusinh felt the need to re-establish the cheetah’s relationship with India. “There are cave paintings of cheetahs [in a rock shelter in Kharvai, Madhya Pradesh] dating back to 2500 and 2300 BCE which clearly show that they inhabited the Indian landscape. Strabo, the great Greek geographer [64-63 BCE] of the ancient world, in his descriptions of India had said that every king here had a procession, where buffaloes [bos], leopards [pardalis], and tame lions [leontes] walked alongside,” says Divyabhanusinh, adding that Claudius Aelianus of Rome, who lived in 2nd century CE, and was a contemporary of Emperor Hadrian, had also pointed out how “Indians bring to their king tigers made tame, domesticated panthers [pantheras], and oryxes with four horns”. “The panthers are cats that hunt... the cheetah is the only wild cat that could be tamed,” he says.

The most interesting reference of the cheetah in Sanskrit literature, he says, is from 12th century of Chalukya [King] Someswara III who compiled a book called Manasollasa. “The text documented all the activities that take place in the king’s court,” he says. The text offers an accurate description of training cheetahs to course blackbuck, a practice that was pursued in India up to mid-20th century. He claims that he was able to source at least 350-plus such references across

the subcontinent.

A painting of a cheetah in a rock shelter, Kharvai, Madhya Pradesh, 2500-2300 BCE. From Wakankar and Brooks, 1976. Author’s collection

A painting of a cheetah in a rock shelter, Kharvai, Madhya Pradesh, 2500-2300 BCE. From Wakankar and Brooks, 1976. Author’s collection

One of the contributions of the Mughals to the tome on cheetahs is the vast number of texts and paintings that they were instrumental in commissioning during the era, primarily because of the popularity of hunting as a sport. “Mughal Emperor Akbar is reputed to have had 1,000 cheetahs in his menagerie at one time, and to have collected 9,000 during his half-century reign,” Divyabhanusinh writes in the book. Akbar also participated in the trapping of cheetahs in the wild, and personally bound “a particularly powerful cheetah”. The cat was tamed, and trained to hunt the antelope, deer and blackbuck among others. The book carries several of these paintings that illustrate how the animal hunted, along with the royal entourage.

“During the reign of Maharaja Sir Sayaji Rao Gaekwad of Baroda, a detailed account had been compiled, titled Chityasambandhi Samanya Mahiti [Common Information Regarding Cheetahs].” Also known as the Baroda manual, and intended for restricted circulation within the state administration, the 38-page publication included everything from general information and capture of cheetahs to taming, training and purchase, upkeep, hunting with them, and food.

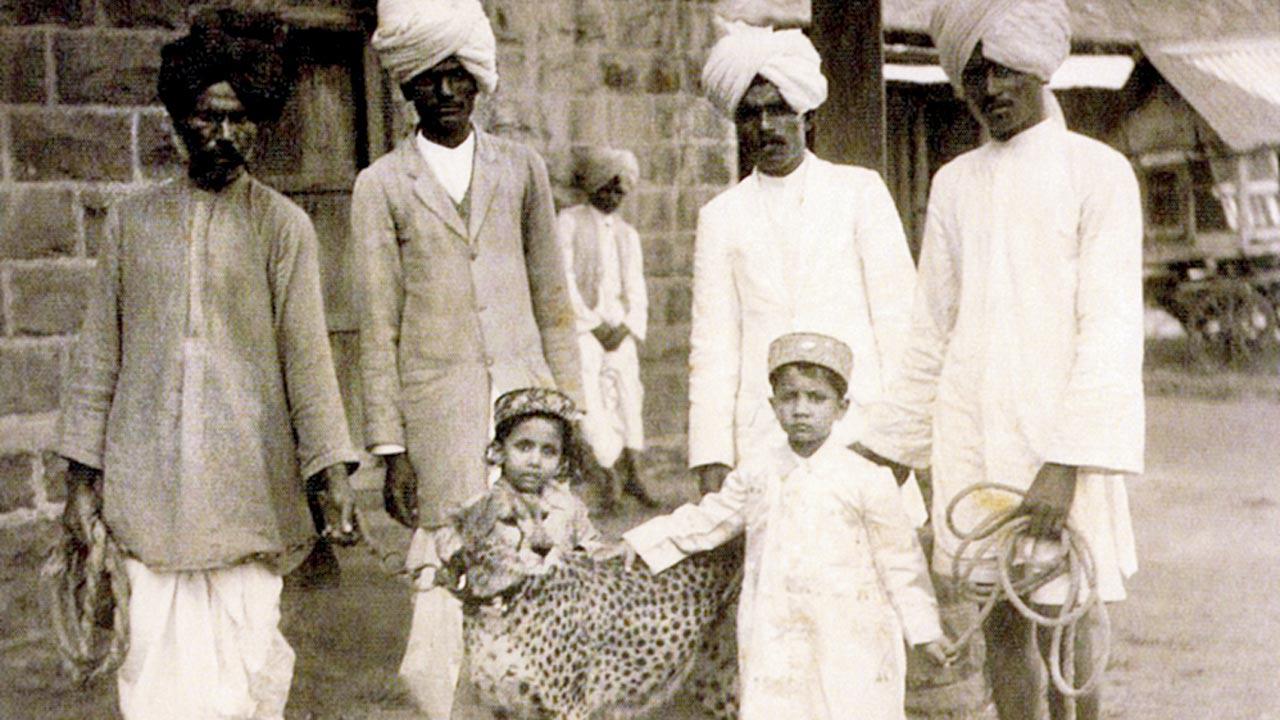

Tame cheetahs were kept with the families of their keepers who looked after them like household pets. This picture was taken by AR Pathan, a court photographer, commissioned to publish the Kolhapur Shikar Album, 1921. Author’s collection

Tame cheetahs were kept with the families of their keepers who looked after them like household pets. This picture was taken by AR Pathan, a court photographer, commissioned to publish the Kolhapur Shikar Album, 1921. Author’s collection

“[From this documentation and pictorial references], I was able to gauge where the cheetahs were found, in what kind of environments they lived, what was their prey base, what was the average life of the cheetah… when you juxtapose these paintings with Irfan Habib’s An Atlas of Mughal Empire: Political and Economic Maps [1982], you can recreate the entire ecology of the cheetah in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries,” he says.

Cheetahs, he suspects, were fairly dispersed during the Mughal period. “The human population during that time was only a hundred million, so that means all the grasslands and scrub jungles, which are the main habitat of the cheetahs were quite intact. Also, if Akbar and his successors were able to capture thousands of cheetahs… it means that they would have been in good numbers.”

Divyabhanusinh

Divyabhanusinh

The animal’s population began to shrink, sometime around the time of Aurangzeb (1658 to 1707). “They [the Mughals] were taking out huge numbers of cheetahs from the wild. Even the female cheetahs were taken away. If you take the mother away from the cubs, who’ll teach the cubs how to survive and hunt in the wild?” Coursing with cheetahs, however, continued as a sport till about 1949-50. Some of the big centres of the sport were Kolhapur in Maharashtra, Bhavnagar state in present-day Gujarat, and Hyderabad. “By 1918, cheetahs were already being imported from African states, because they were close to extinction in India. It was an expensive sport—you needed at least two to three attendants to train a cheetah, and then keep it in a menagerie. The imports stopped by 1939-40 as the second World War loomed. After Independence, when most of the princely states joined the Union of India, they didn’t have the money to import cheetahs, and the sport died a natural death.”

The rise in human population was also a factor in losing the animal. In his book, Divyabhanusinh states that by 1901, the population—according to the decennial census—had increased to 283.9 million, and by 1941 to 389 million. “This would imply a relentless reduction in cheetah habitat,” he states.

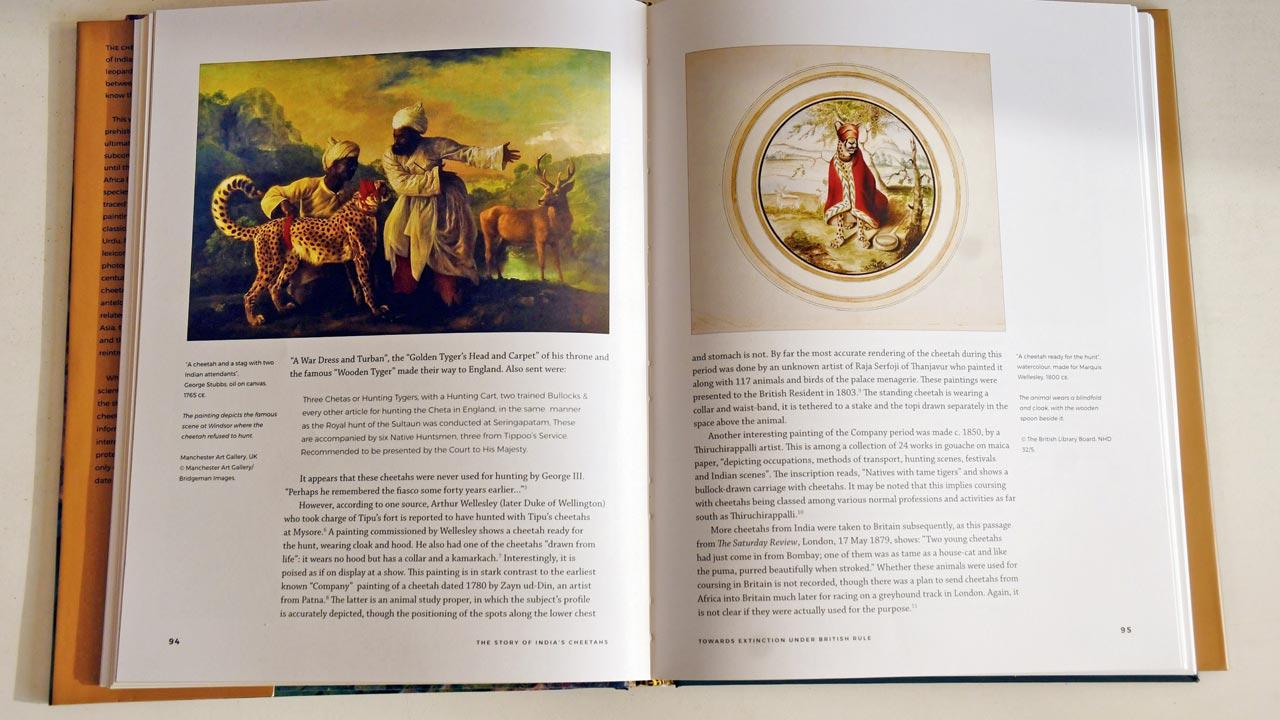

Arthur Wellesley (later Duke of Wellington) who took charge of Tipu’s fort is reported to have hunted with Tipu’s cheetahs at Mysore. The book features a painting commissioned by Wellesley circa 1800 CE, which shows a cheetah ready for the hunt, wearing cloak and hood. Pic/Ashish Raje

Arthur Wellesley (later Duke of Wellington) who took charge of Tipu’s fort is reported to have hunted with Tipu’s cheetahs at Mysore. The book features a painting commissioned by Wellesley circa 1800 CE, which shows a cheetah ready for the hunt, wearing cloak and hood. Pic/Ashish Raje

In the book, he addresses the controversy around bringing back African cheetahs into the wild. The main arguments of the opponents, he says, is that African cheetahs cannot survive in India because of lack of habitat and prey base, and because it is an “exotic species”, introducing such an animal is “ultra vires” of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972. The other argument is that “the project does not find place in the Wildlife Action Plan: 2013-31”. He argues, “To call cheetahs ‘exotic’ is an absurd proposition... they have existed all over India for millennia,” Divyabhanusinh says. He also states in the book that the controversy over African versus Indian cheetah is “infructuous”. On the basis of the information experts have on the cheetah’s behaviour and longevity, the cheetahs appear to “show little or no difference”.

In his estimation, around 200 cheetahs were imported from Africa without tranquilisation or inoculation in the early 20th century by the princes. And they “behaved exactly like Indian cheetahs in captivity, and took to coursing wild Indian antelope just as they would have sprinted after the ones in Africa”. “I’m saying this on the basis of what I have found in the records... I don’t consider myself an expert,” says the cheetah historian. “Cheetah is the only animal in the plains of India to have become extinct post Independence,” he says, “We consider ourselves to be a big power on the world stage... so why should we not be undertaking this exercise?”

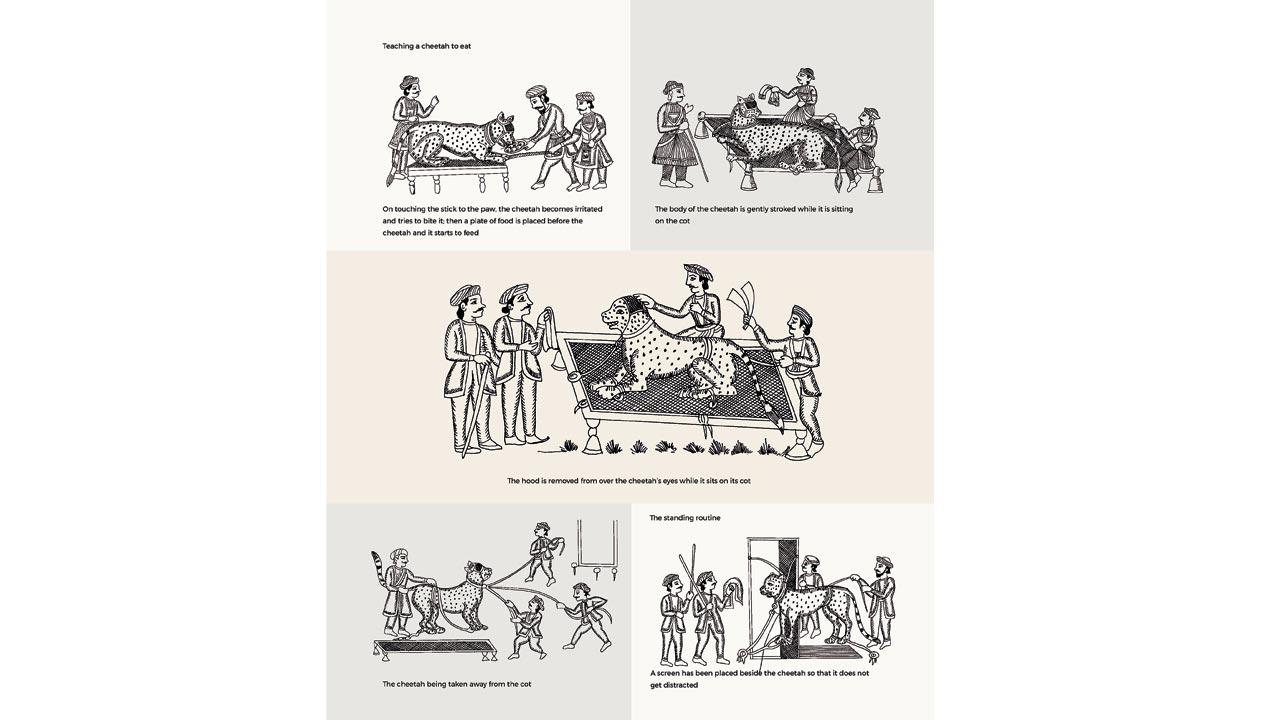

1. Teaching a cheetah to eat: On touching the stick to the paw, the cheetah becomes irritated and tries to bite it; then a plate of food is placed before it; 2. Its body is gently stroked while it is sitting on the cot; 3. The hood is removed from over the cheetah’s eyes while it sits on its cot; 4. The cheetah being taken away from the cot; 5. A screen has been placed beside the cheetah so that it does not get distracted Drawings by Risaldar Kanwar Balwant Singh Panwar, author of the Sa’idnamah-i Nigarin, 1904

1. Teaching a cheetah to eat: On touching the stick to the paw, the cheetah becomes irritated and tries to bite it; then a plate of food is placed before it; 2. Its body is gently stroked while it is sitting on the cot; 3. The hood is removed from over the cheetah’s eyes while it sits on its cot; 4. The cheetah being taken away from the cot; 5. A screen has been placed beside the cheetah so that it does not get distracted Drawings by Risaldar Kanwar Balwant Singh Panwar, author of the Sa’idnamah-i Nigarin, 1904

Two cheetahs, Uday and Sasha, died in less than a month, at the Kuno National Park. While Uday died last Sunday, reportedly succumbing to heart failure, five-year-old female cheetah Sasha died of kidney related ailment on March 27. “At the same time, one female cheetah [Siyaya] gave birth to four cubs last month,” says Divyabhanusinh. For a project of this nature, time and patience is going to be key. “In 1973, when Project Tiger started, the total number of tigers was 1,800; today we have 3,000 of them. Success or failure of this programme [cheetah reintroduction] will depend on how well the forest department of the central and state governments continue with the project, and how efficiently they run it. We have the knowledge and instruments to make it a success,” says Divyabhanusinh, “This is a translocation effort of a major mammal between two developing countries. The whole world is watching. I don’t think we will allow it to fall flat.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!