A new revolutionary school project in the Sundarbans, made using military-inspired construction, points to the need for essential services structures that respond as much to the outside as they do to the purpose they were built for

The walls of a green school being built in Sunderbans North 24 Parganas use lime plaster with natural additives, which adds a water-resistant finish to the facade of the building, preventing water from entering the structure, and offering an additional termite-proof layer

Once this year’s monsoon wraps up, 250 students in one of the world’s richest but most fragile ecosystems, will have a new school to go to. The Sundarbans in West Bengal comprises closed and open mangrove forests, mudflats and barren land, all intersected by numerous tidal streams and channels. That it lies in the delta created by the meeting of three rivers, Brahmaputra, Padma and Meghna, makes it ecologically precarious. Prone to storms and floods, the area faces the adversities of climate change. A report by Mumbai-headquartered agency Observer Research Foundation points to the need for investments in resilient infrastructure.

ADVERTISEMENT

The building of The Rajkumari Ratnavati Girls School is oriented to maximise the prevailing wind and keep sunlight out. PICS COURTESY/VINAY PANJWANI

Heeding the call, Kolkata-based non-profit organisation Ek Packet Umeed is setting up the green school project in North 24 Parganas. In the final stages of completion, it has a structure made using earthbag construction. Built on the principle of the historic military bunker construction technique, the earthbag method ensures endurance in severe flood-prone areas. “The thick bags hold the structure in place and prevents the thick walls from being washed away,” shares Ayush Sarda, founder of the NGO, adding that the ecology of the Sundarbans is changing with the increased involvement of reinforced cement concrete (RCC) structures—a concrete structure carrying embedded steel bars. “Soil in the Sundarbans cannot hold structures made from RCC that are not permanent. Besides, its use increases ambient temperature. To make the establishment more sustainable, we refrained from using any RCC material like asbestos, which is not environment friendly.”

As a woman architect, who was designing the school for female students, Diana Kellogg looked for symbols of strength across cultures and finally settled on the oval shape, which represents femininity and replicates the planes of the sand dunes in Jaisalmer

The walls use lime plaster with natural additives, which adds a water-resistant finish to the facade of the building, preventing water from entering it, and adding a termite-proof layer. “The plinth level has been raised to keep water at bay and a thatched roof is woven and tied to a bamboo framework to encourage the involvement of the local community. When it comes to the interior of the school, it is plastered with earthen clay, adding thermal and sound insulation while making the walls breathable and fireproof,” adds Sarda.

Conceptualised and executed by Jaipur-based studio Earthen Kriya, which specialises in designing natural buildings, the school plan relies on natural resources. “There are six classrooms and two activity rooms. While the classrooms have two large windows each, the activity rooms have a skylight, ensuring maximum natural light consumption. The walls are textured and have round edges, which stimulates children’s cognitive ability and creative thinking,” shares Sarda, adding that the school offering English medium pre-primary and primary education will also double up as a shelter in times of calamity.

Built on the principle of the historic military bunker construction technique, the earthbag method ensures endurance in severe flood-prone areas

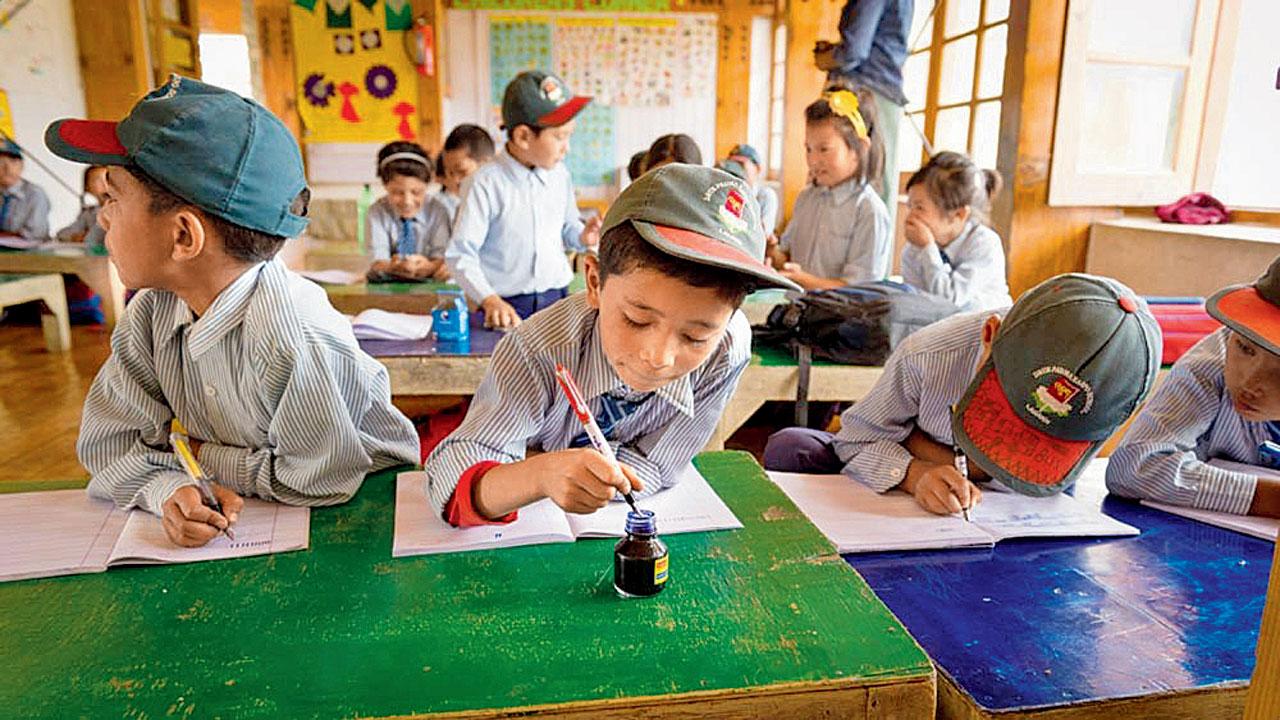

While flooding is a problem in the Sundarbans, Ladakh, a desert located at 3,500 metres above sea level, faces a shortage of water. In 1992, the 12th Gyalwang Drukpa initiated the Druk White Lotus School project to provide comprehensive modern education combined with the traditional value system to local Ladakhi children. To not burden the scarce water supply, the school was designed with ventilated improved pit (VIP) latrines. The solid and liquid human waste is deposited into a pit and the aeration in the VIPs keep odour and fly nuisance under check. “Our students and staff rely on water only to wash their hands. The waste is collected and a year later, used as a manure in our orchards,” shares Mingur Angmo, principal of the school located in Shey village of Leh.

Constructed in fits and starts over a decade, the award-winning school, which also made it to the climax of Aamir Khan’s 3 Idiots, started operations as a nursery courtyard in 2001 with 88 students, and gradually added more classrooms, facilities and hostel buildings. It currently teaches 870 students, aged four to 16, from preliminary to class X. Of these, 250 students reside in the hostels.

In its bid to maximise the use of natural resource, the school in Ladakh has installed solar panels

“Designed by architects and engineers from Arup Associates, the school structure employed local building techniques and materials coupled with new-age environmental design to make it effective in the extreme climatic conditions of Ladakh. While the roof and flooring are of wood used from local trees, willow and poplar, granite and local stones have been used for the walls. To reduce the need for a heating system, we have relied on the trombe wall technique, a type of technology to passively heat a building. The exterior parts are painted black, and glazed. This sort of facade helps trap the heat,” adds Angmo. Since Ladakh is prone to earthquakes, the school, initially built to sustain a quake of magnitude of 5 on a Richter scale, is being refurbished so that it can sustain an earthquake of up to 8 in magnitude. Additionally, the school building has an orientation of 30 degree South-East so that it receives maximum natural night.

In 1992, the 12th Gyalwang Drukpa initiated the Druk White Lotus School project to provide comprehensive modern education combined with the traditional value system to local Ladakhi children. PICS COURTESY/DRUK WHITE LOTUS SCHOOL

At the other extreme end of the temperature scale is Jaisalmer’s heat. New York-based Diana Kellogg Architects, who was commissioned by American NGO CITTA, which works for women’s development across health and education in India and Nepal, devised the plan for The Rajkumari Ratnavati Girls School. Using local materials like Jaisalmer sandstone, it incorporates heavy use of recycling. Recycled ceramic tiles were used for the roof, and the interiors of the classrooms were lime plastered. Since the school is housed in desert-like conditions, the design team followed the ancient water harvesting technique to maximise rainwater harvest.

“How do you keep the students cool and comfortable while they study, without employing air conditioning? The building is oriented to maximise the prevailing wind and keep as much sunlight out as possible. The team also employed solar panels for lights and fans,” says founder and principal architect, Diana Kellogg.

As a woman architect who was designing the school for female students, she looked for symbols of strength across cultures and finally settled on the oval shape, one which represents femininity. The shape is also meant to replicate the planes of the sand dunes in Jaisalmer. “The elliptical shape of the structure helps us easily include aspects of sustainability, creating a cooling panel of airflow, in addition to passive solar cooling in an area where temperatures peak close to 120 degrees Fahrenheit,” says Kellogg, adding that the school took 10 months to complete. “My goal was not to disturb the dunes as natural works of art but to be inspired by the forces of nature. The desert is inherently mysterious and eternal. I wanted to recreate this metaphysical expression and embrace primal existence,” shares Kellogg, adding that the obvious challenge with building this school was distance and assimilation to a different culture.

“In India, they have an expression called jugaad, which loosely translates to makeshift. To me, this spirit is the only way to come close to creating magic, and ultimately art instead of architecture,” she adds. Currently, the building stands alone in the midst of the desert. Planned as part of the Gyaan Centre, it is soon to have an accompanying structure which will house a women’s cooperative, and the Medha Hall, an exhibition space. Together, the three ovals will resonate with the formulation of an infinity.

With inputs by Nidhi Lodaya

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!