The Bloomsbury Handbook of Indian Cuisine is one of the most definitive and comprehensive guides to Indian cuisine. Here’s an excerpt

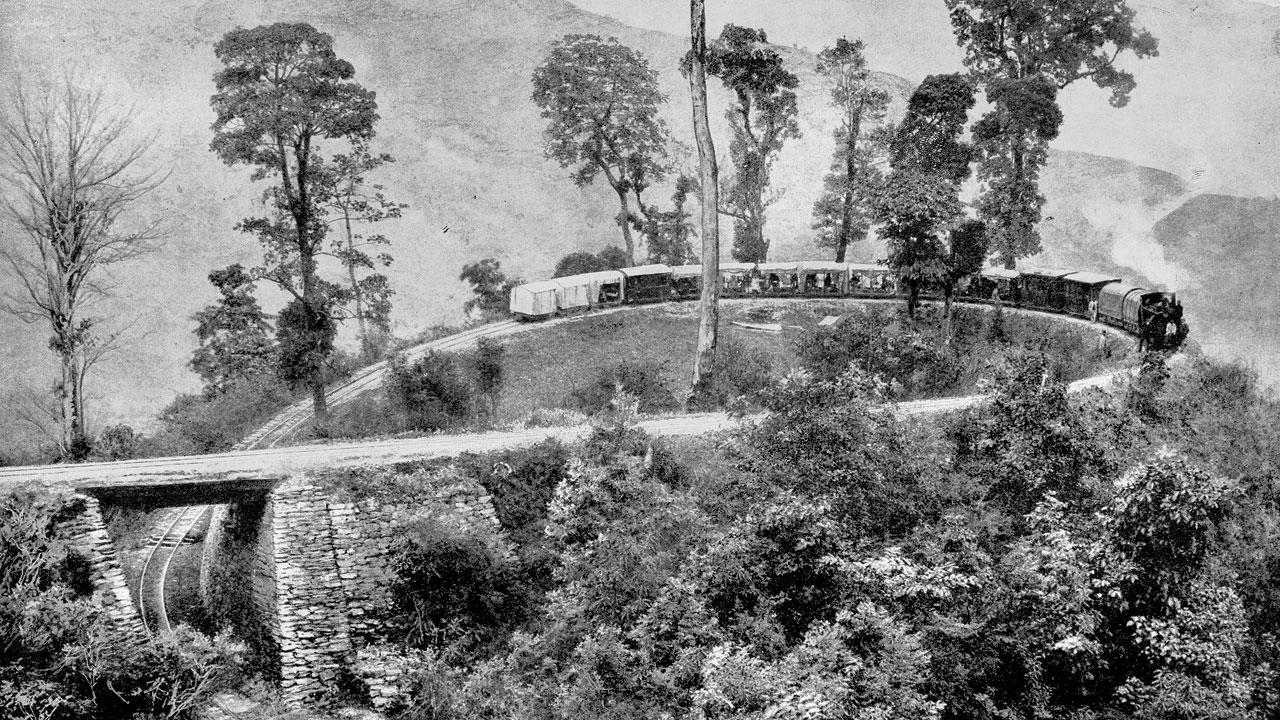

Antique photograph of the British Empire: The loop, Agony Point, Darjeeling Railway

At the beginning of the twentieth century, India had one of the largest railway networks in the world. The first freight train was built in Madras in 1837 and the first passenger train began a short run from Bombay to Thane in 1853. After India became a colony of the British crown in 1858, the development of railways became a priority for the British, for both economic and military reasons.

ADVERTISEMENT

The first passenger trains were intended for the use of the British, although they quickly became popular among Indians too. In the early twentieth century, long-distance trains such as the Grand Trunk Express, the Frontier Mail and the Deccan Queen had luxurious dining cars with butlers, chefs, uniformed waiters and à la carte menus. The catering was undertaken by G.F. Kellner & Co. in the east and northwest (acquired by Spence & Co. in 1929); Spence & Co. Ltd. in the south; and Brandon in central India. The food combined European and Indian influences, especially Anglo-Indian, Bengali and South Indian. Western dishes might include thick or clear soup, fried fish or minced cutlets, roast chicken or mutton, and for lunch, a choice of curry and rice or the previous night’s roast. The trains carried live chickens while mutton was picked up at stations en route.

As late as 1929, these trains had separate dining cars for Indians. In trains without restaurants, First-Class passengers could telegraph their order beforehand and it would be collected at the next station. Important trains halted for breakfast, lunch or dinner in one of the several restaurants on the platform. Starting in 1936, the famous Frontier Mail train (now the Golden Temple Mail), plying between Mumbai and Amritsar, was the last word in luxury with showers and even a steam room. Its extensive menu included roast chicken, Madras mutton curry, chicken cutlet and the iconic Railway mutton curry, which eventually became an item in hotels. This milder version of a classic mutton curry was not too spicy and blended the taste of both Indian and English spices. Railway mutton curry was served with rice, bread or dinner rolls.

Many Indian passengers carried their own food, as they still do today. There already existed a tradition of packing for long journeys food that would keep for several days–dry snacks such as parathas, chaat, bhel puri and theplas. Sharing food with one’s fellow passengers was popular and some writers have noted that this was their first introduction to the food of other regions. The Railways allowed vendors to sell food on platforms, a practice that continues today. The refreshment rooms at stations began offering food and had three separate rooms for Europeans, Hindus and Muslims. Some hotels set up food stalls near railway stations. People could buy cups of tea from vendors at platforms along the way. The Indian Tea Association, founded in 1881, saw the Railways as a potentially large market and supplied tea and kettles to contractors at main junctions. The tea served used more milk and sugar than traditional English tea to meet Indian tastes.

After Independence, management was taken over by the state-owned Indian Railways. Dining cars continued to operate but they were expensive and only survived on a few lines. So the Railways began operating pantry cars on long-distance routes, offering freshly cooked food to passengers at their seats. First class passengers could order meals from bearers by telegraph through bearers. Depending on the service, meals were served on chinaware or iron trays. Breakfast could be an omelette or a vegetable curry with toast, jam and tea. Lunch and dinner were often chicken or vegetable curry with rice, chapatis and pickles. Certain trains were famous for specific dishes; for example, the Gitanjali Express’s (Mumbai-Kolkata) chicken cutlets.

Today you still find dining cars, good linen, bars, excellent service and even spas on luxury trains such as the Deccan Odyssey. On trains like the Shatabdi Express, a series of fast passenger trains that run between major cities, and the Rajdhani Express that run between Delhi and state capitals, food is served in sectioned plastic trays with each dish packed separately in an aluminium foil dish with a paper lid. Rotis are rolled up and foil packed and pickles are bubble packed. There are always vegetarian and non-vegetarian options, with paneer and chicken curry being the differentiating factor. For dessert, ice cream, yoghurt and sometimes rasgullas are brought around in tubs. The food always has a signature spicing depending on the departure station; for example, the Rajdhani Express has Bengali-type food on its Kolkata-Delhi run and Delhi-style food on the Delhi-Kolkata route.

Breakfast is mainly bread, butter, omelette or a vegetarian cutlet with fried potatoes and peas and sometimes poha (flattened rice) or paratha. Tea and coffee are served in a package along with hot water in a flask. Hawkers at railway stations sell local specialities. Today passengers use phone apps to have food delivered from railway catering companies at the next station.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!