A new book that offers a fresh account of the controversial political assassination of the Mahatma, unearths a complex plot that involves a Partition refugee, a princely state and a Hindu political party

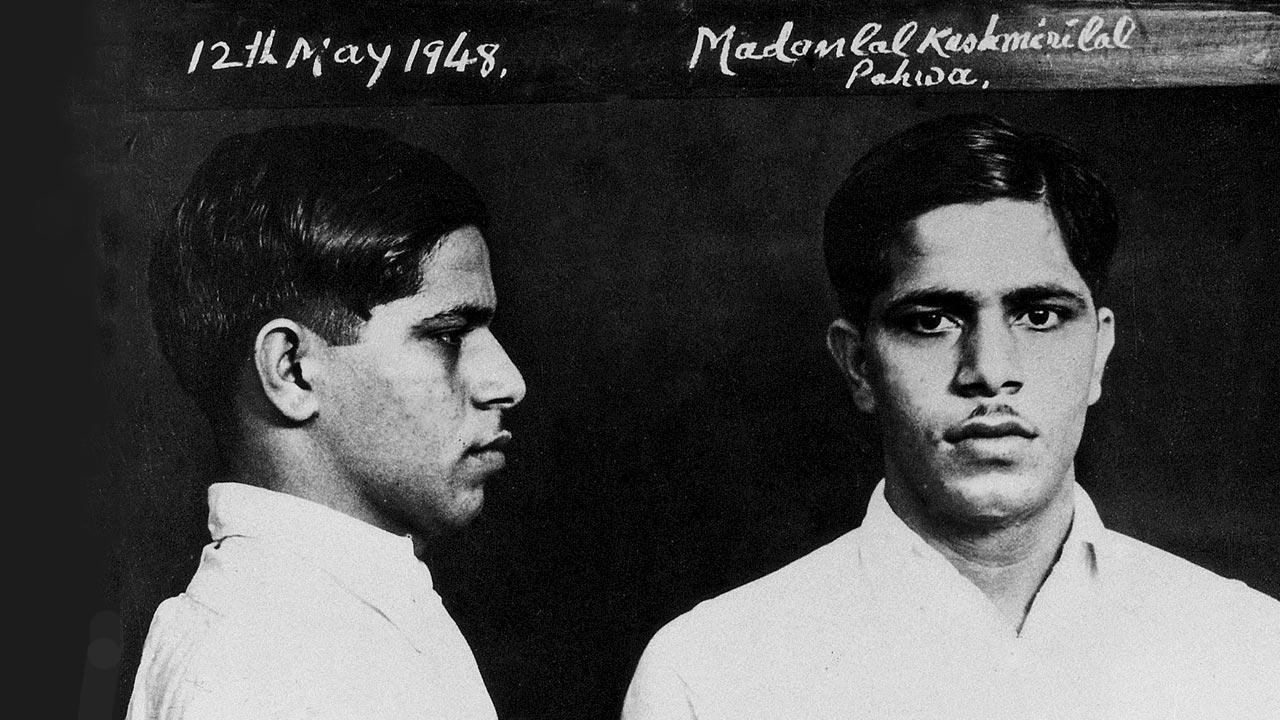

Madanlal Pahwa, a refugee from Pakistan, had made a failed attempt to assassinate Gandhi on January 20, 1948. Pics/Getty Images

History can sometimes be unforgiving. But, more often than not, it is plagued by amnesia. Madanlal Pahwa is a product of this affliction. In Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination story, there appears to be only one anti-hero—Nathuram Godse, the man who pumped three bullets into his frail body at Birla House, Delhi, on January 30, 1948. Only 10 days before this incident, 20-year-old Pahwa, a refugee from Montgomery (today, Sahiwal) in Pakistan, had set off a guncotton slab during a prayer meeting at the same venue, in an attempt to kill the Mahatma. “I think apart from [author] Manohar Malgonkar and [political psychologist and social theorist] Ashis Nandy, who wrote in some detail about Madanlal, his story is relatively unknown. He had witnessed the horrors and violence of the Partition, before he came to Bombay, and became a willing foot-soldier to kill Gandhi,” shares journalist-scholar Priyanka Kotamraju, in a video call with mid-day.

ADVERTISEMENT

In a new book, The Murderer, the Monarch and the Fakir (HarperCollins India), which Kotamraju has co-authored with investigative journalist Appu Esthose Suresh, the duo shine new light on Pahwa, while also offering a fresh account of the events leading up to one of the most controversial political assassinations in contemporary history. Suresh’s interest in Gandhi began while he was a student at St Stephen’s College, Delhi. The college had a Gandhi Study Circle (GSC), one of the oldest student societies, which he says was “practically defunct” when he joined. “At the time, I remember having only two broad ideas about Gandhi’s assassination—first, that Godse killed Gandhi, because of his pro-Muslim approach. The second, was that RSS [Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh] was responsible for the incident,” he says. These ideas slowly evolved as Suresh, who revived the society, came in close contact with other Gandhian scholars and researchers, prompting layered investigations about the leader’s life, including the fact that there had never been any proof to implicate the RSS in his murder.

The hand gun used in the assassination of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869 - 1948), in 1948. A senior bureaucrat had told Appu Esthose Suresh that the gun had come from the Alwar armoury

The hand gun used in the assassination of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869 - 1948), in 1948. A senior bureaucrat had told Appu Esthose Suresh that the gun had come from the Alwar armoury

Later, as a reporter, in 2012, one of his sources, a third-generation bureaucrat told him that he had “seen a picture of the Maharaja of Alwar, whose nails had grown rather long, in house arrest imposed by then Home Minister Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel”. His source, Suresh tells us now, believed that the gun that killed Gandhi came from the Alwar armoury. That was an unusual revelation. “I went back and checked as many references as possible, but I couldn’t find this story.”

It’s while chasing this story for the daily broadsheet where he worked, that the idea of researching this book came by. Kotamraju, who was a colleague of Suresh’s, joined him in the research in 2018.

For the book, the authors have dipped into previously unseen intelligence reports and police records, “haphazardly scattered” at the National Archives of India and the Nehru Memorial Museum Library. Another important source was the report of the Jeevan Lal Kapur Commission, instituted nearly 20 years after Gandhi’s assassination, to carry out an inquiry into the conspiracy. As the plot unravels, we are introduced to a wide cast, including Godse and his brother Gopal, Narayan Apte, Vishnu Karkare, Digambar Badge, Shankar Kistayya, Pahwa, nationalist leader Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, Hindu leader and doctor Dattatreya Parchure and then Prime Minister of Alwar state, Dr Narayan Bhaskar Khare, all of whom are in complex ways linked to the assassination plot, which is likely to have been scripted at a meeting on August 8, 1947.

Appu Esthose Suresh and Priyanka Kotamraju

Appu Esthose Suresh and Priyanka Kotamraju

Pahwa, who lost his aunt in the bloodbath that followed the Partition, was an outsider of sorts. His squad, comprising the Godse brothers, Apte, Kistayya and Badge, never divulged too much about their whereabouts or the people they were meeting. That he was the only non-Marathi speaking person, meant he rarely ever was able to pick up on the conversations. “Madanlal’s story is very important in this book, because he represents the whole process of ‘othering.’ While his co-conspirators were feeling equally charged and revengeful about what had happened to their people [the Hindus in the Partition], it was only Madanlal who really suffered that kind of violence,” says Suresh. Kotamraju adds, “This is why if Madanlal’s attempt to kill Gandhi had been successful, he would have been the perfect scapegoat. He perhaps had all the reasons to commit the crime.” He was also the only person to see the first plan (January 20, 1948) through—three of the conspirators fled the scene in a “green taxi,” while Badge remained quietly in the prayer meeting. “Godse feigned sickness during this attempt. Come to think of it, if Madanlal and Gopal had killed Gandhi then, we probably would have never known Godse,” she says.

Other leads that the authors investigate are the roles of the princely state of Alwar and Veer Savarkar, who was acquitted for lack of evidence in the case. They take great pains to examine why a princely state, would want Gandhi killed. One of the clues, they share, is in a letter that Gandhi wrote to Gandhian economist Shriman Narayan on December 1, 1945, while on board a train to Calcutta, where he shares his position on the princes and their lands, which was far from flattering. Subsequent letters and a meeting with Lord Mountbatten made his views even clearer, where he spelled out in plain terms that the princes were a “creation of the British”; he wanted them to delegate power to the “people” in free India. The Hindu Mahasabha, co-founded by Savarkar, believed that the princely states were the custodians of the Indian culture, and saw the Mahatma as an “anti-national”. “During research we found interesting evidence on the role of Alwar state, which was unfortunately never pursued [by the investigators],” says Suresh, who is currently Senior Atlantic Fellow at the International Inequalities Institute, London School of Economics and Political Science. “If you have to rank Gandhi’s foes, I would say that since 1944, the princely states were his No. 1 arch-enemies. They were a very powerful lot, and that is why they could have been protected. So, if there’s something that needs to be reinvestigated, it’s the role of the economic and power elite [in the assassination of Gandhi],” says Suresh.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!