Chasing a hazy address in Girgaum, mid-day tries joining the dots that make up the story of Mumbai and Raja Ravi Varma

Ganesh Shivaswamy at the Hasta Shilpa Heritage Village with the artefacts of the Ravi Varma Press. Pic/Kushal Raheja

The story of an institution that cast a long shadow on Indian society for over a century, but whose physical presence has all but disappeared, is the stuff of urban legend. Yet in the case of the Ravi Varma Press, which stood tall in Girgaum in the late 19th century, it is the truth.

ADVERTISEMENT

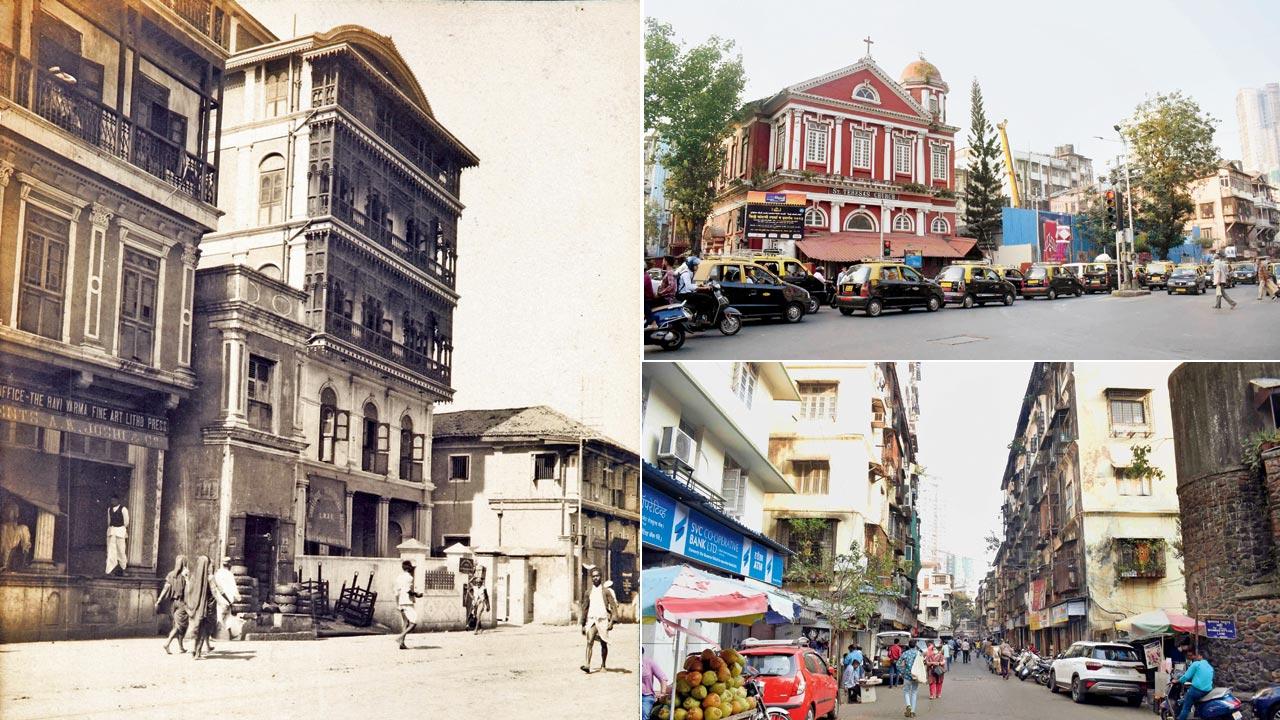

In the second volume to his tome on the legendary painter, advocate and author Ganesh Shivaswamy lists the many distributors the Press engaged, such as Thacker and Co. and Soundy & Co., identifying the very neighbourhoods they operated out of. The location of the lithographic press, on the other hand, remains uncertain—though it was known to have been in and around Girgaum, “in the house of an unidentified businessman opposite the Portuguese Church in Girgaum, while another refers to it being ‘located in the extensive buildings on the Kalbadevi Road’.” A third reference in Shivaswamy’s Raja Ravi Varma: An Everlasting Imprint mentions a leasehold land at Old Number 216 and New Number 1676, Proctor Road. When mid-day went on a quest to find these spots, we found fast-moving city life and cosmopolitanism—the very things that perhaps drew Ravi Varma (1848-1906) to Mumbai, then Bombay Presidency.

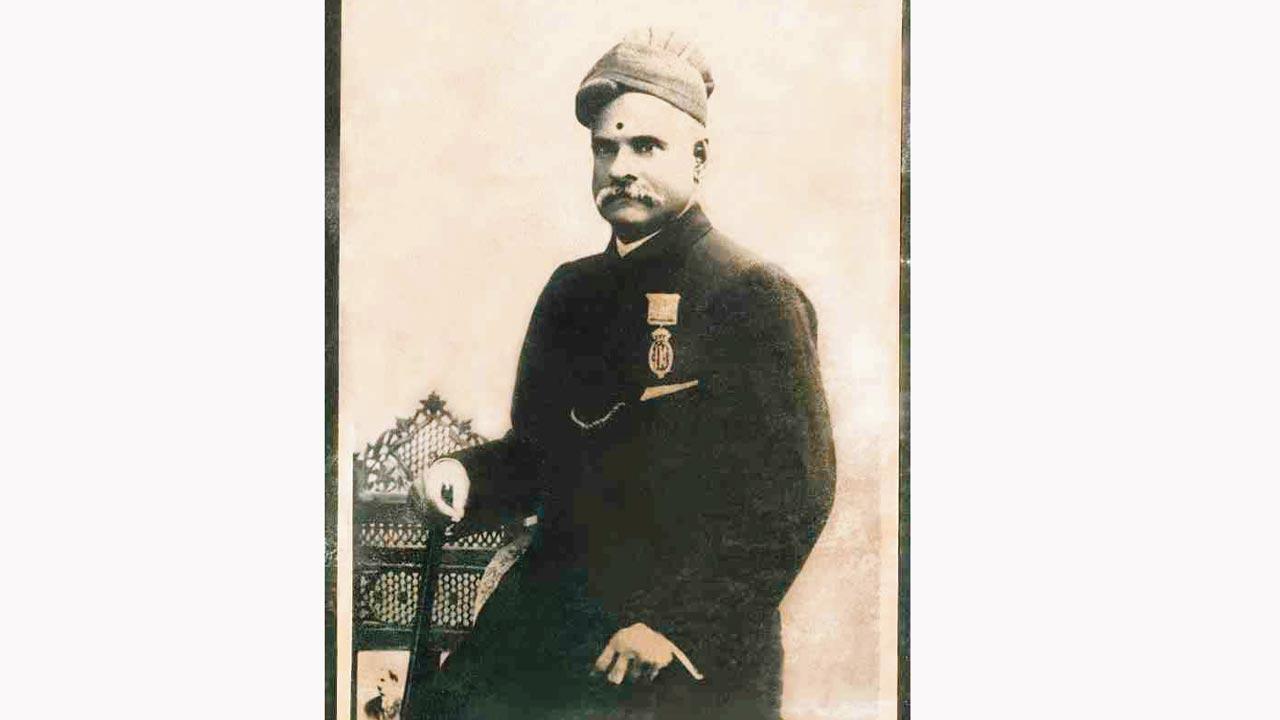

Raja Ravi Varma. Pic/Facebook

Raja Ravi Varma. Pic/Facebook

Shivaswamy’s research and the scholarship of academics like Priya Maholay-Jaradi paint a vivid picture of Ravi Varma’s life in then Bombay and the people who were recurring characters in it. By tracing the journey of the press set up in his name, and unveiling who his patrons were, they also transport us to a Mumbai of the past—where the artist captured the imagination of the elite and the public, drawing crowds to exhibitions and rubbing shoulders with its tastemakers and polity.

Ravi Varma’s reputation reached Mumbai much before he did, and the work of the Ravi Varma Press ensured that it lived on for years after his death,” Shivaswamy said at the recent launch of his latest book. Born in 1848 at Kilimanoor Palace into the royal family of the erstwhile princely state of Travancore, Ravi Varma first emerged as an artist in 1870. Between 1880 and 1990, a number of events took place, prompting him to set his eyes on the city.

Priya Maholay-Jaradi. Pic Courtesy/Manish Chauhan; (right) Ramavarma Thampuran

Priya Maholay-Jaradi. Pic Courtesy/Manish Chauhan; (right) Ramavarma Thampuran

In 1881, Bombay Governor Sir James Fergusson wrote to T Madhava Rao, the then Dewan of Travancore, seeking a copy of the painting Nair Girl Tuning a Fiddle. Rao suggested to Ravi Varma that he should send a few select works to Europe to have them oleographed (a print textured to resemble an oil painting), telling him this would be in service of the country. The Dewan also facilitated Ravi Varma’s introduction to the Baroda Court of Sayajirao Gaekwad III; in 1891, paintings of Puranic subjects from Hindu mythology commissioned by Gaekwad were exhibited in Bombay, earning the artist great fame.

As Maholay-Jaradi documents in her book Parsi Portraits from The Studio of Raja Ravi Varma published by The KR Came Oriental Institute, the paintings reportedly “produced quite a sensation” for their depiction of subjects from the Indian epics. Crowds of people from different parts of the Bombay Presidency are said to have attended the exhibition. Shivaswamy highlights a newspaper article published in the wake of the exhibition, recommending that Ravi Varma have his works photographed and sold at a moderate price, so more people can access them.

Photograph of the Raja Ravi Varma Press in Bombay. Pic Courtesy/P&G collection, Karlsruhe-Berlin; Conjectured locations of the Press at Girgaum’s Portuguese Church and Proctor Road. Pics/Sameer Markande

Photograph of the Raja Ravi Varma Press in Bombay. Pic Courtesy/P&G collection, Karlsruhe-Berlin; Conjectured locations of the Press at Girgaum’s Portuguese Church and Proctor Road. Pics/Sameer Markande

These suggestions to photograph his works and make copies of them inspired Ravi Varma and his brother C Raja Raja Varma to set up their own lithographic press—sowing the seeds of a legacy that lasted a century. The artist-brothers counted among their friends two key figures of the city, Dadabhai Naoroji and Justice Mahadev Govind Ranade, whose portraits Ravi Varma famously made. Shivaswamy writes that Ravi Varma consulted Naoroji and Ranade, who suggested that he establish the Press with a partner, the Bombay industrialist Govardhandas Khatau Makhanji.

“The reason why many great individuals in the city had a deep impact on him is that they were each engaged in larger issues. These individuals were also instrumental in the revival of important cultural icons and festivals, like Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and Ganesh Chaturthi. Their work brought people together, and they also recognised Ravi Varma’s potential as an artist,” Shivaswamy tells mid-day.

Indira. Chromolithograph from the Ravi Varma Press, Bombay. Pic Courtesy/Girish Prabhu

Indira. Chromolithograph from the Ravi Varma Press, Bombay. Pic Courtesy/Girish Prabhu

Simultaneously, Ravi Varma began to draw in a growing number of patrons, which would go on to include industrialists such as Nasswerwanjee M Petit and colonial administrators such as Charles Pritchard, among numerous other men, women, and children. “If the Varma brothers were drawn to Bombay’s multi-cultural ethos, Bombay-based patrons were equally enticed by their art practice,” says Maholay-Jaradi, Convenor of the Art History Minor, National University of Singapore. This development, coupled with the establishment of the Press, signalled the moment when Mumbai became his base. The brothers also set up a studio in Girgaum. She writes that this studio facilitated direct meetings between the artist and his patrons. Significantly, Ravi Varma’s appreciation of Bombay’s cosmopolitanism may be attributed to his practice which was field-intensive, as opposed to being strictly studio-based, she says.

“In other words, he travelled widely within and between cities to create numerous on-the-spot studies, while his artist-brother and manager C Raja Raja Varma maintained copious notes of their travels through two sets of diaries… These writings tell us that although Bombay was one station in a multi-city network through which the artist brothers travelled frequently for study, work, and leisure, its vibrant character never failed to inspire their art,” the academic adds.

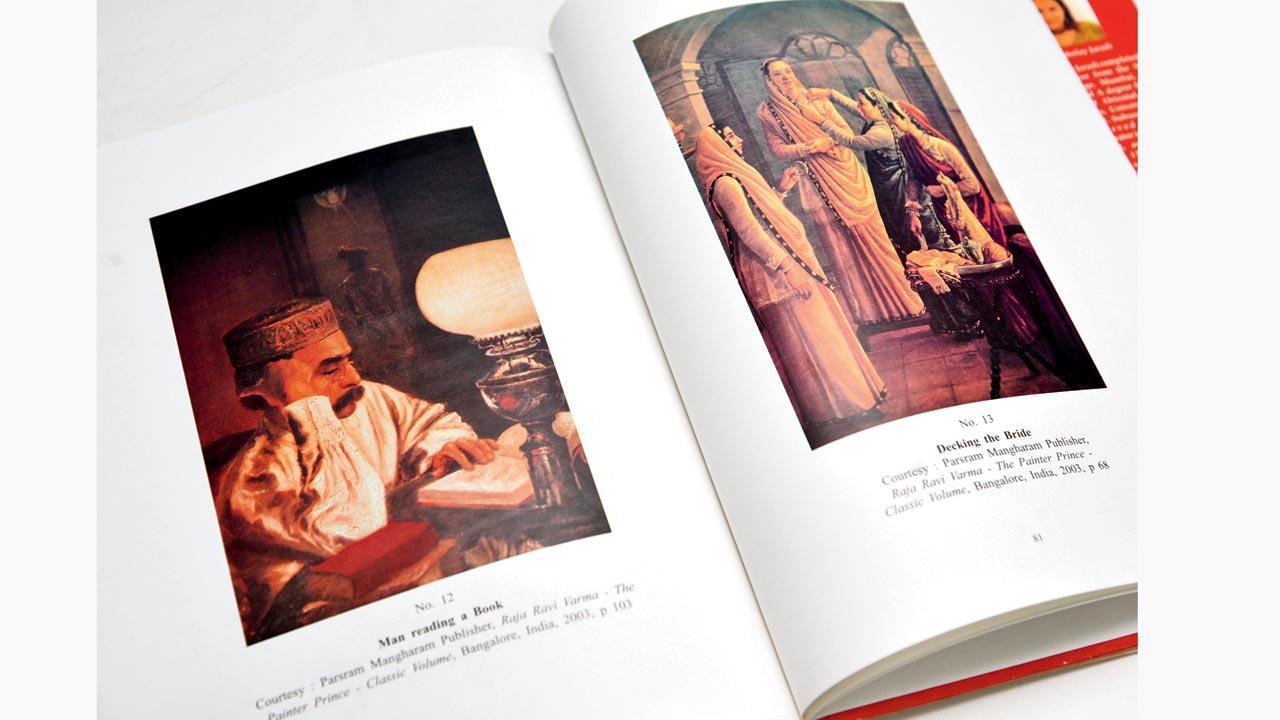

Pages from Parsi Portraits from The Studio of Raja Ravi Varma, published by the KR Cama Oriental Institute. Pic/Satej Shinde

Pages from Parsi Portraits from The Studio of Raja Ravi Varma, published by the KR Cama Oriental Institute. Pic/Satej Shinde

In a black-and-white photograph from 1894, originally published in an Oxford University Press India book, Ravi Varma and his brother are captured at work: The duo stand at their easels with other paintings in the backdrop, as a turbaned subject poses for them. The details recorded by the Prince of Aundh, Bhavanrao Pant Pratinidhi, during his interactions with the artist lets us in on his routine, too: about how Ravi Varma began working at 7.30 am in the morning, putting in seven to eight hours even on days when he travelled.

Mumbai held promise for the artist owing to its smaller, urban offerings as well—such as the availability of newspapers. Shivaswamy recalls a diary entry about how Ravi Varma and his peers visited a home where the new gas lamp was installed, a thing of wonder at the time. “It wasn’t just about meeting grand personalities and influential individuals—the allure of the city lay in the smaller things too,” the author explains.

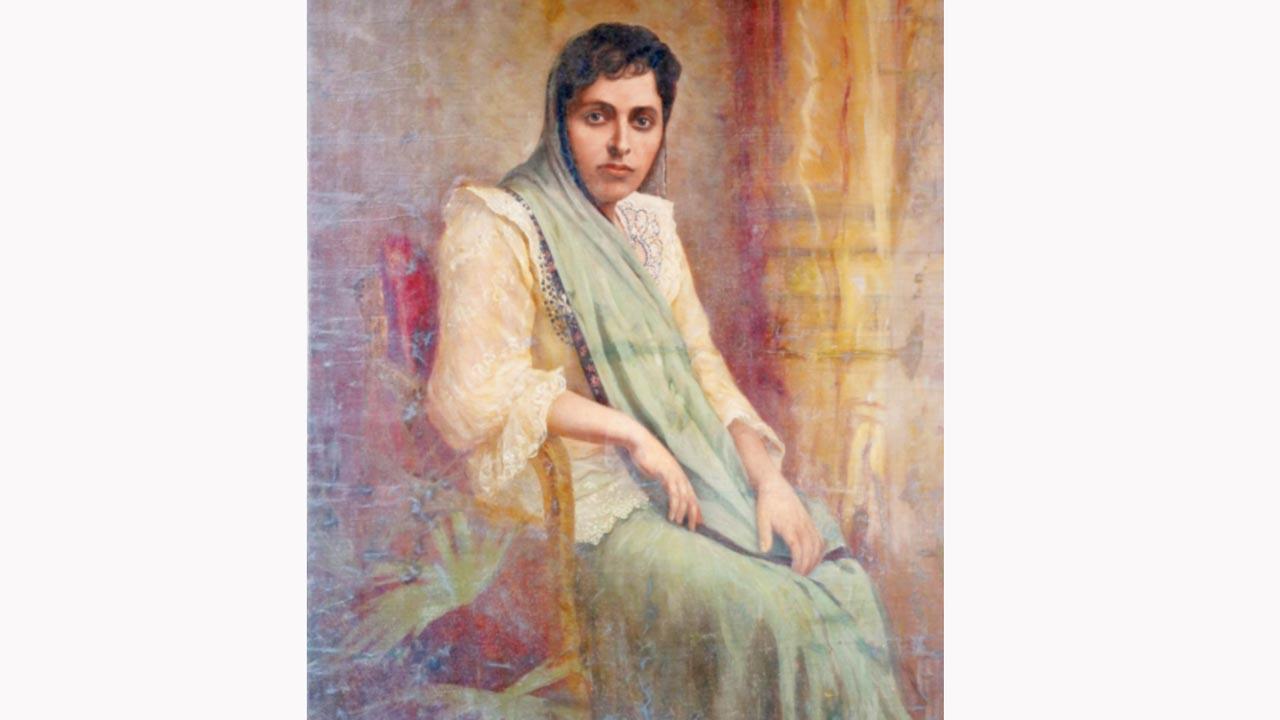

Parsi Lady by Raja Ravi Varma. Pic Courtesy/Kilimanoor Palace Trust, Kilimanoor

Parsi Lady by Raja Ravi Varma. Pic Courtesy/Kilimanoor Palace Trust, Kilimanoor

The city’s status as a port catalysed the everyday workings of Ravi Varma’s studio as well as the setting up of the Press. “Resources like glass, paper and lithographic ink came from Europe, as did the equipment of the Press,” says Shivaswamy. Maholay-Jaradi writes that European art had an educational significance for the brothers, who purchased art books and prints and copies. “An added advantage in the prolific production of portraits at the Bombay Studio was the easy availability of art materials in the city’s markets,” she writes; this material was both imported and bought locally, from businesses like Messrs Thacker & Co., and Hussainally’s. C Raja Raja Varma even writes about visiting the venture of a DB Dinshaw for gilt frames.

Raja Ravi Varma’s journey illustrates how the cultural authority, progressivism and cosmopolitanism of a city could mould an artist in pre-Independence India. Though his Press may be best known for images and iconography of Hindu deities and personalities from epics, Ravi Varma also painted themes from other faiths and cultures.

Maholay-Jaradi outlines how the city attracted merchants, traders, skilled craftsmen, and professionals from diverse religious, racial, and ethnic groups who mingled with indigenous groups and earlier migrants. “Bombay’s multi-cultural offering was well-suited to Varma’s practice. He tapped into diverse registers of the city’s population to study and sketch varied facial types, costumes, cultural habits, and domestic settings. Neighbours, friends, and visitors to his studio posed as models,” she explains.

In particular, he observed the Parsi community intimately: Maholay-Jaradi writes that the Parsis were “acquiring new social and economic positions in the colonial society due to their rapid westernisation and commercial prosperity”. As an emerging class of art patrons, Ravi Varma was one of the Indian portraitists and salon artists they offered commissions to. Parsi patrons were brought to his doorstep by his prolific presence at exhibitions by Art Societies in the country—where talent was recognised and encouraged—and vibrant art journalism. These are also the factors that propelled his nation-wide reputation.

Given that Bombay was a fast-growing Presidency town, “British colonial administrators and community leaders turned their attention towards expanding the city’s civic infrastructure and amenities in the form of schools, hospitals, libraries, charitable institutions, and places of worship. These new public and philanthropic projects translated to portrait commissions for artists, including Varma. As is widely known, portraits serve to document and memorialise their sitter-subjects, in this case founders, sponsors, and donors who contributed to the making of nineteenth century Bombay,” Maholay-Jaradi notes. The artist’s work continues to hangs across magnificent corridors and hallways of colonial-era buildings in Mumbai thanks to his close engagement with the city, she says.

Notably, Ravi Varma’s last unfinished painting was Parsi Lady, which was part of the collection of the Kilimanoor Palace Trust. Having sold the press to the German Fritz Schleicher, under whose proprietorship the Press grew and turned great profit, the brothers took Ravi Varma’s unfinished works back to Kilimanoor, says the artist’s descendant Ramavarma Thampuran. “But because of his ailments and the untimely demise of his beloved brother C Raja Raja Varma, he could complete only a few of these,” he adds. The painting was restored and unveiled in April this year on the artist’s 175th birth anniversary.

Ravi Varma also benefited from his engagements with Parsi and Marathi theatre, where he met prospective patrons and subjects, as well as took inspiration.

“Anthropologists and academics have found similarities between Ravi Varma’s paintings and Marathi theatre backdrops—this is where the influence is discernible,” Shivaswamy says, adding that the vernacular theatre also borrowed from the artist. This is evident in the style and costumes worn by the iconic stage actor and singer Bal Gandharva.

Ramavarma Thampuran draws our attention to another key face of the Bombay Presidency who crossed paths with Ravi Varma—Dadasaheb Phalke. “Phalke was one of Ravi Varma’s employees at the Press before starting his own ventures. Later, he became one of the artist’s most trusted companions. Ravi Varma knew of his friend’s passion for filmmaking,” Thampuran says. Shivaswamy’s book mentions that Phalke’s first assignment was performing photo-litho transfers. Ravi Varma’s influence on the director especially comes across in a lobby card created for the 1937 film Gangavataran, whose design closely resembles the composition of a chromolithograph.

C Raja Raja Varma’s diary lets us in on the brothers’ proximity to the city’s political class; on the eve of a general election of the Municipal Corporation, the brothers were reportedly anxious to know the results, as their friends and acquaintances were among the contesting candidates. Ravi Varma had made portraits of many members of the Bombay Presidency Association—from merchant Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy to Sir Dinshaw Petit.

Even at the height of the plague epidemic, the brothers found shelter. “His contacts and meticulous organisation of schedules, possibly handled by C Raja Raja Varma alone, helped the Varma brothers to get accommodation in mansions of wealthy men on the outskirts of the city when Bombay was infested with the plague,” Maholay-Jaradi writes. Given that they enjoyed the benevolence and support of wealthy and influential families, which enabled them to live at addresses like Setna Lodging in Girgaum, the brothers never bought a home in the city.

The first ever chromolithograph the Press published, in July 1894, was titled The Birth of Shakuntala. Sized 90 cm x 50 cm, it was priced at the significantly large sum of R6. Merely four years later, amid the plague epidemic and anti-British agitation, the Press was first shifted to Ghatkopar, and then to Malavli station in Lonavala. Over the course of a century, even as the institution’s ownership changed, it furthered Ravi Varma’s intent to democratise art, making it available to those outside elite circles.

In a memory documenting their beautiful voyage on an ocean liner, C Raja Raja Varma rues that the artist-brothers couldn’t cross the “kaala paani”. “To them, the port city was a threshold to what could have been, but never was,” Shivaswamy concludes.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!