Indian men, with all their shades of masculinity and machismo, are now under more scrutiny than ever before. A new TV show looks at Indian masculinity in flux and crisis while four documentaries released last week reveal the aggression, social and sexual anxieties in men to be considered ‘man enough’. Where does the Indian male stand in liberalised India, and what purpose does this attention on him serve?

A few years ago, when author Aatish Taseer was travelling in Sindh, Pakistan, to conduct research for his book, Stranger To History, he met a mujahir (immigrant) from Jodhpur who commented on the tone of his voice. “You Indian men speak so sweetly. And also wear floral-print shirts,’ he said.

ADVERTISEMENT

Taseer waved it off then, but now, as he speaks over the telephone from his New Delhi residence, the author vividly remembers the man’s smirk. Soft-spoken men, it would seem, were not ‘man enough’ to the burly, aggressive mujahir, a notion he says is only too common all across the subcontinent.

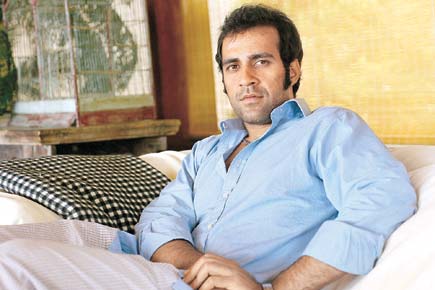

Author Aatish Taseer’s new show explores aspects and conflicts of Indian masculinity

Unequal gender equations and patriarchal notions are far from changing in most of the country. However, in some, mostly urban sections of society, the Indian male is under more scrutiny than ever. Greater discussion of sexual violence against urban women, misogynistic politicians suffering from the foot-in-the-mouth syndrome, women reporting sexual violence against godmen and magazine editors alike — are we waking up to the fact that we finally need to discuss Indian masculinity in all its forms, ugly, anxious and earnest?

Taseer thinks so. He is currently hosting the TV show, Gentleman’s Code, a six-part series, which discusses the psyche of the Indian male. “A lot of ugliness has emerged about male attitudes and I wanted to be able to discuss some of that.”

A still from Rahul Roy’s documentary on masculinity, Zinda Bhaag

At the outset, Taseer admits that the show does not really cut across class and, given that it caters to a prime-time television audience, also ends up focussing on luxury, style and aspirations.

What he does hope to do with the show, however, is debate the role and concerns of the Indian male in middle and upper-middle class. Power hierarchies at work, in social settings and even marriages are no longer rigid. “This ushers in a new reality for men — something they are excited about but also confused and scared of, because they don’t necessarily have the vocabulary to cope with what is happening to them. That territory for me is most interesting,” he says.

Till We Meet Again

Taseer says he is curious about how the modern urban experience is playing out around us. “When aggressive ideas of masculinity, which are rampant in India, come in contact with Western ideas of modernity in big towns and cities, men feel threatened and affronted. It translates into violence, too. I think we need to find a way to assimilate these ideas so the transition is less confusing and not violent.”

Taseer says his own ideas of masculinity, fortunately, were first shaped by his single mother. “I grew up around liberal women, so gender equality was a kind of social inheritance. But that was not the case for everyone around me, and a new equlibrium between men and women could cause a lot of upheaval in people’s lives.”

Filmmaker Rahul Roy, one of the directors at the Let’s Talk Men 2.0

The show discusses changing expectations of the sexes, their sexual anxieties, and women’s experiences when it comes to dealing with the men in their lives. The first episode, for instance, discussed the relationship of a man with his mother through the story of filmmaker Karan Johar, who told his mother that marriage was not for him. “That segment threw up interesting ideas and explored the deep, yet difficult bond one man shares with his mother. But what interested me the most in that episode was my interview with Priyanka Chopra. Unlike many women who would want their men to loosen up when it comes to jealousy and possessiveness, Priyanka said she likes her man to be possessive. But, equally, she would like to be free to do what she wants. That, I thought, was an interesting contradiction as well as perhaps an example of why men often complain that they don’t fully understand how women expect of them.” Another interview, he adds, was equally revealing. “I was speaking to singer Anoushka Shankar, who said she was appalled when she realised that she had been invited to a party as eye-candy. She added that Indian men do not make her feel three-dimensional at all, and that she could have never married an Indian guy. That, I feel, says quite a lot about our attitude,” says Taseer.

The female gaze, he adds, is not monolithic “I think women should engage with masculinity and interrogate their expectations just as men should. A lot of gender dialogue fails to acknowledge the complicity of women in enforcing certain gender attitudes, and I feel if we are to really understand urban masculinity, we must recognise the role of women in shaping it.”

Taseer has some interesting observations of what shaped his masculinity and how being born in London, education in the US and living in India and Pakistan, sharply contrasts the multiple ‘masculinities’ he has experienced over time.

“My exposure to the West changed my idea of masculinity. It became important for me to cultivate an interior life, to have a broad range of emotional and cultural experiences that I could share with men and women alike. These are broad generalisations, but I feel men in India and Pakistan can often lack that emotional/cultural life, which only comes really from exposure to the humanities. Men here can tend to be a little one-dimensional — the finance guy never moving past finance, the intellectual confined to intellectual things. They are not perhaps as rounded as they should be.”

Men in India, according to Taseer, can often lack the vocabulary to express their emotional life. “For me, literature opened up new ways of feeling. And I realised that it did not come at the price of being less of a man. I meet many men in India who tell me proudly that they don’t read fiction, they think it’s for women, I suppose, and stick to management or self-help books. Well, only a fool would think that the great novels have nothing to teach him!” laughs Taseer.

Last week, the National Centre of Performing Arts screened films made by four filmmakers from India, Pakistan, Nepal and Sri Lanka. As part of the project, Let’s Talk Men 2.0, the films explored the mind of men in the Indian subcontinent. In 2000, the filmmakers had screened films on similar themes as part of Let’s Talk Men 1.0.

Indian filmmaker Rahul Roy’s film, Till We Meet Again, is a story of four men in their 30s who have troubled relationships with their wives, yet make for caring fathers. The Sri Lankan film in the series looks at a marriage in which the woman finds it difficult to establish a bond with her inexpressive husband. The Nepalese film looks at a gurkha training camp which puts unnatural pressure on men to be tough. In the Pakistani film, four men face the societal pressure to make money.

Roy first began making gender-related films in the 1980s, and they discussed women’s issues. “Somewhere along the lines, I got uncomfortable, not because these films were questioning my own values, but because I was making them without looking at myself.”

The discomfort urged Roy to turn the lens on his own life. “I wondered how does one represent masculinity, which is all-pervasive and ubiquitous, yet something that hides within itself? Dialogue on gender does not speak of men — it largely speaks of women. How, then, do you engender men?” The idea behind the films made under Let’s Talk Men 1.0 was to bring male filmmakers together, who could then — consciously — look at their own gendering process, including ideas of sexuality.

The filmmaking process was revelatory for Roy, who discovered similarities in the way Indian masculinity was shaped across classes. “Almost every Indian man discovers sex and sexuality around other men, not women, and by the time they make the transition to experience, you already have set ideas of women. Almost every male jokes about how marriage is alright for the first three months, and then it is a pain. I find it sad that the fate of the most important decision in your life is pre-decided. Do men have resources to elaborate these thoughts? How do men negotiate these fears? The tug of war between their mothers and wives, I know, makes most men paranoid and they have no idea of how to go about it. So many men I spoke to told me, that in this case, they’d try explaining things to their wives, but after a point, there would be no other way than to hit them into silence.”

Urban masculinity, however, has changed in many ways, too. An area which intrigues Roy about Indian masculinity is the increased possibility of non-sexual friendships between men and women today. He also says that the changing dynamics at workspace are threatening men on many levels, even as they try to negotiate women’s presence. “This struggle is significant, and is happening for the very reason that our institutions are not gender sensitive in the first place. This discrepancy manifests in peculiar ways — like the Tarun Tejpal case, where the supposed fountainhead of feminist ideas is mired in a rape case. The same goes for caste in India.” In his film Roy highlights this confusion through a man who is unsuccessful at work. “When his wife is out earning, and he does domestic chores, he runs himself down calling it ‘faltu kaam’. Because that’s not a ‘man’s place’. It must be a woman’s.’Let’s Talk Men 2.0 concentrates on South-Asian masculinity because Roy feels a common tapestry emerged while trying to find narratives of masculinity.

Men, he feels, feel a greater need to talk about themselves in the aftermath of the Delhi gang rape in December 2012. “To me, this is the largest public expression of masculinity in the longest time. Somewhere, men are trying to reflect on their gender, which is a good thing. The problem with masculinity is that is it everywhere, but is invisible in discussion. It is hardwired, but needs to be reconfigured. Masculine ideas need to be changed and rejected if they are not positive,” he says.

We need more examples of positive masculinity out there. So many Indian men are domestically involved, divide chores and are caring. But where are such role models? Masculine images out there in urban society are boyish, masked as ‘youthful’ — aggressive without responsibility. When you segregate the sexes, and then throw them together at workplace, for instance, it results in passive-aggressive behaviour, which many men mask under the jokes they crack about women. We need to speak about it empathetically and emphatically to understand indian masculinity.

Paromita vohra

Filmmaker, who makes films on gender-related issues

Discussing Indian masculinity makes most men uneasy. Jokes abound, of course, about going to thailand, blowing up money and so on, but, culturally, we are not at a point where we sit down and speak about men. I think, when we speak of indian masculinity, we must speak of how class influences it. Urban, educated men are better off and have the means to work around anxieties. the message of what indian masculinity should be has to percolate to rural india and smaller towns, too. there is no interaction between the sexes. we live in an insanely structured society — on one hand we have these sexualised images in cosmopolitan india, but the guy on the street has barely interacted with women in a sensitive way. That must change.

Anuvab Pal

Stand-up comic and writer

The fact that we are talking about masculinity itself is a significant change, because Indian masculinity is just something that is taken for granted. This means that we see talk about gender issues as a relationship between men and women, not just as women’s issues. Indian masculinity is being challenged because of broader changes at workplace, in property laws and issues around inheritance. These changes have changed the traditional Indian family set-up, where the patriarch had the last word. It is unsettling for men and makes them rather anxious. Most men are alright when women work outside home, but they don’t want to accept the independence which comes with it. They want to be the consumers, but not deal with the sacrifices which come with the choice. The power the indian male enjoyed before is now being challenged — how does he negotiate around the fact that the women in the family may be in live-in relationships, work or have a boyfriend. in short, things he could ‘control’ earlier?

Professor Sanjay Srivastava

Professor, Sociology, Institute of Economic Growth

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!