While last week's Twitter trend #TalkToAMuslim reminds us that discrimination against the minority in this country is far from over, opinions on the trend debate whether or not it's helping us fight reality

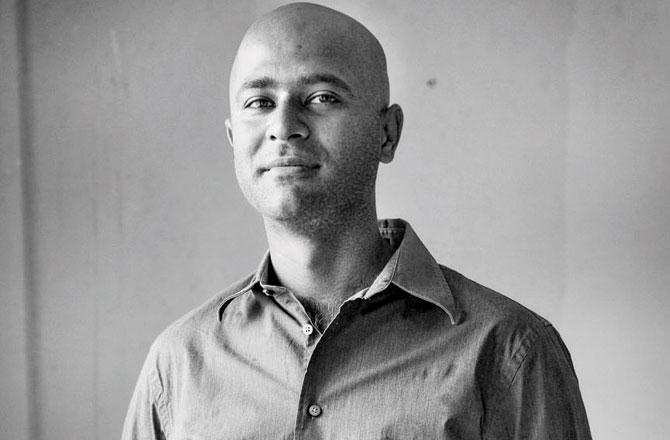

Photographer Mohammad Saiyad says that as a Muslim, he has had a better life than his parents did. Pic/Suresh Karkera

As research head for a hugely popular crime series, Shamael's job involves routinely speaking with the police. Often, while discussing atrocities and criminals, the police make a passing remark, "Muslim hain toh aisa hi [crime] karte hain." Shamael doesn't react, and when she gives them her business card, which has her full name, Shamael Khan, the officials sheepishly apologise, "Sorry, madam."

ADVERTISEMENT

Shamael, 30, laughs as she tells us this. "My name doesn't easily give away the fact that I am Muslim," she explains. There are only a privileged few in India, who can proudly wear the Khan tag. For Shamael, however, her surname proved to be an inconvenience when she moved to this city from New Delhi and hunted for a house. Single and a media professional, she wasn't the ideal tenant. And, she was Muslim. "After I had paid my deposit, the landlord said he wouldn't rent me the flat. For two nights, I roamed the city, until I finally found a place," Shamael recalls. "But, I have faced more discrimination as a woman than as a Muslim."

Zainab Sikander tweeted this photograph in support of the hashtag

This is probably the reason why Shamael will not subscribe to the #TalkToAMuslim movement that Twitter was ablaze with last week. The trending hashtag was a response to the political mudslinging by the BJP at the Congress, and media reports about Congress president Rahul Gandhi attempting to garner Muslim votes and rejecting Hindu demands. On July 17, actor Mohammed Zeeshan Ayyub was probably the first to use the hashtag, when he tweeted in response to a news headline: "I am a Muslim. I also happen to be human like you. You can talk to me." The hashtag polarised opinions — those who adopted the slogan quickly in an attempt to talk about prejudice against Muslims, and those who dismissed it as patronising and uni-dimensional. Both camps included Muslims and non-Muslims.

The Other among Us

"No one should be made to ask to be accepted," says Shamael. Nazia Erum, one of the strongest voices to emerge out of the Twitter discussion, says that #TalkToAMuslim riled up people because it "states things as they are". Erum is the Delhi-based author of bestselling book, Mothering A Muslim, for which she spoke to children and parents across 12 cities to find out what it means to be a middle-class Muslim kid in India. Commenting on the hashtag, Erum says, "People think that they chat with a friend (who they don't consider to be 'that' type of Muslim) without having any of the hard conversations. Or an interaction with the neighbourhood Muslim tailor or meat supplier, and that's enough.

Peace educator Chintan Girish Modi says we need to confront our biases

But, you need to talk to Muslims and ask them how they feel marginalised." Let's not pretend that there is no pigeon holing of Muslims for political gains, she says. "It is so commonplace to see us stereotyped in primetime news. A whole community made to feel like they are untouchable. What the hashtag forces people to do is to come face-to-face with this reality," says Erum. Former advertising professional and now a life coach, Andheri resident Farzana Suri, 45, will attest to this. Suri says that currently, she is the only Muslim living in her block and that, too, after she was interviewed. "I suppose they were checking to see if I was a 'typical' Muslim. Someone said, 'Google her and you will find out more'," she tells us.

A Muslim is not a Muslim

A Kandivli Thakur Village resident, 40-year-old photographer Mohammad Aslam N Saiyad has had an issue with noise pollution in his area, but he dare not complain. "People's first reaction will be — How dare a Muslim complain? But noise pollution is a nuisance for everyone, right?" he says. Saiyad says that he has largely had a better life than his parents did. If there is discrimination, it has come in the manner of Internet trolls, whom he religiously blocks on social media. What he wishes people would get is, "Muslims are not Muslims." Puzzling, right? He explains, "The way it is here in India is that Muslims are Muslims and non-Muslims are Marathi, Gujarati and so on. Muslims are Marathi, Muslims are Bengali, too."

Life coach Farzana Suri, says people often wonder why she doesn't look like a "typical" Muslim. Pic/Satej Shinde

Among all the markers of your identity, it may seem that the Muslim has to deal with his or her religious bearings the most. It is forced upon the community, from forces both internal and external. There is no running away from that identity marker. What's more, Indian Muslims have learned to adapt to prejudice, as they will tell you. So, a Bangladeshi domestic help will pretend to hail from Nepal just so that she can get employment in Mumbai. So, a Muslim ward adhyaksh for the Congress, who had worked for several years for the Borivali East ward, wouldn't even dream of standing for the BMC elections. It is a given.

Zainab Sikander, 32, a New Delhi-based writer, was also among those who vociferously spoke in support of #TalkToAMuslim. She tweeted a photo of herself holding a placard in response to Gandhi's tweet and the context of the allegations that the BJP was making against the Congress. She feels people have made this hashtag to be pro-Congress and anti-BJP, which is not at all the case. "It could have been any politician — Mamata Banerjee or Chandrababu Naidu, even — or any party at all, who made Muslims seem like aliens," she says.

Omair Ahmad

Sikander goes on to point out that under the Sampark for Samarthan (Contact for Support) campaign, the BJP has met Bollywood celebs like Salim Khan, and religious heads like Jama Masjid's Shahi Imam, and business bigwigs such as Sirajuddin Qureshi. "It seems that it is okay when the BJP talks to Muslims, but not when the Congress does," she says. More than addressing discrimination, Sikander echoes Erum's words and says that "humanising needs to happen". "Indian Muslims are from this country and it feels like I still have to justify this every time my patriotism is questioned," she says.

Shifting the onus

#TalktoaMuslim follows other dialogue initiatives, such as Karwan-e-Mohabbat or Visit My Mosque Day. Saiyad, for instance, has held photo walks during Ramzan at Mohammed Ali Road in an attempt to not just encourage street photography, but also get people to get up close and personal. Erum, after her book's success, has been approached by several parents, both Muslim and non-Muslim, to start support groups to address Islamophobia in their children's lives.

Nazia Erum

Omair Ahmad, however, is not convinced that #TalktoaMuslim is the way forward. A New Delhi-based writer, Ahmad defends his stand by saying, "We all incorporate multiple identities. Why would you need to single out one particular identity and talk to somebody because of that? It is slightly bizarre that I would address my friend as Dalit or Jew. Why reduce people to this flat identity? It's demeaning."

A better hashtag, then, suggests Ahmad is #ListenToAllCitizens. That way, the onus shifts from Muslims having to seek acceptance to the state providing better governance. It is that failure that needs to be highlighted. "You don't have to like or love Muslims. You just have to create a fairer system for these citizens, who happen to be Muslim," he says, recalling the 2015 Dadri mob lynching.

Chintan Girish Modi, a Mumbai-based peace educator who works with students and teachers on addressing Islamophobia, gender-based violence and caste prejudice, says that he is reluctant to welcome or dismiss #TalkToAMuslim. "Some Muslims are finding it empowering because it gives them an opportunity to talk about how it feels to be a minority in India. Others are absolutely aghast," he says.

However, talking to a Muslim is not a substitute for investigating one's own bigotry that comes from family conditioning, formal education or media propaganda. "What we need to do is educate ourselves, and be prepared to confront our own biases. Not every Muslim prays five times a day, reads Faiz Ahmed Faiz, dreams of going to Haj every waking moment. Talking to people with life experiences different from one's own is helpful because it expands one's understanding of life. However, it doesn't make sense to go around looking for a Muslim to talk to, the way one would probably experiment with an unfamiliar cuisine," he says.

If then, you had to listen to Suri's story, she will tell you that her most positive experience as a Muslim was the 1992 communal riots. She recalls how her family of eight lived in the ground floor of their building in Colaba. A wall was completely broken down for repairs, and the only thing that separated that room from the world outside was a curtain. "When the riots broke out, our neighbours patrolled the area to make sure no one could get into our flat. Our neighbours were predominantly Sindhi and Punjabi, but that's not how we saw them. We saw them as people who truly cared for us," she says.

Catch up on all the latest Mumbai news, crime news, current affairs, and also a complete guide on Mumbai from food to things to do and events across the city here. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!