A hunt launched by Parsi Gujarati theatre’s most prolific names winds up next fortnight, releasing fresh faces into a performance pool craving talent

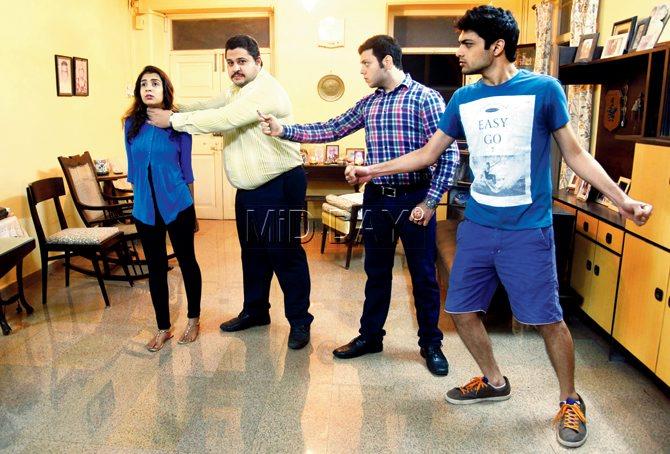

(L-R) The Blazzing Fire group includes Fareez Dubash, director Vistasp Gotla, his mother and producer Pervin, Rashna Karai, Eric Patel and M Pal.

ADVERTISEMENT

A blood-curdling scream echoes through Khan Pavillion at Tardeo’s Zoroastrian Colony. If residents didn’t know better, they’d have rushed to help Rashna Karai.

“Jaraa dheere,” Vistasp Gotla, her director, urges with a half smile, but there’s no stopping the

21-year-old BCom student, engrossed in character.

(L-R) The Blazzing Fire group includes Fareez Dubash, director Vistasp Gotla, his mother and producer Pervin, Rashna Karai, Eric Patel and M Pal. Pic/Bipin Kokate

Members of local theatre group Blazzing Fire, aged 20 to 68, are rehearsing for Chees (scream). Their play has made it to the final round of of Draame Bawaas, a competition launched earlier this year to tap new stage talent from the Zoroastrian community of Mumbai and Pune. Fourteen groups faced eliminations on December 10, and the final five have made it to the finals scheduled for January 13. The winners will get a chance to take part in Laughter In The House Part 2 and be mentored by theatre veterans.

It was an idea mooted by veteran Gujarati actor-director Burjor Patel his actor daughter Shernaz Patel, writer Meher Marfatia, veteran stage director Sam Kerawalla and actor Kim Vimadalal.

Pasheen Kasad, Vistasp Sanjana, Meiron Damania and Xerxes Bharda perform a scene from Three Musketeers. Pic/Atul Kamble

“We judged the teams on their stage presence, dialogue delivery and coordination with background music. Usually, newcomers have butterflies in their stomach, but we saw some bold, moving performances,” says judge Bomi Dotiwala.

At 22, Gotla is the youngest director-producer of Parsi plays in Mumbai. The oldest member on his team, 68-year-old Eric Patel, says he last acted in a school play. “With my height and body, I’m fit to play a police commissioner. A competition is like a sword on your head. Of course, we want to win,” he says.

A scene from Defenseless Creature

The youngest actor in the group, 20-year-old Fareez Dubash joined barely a month ago. “My dad was down with dengue and I was on my scooter to run an errand when I bumped into Rashna. She said she was off for a rehearsal. I was tempted to join.”

Guiding young guns

Four kilometres away, in Byculla’s Parsi colony of Rustom Baug, Huzan Wadia and Rumy Zarir’s group, BigBang Productions, rehearses two plays that made it to the finals — Three Musketeers and Sorry Wrong Number, both directed by Wadia.

Wadia and Zarir, both theatre actors for 20 years, started launched their group this March. “The idea was to hone talent and bring young Parsis into theatre,” says Wadia.

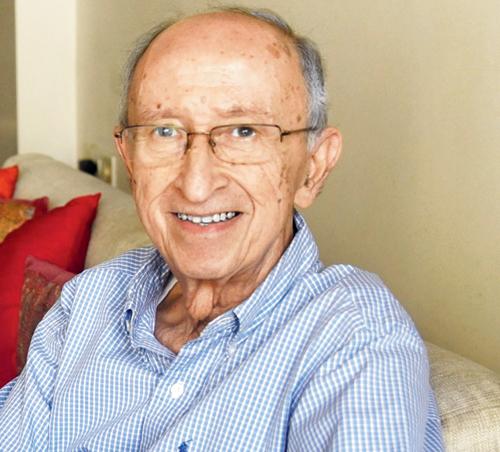

Burjor Patel

Her troupe is a mix of students and professionals, who never tried their hand at acting. For one of them, 42-year-old Dogdau Mehta, this competition is a first stage performance. “I had sent an individual entry for the competition but Huzan absorbed me into her group. I was never really interested in acting as a child, but when I read in a Parsi weekly that the talent hunt was on, I decided to give it a shot. I’d like to take up theatre professionally.”

The lead actors in Three Musketeers are 20-year-olds Pasheen Kasad, Meiron Damania, and Xerxes Bharda, who play the role of a blind, dumb and deaf trio. “Until I joined theatre in 2012, I was not interested in watching plays,” says Kasad, a BMM student, echoing the opinion of most from her generation.

Damania, a law student, agrees. “No one from our generation watches theatre in any language. Our friends only come when we perform. But we are taking it seriously,” says Damania. But Zarir had observed a rise in the number Parsi plays staged round the year. “It is not just slapstick, double meaning humour. Though it’s a long road to revive the golden days, Parsi theatre is not going to die. We have realised that there is a lot of young talent out there, and they are full of ambition. All we need to do is guide them,” says Zarir.

Shernaz Patel

In Pune, Farah Nesargi and Umeed Kothavala are busy fine-tuning scenes on Defenseless Creature, another finalist at Draame Bawaas. “We go by the name Pune Nautankis,” says the 38-year-old product manager with a software company. “The theatre scene in Pune is different. There are no groups; depending on availability, talent comes together for a performance. This doesn’t allow repeat shows. I have been on stage since I was four and continued with the Trinity Speech and Drama course till I got to grade 8, but, opportunities to act are few,” says Nesargi.

The golden days

Parsi plays are now more or less restricted to being staged around festivities like Pateti, Parsi New Year and Khordad Saal, but Burjor Patel fondly remembers the time when every play saw 35 to 50 nights a year.

“Parsi theatre in Mumbai dates back to 1954, and its pioneer, Adi Marzban, directed stellar plays. In fact, he was the pioneer of modern Gujarati theatre too. To be honest, 1954 was a miracle year. Marzban had joined the art and cultural wing of Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Kala Kendra. His first play, Piroja Bhavan was a success and we did 50 nights,” says Patel, who at 24 acted in it.

The period between 1968 and 1978, saw courtroom dramas and thrillers like Hello Inspector apart from the stock comedies. Parsi Gujarati plays appealed not only to Zoroastrians but other Gujarati-speaking communities, including Bohris and Khojas. After acting in plays for Marzban, Patel launched a production house with him in 1980. In 1988, Patel moved to Dubai on work and returned 22 years later, in 2009.

These 20 years coincided with the fall of Parsi theatre in Mumbai, accelerated by Marzban’s death in 1987. “Apart from Pheroz Atia, Dorab Mehta and Homi Tavadia, there were hardly any writers, and Parsi theatre died a natural death,” says Patel.

The same year, nostalgia for the golden days of Parsi theatre was revived when Meher Marfatia began research on Laughter in the House. “Over lunch one afternoon, Shernaz suggested I research and write a book on Parsi theatre of the last century, as some of the actors and technicians were still with us,” says Marfatia who released the book in 2011.

Last year, Sam Kerawala directed the play, Laughter In the House, to pay a tribute to Adi Marzban. The play brought together yesteryear actors including Ruby and Burjor Patel, Dolly and Bomi Dotiwala and Moti Antia.

The play stirred greater nostalgia, and, led to the idea of hosting Draame Bawaas. “We had support from Parsi weekly Jam-e-Jamshed and the National Centre for the Performing Arts, who lent the venue for free. Sam Balsara’s advertising agency designed our campaign,” says Patel, who admits the journey of Parsi theatre’s revival is a long one. “If one really wants Parsi theatre to go a long way, it needs some room in Gujarati theatre. Philanthropists should come forward and support the stage; we need better writers,” Patel signs off.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!