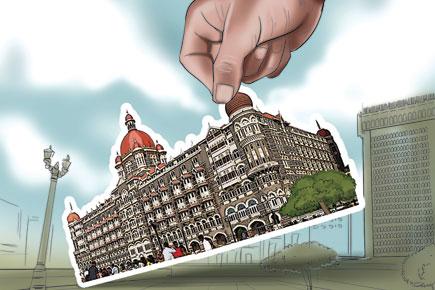

Mumbai's Taj Mahal Palace Hotel has created history by becoming the first structure in the country to get a trademark, but has it 'overreached' by denying artists and photographers hassle-free use of the image of the iconic building

Illustration/Uday Mohite

ADVERTISEMENT

Picture this: It's early one rainy morning. The grey sky is yet to reflect the colour of the sun. You are standing near the Gateway of India, against the regal backdrop of the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, when you have a chance encounter - a spectrum of light flashing across the red-tiled Florentine Gothic dome of the Taj. It's an irresistible vision, begging to be arrested on camera and breathtaking enough for the world to see. You do your part and freeze the moment. The rarity of the image makes it a prize catch. If you aren't someone who takes fancy to social media, distributing the photograph to media houses would have been a fine move to earn a quick buck. But, that would have been the case until a week ago. Now, there's a middleman involved. And, the laborious process might just put you off so bad that you are quite likely to open a new Instagram account, and share the picture there instead.

Earlier this week, the 114-year-old iconic Taj hotel in Colaba became the first building in the country to receive a trademark registration under the Indian Trademarks Act of 1999. That means, the image of the main dome of the Taj Mahal Palace can no longer be commercially reproduced without prior permission from the Indian Hotels Company Ltd (IHCL), which owns the Taj. Any violation can constitute infringement of Taj's intellectual property rights and registered trademarks.

Pic/Getty Images; Imaging/Ravi Jadhav

In layman's terms, the image of the landmark structure cannot be depicted in memorabilia such as postcards, posters, T-shirts etc, or movies, and photographs and artworks on sale, unless permission has been granted. "The hotel is a valuable intellectual property," says Rajendra Misra, senior vice-president, general counsel, Taj Hotels Palaces Resorts Safaris. "We felt strongly about protecting and bringing forth the distinctiveness of this most recognised building in India," says Misra, when explaining the reason behind the unusual move.

But, like all things first, the ambiguity surrounding the 'trademark' is so high that it has already raised concerns among the legal and art community. Though a private property, the Taj hotel is very much part of the collective consciousness of Mumbai, and an irreplaceable emblem of the city's landscape. Hence, as valid as the argument of protecting its intellectual property is, so is the debate around whether cultural landmarks should come under the ambit of such a law. And, if yes, where should one draw the line.

Garima Gupta has incorporated several landmark structures of the city in her artworks

Protecting a brand

While registering of buildings under the trademark law was previously unheard of in India, it is commonplace in the West. Taj has now joined an elite 'trademark' club, which includes the Empire State Building in New York City, the Opera House in Sydney and Eiffel Tower in Paris. "A trademark is a mark that distinguishes the goods or services of one individual from those of others. It mostly includes brand names, shapes, packaging or a combination of colours," says Devika Agarwal, a research fellow at Centre for WTO Studies, Indian Institute of Foreign Trade. "One of the major functions of a trademark is to act as an indicator of the source of the product or service," she adds. That purpose, she argues, is already served under the Indian Copyright Act. "In fact, as per the law, copyright comes into existence the moment you create something. It doesn't even need to be registered. So, Taj already has a copyright for its building," says Devika. The one advantage of having a trademark over a copyright is the 'fair use' provision in the latter, which allows third parties to use the image for research, publication and educational purposes. "Trademark will make it difficult for others to defend fair use," she says.

Garima Gupta

In trademarking the structure, Taj wants to protect the recall value of its structure associated with them and their service, says advocate Dipak Parmar, founder of Cyber IPR. "When somebody uses the image of Taj's structure to promote its services, and that service is not at par with what the hotel is providing, it could lead to erosion of its brand value."

Kiran Desai, partner at Indian Law Partners, points out that an image of the structure has been registered by the Indian Hotels Company Limited under Class 43 of the Trade Marks Act, 1999, which prevents third party use of it, in respect to hospitality services. "So, if you're a restaurant owner or a hotel, and you have used the trademarked image of the Taj to promote your business, then it would make sense for the Taj to impose restrictions."

Arjun Charanjiva

Is Taj overreaching?

The IHCL has categorically stated that henceforth, use of Taj's images for commercial purpose or even for any media purpose would require permission and payment of a licensing fee. "In case anybody wishes to use these images in their work, we are open to discuss granting license, provided such use is commensurate with the reputation and goodwill of the hotel," Misra says.

Desai, however, feels that Taj is "overreaching" by claiming entitlement over images for purposes beyond the industry - in this case hospitality - under which the trade mark has been registered. "Personally, I don't believe they can stop people creating artistic works which contain the Taj. They need to come out and clarify their stance on the issue," he says.

When you think of trademarks, you usually associate it with brands or logos. "While registration of buildings is not expressly prohibited, I doubt that the Indian trademark law anticipated something like this. It would be too soon to comment on how one would work under such a framework," says Agarwal. But, IHCL is confident of having put together a strong case for itself. "It's a pioneering effort in that direction and I am sure it will lead to more initiatives of this nature," says Misra.

In the US, however, the ambiguity around trademark registration of buildings is slowly vanishing. Following several landmark judgments (see box), new ground rules have been laid. One does not need permission to take photographs or use artworks if trademarked buildings are reproduced as part of the larger cityscape, says Washington DC-based lawyer Joshua J Kaufman, who oversees art, copyright & licensing practices at Venable LLP. "If I had to take a photograph at Times Square (in New York), there would be a thousand trademarks in my picture. You think I'd need permission from every hotel, brand or store there - obviously not. As per the US law, if the image is part of a landscape, or is being used by a media publication, you could go ahead," says Kaufman over a telephonic interview.

As part of the trademark policy of Eiffel Tower in Paris, there is restriction on use of images of the structure taken at night-time. PIC/GETTY IMAGES

'Unfeasible and impractical'

Needless to say, the art fraternity is taken aback by Taj's decision with many arguing that this move would only hamper creative freedom. "I think they are being too self-important by trademarking the building," says Krunal Palande, video graphic artist and founder of Nook and Cranny Films, which makes shorts inspired from key landmarks in Mumbai. "They might have inherited the property, but the architecture of this building is a part of the Indo-Saracenic culture. The architects themselves were clearly influenced by the likes of FW Stevens. The building is symbolic to the city and the owners may have complete authority over its physical domain, but do they have ownership on its cultural value? Perhaps that's a question they should ask themselves," he adds.

Sanjay Chaddha, who runs the iconic 100-year-old Indian Art Studio at Kalbadevi, along with his brothers, shares similar sentiments. "Taj is an iconic structure and is synonymous with the city. The hotel should, in fact, be encouraging people to take photographs of the building, so that the world sees more of this place."

Joshua J Kaufman

Garima Gupta, who has incorporated several vestiges and structures of the city in her artworks in the Project Bambai series, hopes that the hotel will eventually come around. "Taj is the most photographed structure in the city and is also a widely used image. I can't imagine being asked to pay money to use it in my work. It's a short-sighted move on their part."

Not everyone, however, feels that way. Arjun Charanjiva, founder of Kulture Shop, which sells premium lifestyle products by leading Indian graphic artists, says, "If it's is a private building with unique architecture and some sort of investment has gone into building it, then I would imagine that any such claim [for trademark rights] could be seen as legitimate. But, Taj is in a unique situation because the structure is treated as an icon of the city or even a monument."

The irony has been aptly reflected by Gupta in one of her Project Bambai drawings, where she incorporates late architect Charles Correa's wise words into the artwork. It reads: "Architecture is a usable art. It is sculpture - but sculpture usable by human beings."

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!