In her new book, researcher Debashree Mukherjee offers a portrait of the film industry from the 1920s to 40s, the studios which helmed it and the satta bazaar that financed it, as it made a transition from silence to sound

Devika Rani Chaudhuri, who set up Bombay Talkies with Himansu Rai in 1934

Can you tell me why there is not a single film studio in the United Provinces, the home of the Hindi language?" The question was posed in the 'Editor's mail' section of filmindia magazine's 1941 issue. The answer to this was a rather, straightforward one: "Because that province has no official gambling dens like the Share Market and the Cotton Exchange, where easy money can be made and invested in films." In colonial India, the only other province where the satta bazaar flourished unchecked, was Bombay. It's no surprise why it became the beating heart of the movie industry in South Asia.

ADVERTISEMENT

Debashree Mukherjee's new book, Bombay Hustle: Making Movies in a Colonial City (Columbia University Press), takes us through the juggernaut, which would eventually propel Indian cinema to dizzying heights. Examining the unpredictable, yet exciting decades where films were making a transition from silent to the talkies, Mukherjee, who is assistant professor at the Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian and African Studies in the Columbia University, offers a rare insight into how film studios functioned and were financed, and how actors and crew negotiated this previously, uncharted territory.

Debashree Mukherjee

The author serves as an insider, and yet not. Mukherjee joined the film industry in the new millennium—she worked as producer, director and even cameraperson—before training her lens on the fledgling years of the movie industry. "Anyone who has ever worked in any capacity in film or TV production will tell you how all-consuming the work can be. And when there is no work you are hustling to land the next gig. Through all the precarities of freelance work, I remained invested in my self-made identity as a media practitioner and I also remained consistently thrilled by the ways in which the city I had made my home and my workplace was so fundamentally marked by cinema. Why did individuals like me continue to throng the city and join the film industry, even though we knew this was a tough place to survive in? Where did these techniques of work and aesthetic idioms come from? Those were the initial questions for me when I started this research," says Mukherjee, in an email interview.

She became invested in the book, sometime after she finished working as assistant director for Vishal Bhardwaj's Omkara (2006). "I switched to working as an archivist at Osian's. I started making trips to the Asiatic Society Library to read newspapers from the 1930s and get a sense of the films that were playing in theatres at the time. From there the project grew into an MPhil thesis, then a PhD, and finally now a book," she shares. Apart from digging into family archives and conducting oral interviews, the project also saw her pore over tomes of film literature, including hundreds of song booklets, publicity artefacts and film magazines like Cinema Sansar, filmindia, and Lighthouse (Bombay), Cinema and Movie Show (Lahore).

/

/

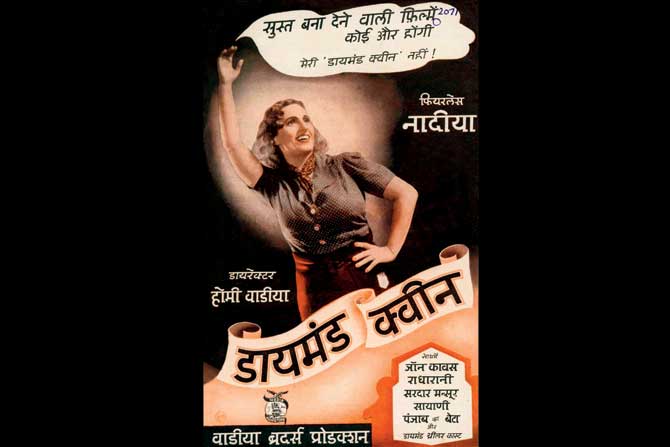

Fearless Nadia announces that her film will energise audiences in this Diamond Queen poster

Bombay's talkie studios, Mukherjee says, only had "superficial similarities with the Hollywood studio system of the same period". And yet comparisons were made, time and again, which the author feels was inaccurate. "First of all, Hollywood's phenomenal commercial and cultural power in the 1930s was because a few players were able to quickly consolidate the whole film business into an oligopolistic vertically-integrated system, where a handful of companies controlled the whole chain of production, distribution, and exhibition. This never happened in India. When companies like the Madan firm in Calcutta tried to do this, there was severe pushback from other film entrepreneurs across the subcontinent. The Bombay cine-ecology of the 1930s shows a wide range of film styles and production models, a diversity of financial practices and shooting techniques, which makes for a fundamentally decentralised terrain of production."

Shanta Apte in an image widely circulated across film magazines between 1939-1942.

She feels it is more useful to compare early film production in Bombay with models that were closer to that in Germany and France, or China and Japan, if at all. "Even in comparison to these other production histories, the thing that makes Indian commercial cinema so unique is that as an industry this might be the only country where local filmmaking efforts were so utterly bereft of institutional finance for so long," she adds.

If anything, cinema relied heavily on speculative finance that came from cotton futures trading. "Cinema and cotton futures became a very attractive pair at this time because cinema was one of the rare indigenous industries that had escaped the economic surveillance of the colonial state. The colonial government was mainly interested in cinema for its possible anti-colonial content and neglected to supervise its financial and industrial activities, even though many producers tried to get the British government to take the industry seriously and support it. This colonial oversight made many forms of local financial trading, which were banned or restricted at the time, look towards film for investment. Cinema itself was a form of speculation and a risky gamble," she adds.

.jpg)

Ranjit Movitone acquired this premises from another film company in 1936, as reported in Ranjit Bulletin, May 9, 1936. Pic courtesy/Debashree Mukherjee

In the book, Mukherjee closely examines the evolution of three city studios—Ranjit Movitone, Sagar Movietone and Bombay Talkies. Ranjit, she says, was founded by two film professionals who already had a wide network of colleagues and contacts they could draw on. "Gohar Mamajiwala was a rising star and Chandulal Shah was making a name as a hit director. Together they managed to rope in other stars such as Sulochana and Madhuri, and also drew finances from their Gujarati credit networks to set up Ranjit Film Company in 1929." Sagar, on the other hand, had a different kind of advantage. It was started as an off-shoot of Ardeshir Irani's famous Imperial Film Company and its founders were from the distribution business. "Bombay Talkies had no direct roots in the Bombay cine-ecology. It was planned by a group of men and women located across Europe and India who actively wooed Bombay's leading businessmen and merchants for start-up capital. What all three had in common in their pre-histories is the fact that they each had one important star whom they could leverage for credit and publicity—Gohar, Master Vithal, and Devika Rani respectively." One of the highlights of the Sagar story, as revisited in the book, is that its "moment of emergence was marked by a famous court case between two studios fighting to retain the services of the actor Master Vithal, popularly called the Douglas Fairbanks of India". Muhammad Ali Jinnah fought the case on behalf of Imperial Film Co. and won.

The switch to talkies came with its own set of challenges, ruffling studios initially, as it meant a huge capital outlay to invest in new equipment and also to hire or train new specialists. "Studios had to be sound-proofed or relocated to quieter parts of town; sound recordists and assistants had to be trained; silent-era stars now had to learn to speak clearly in Hindi-Urdu; dialogue writers, lyricists, music composers and even dialect coaches had to be hired."

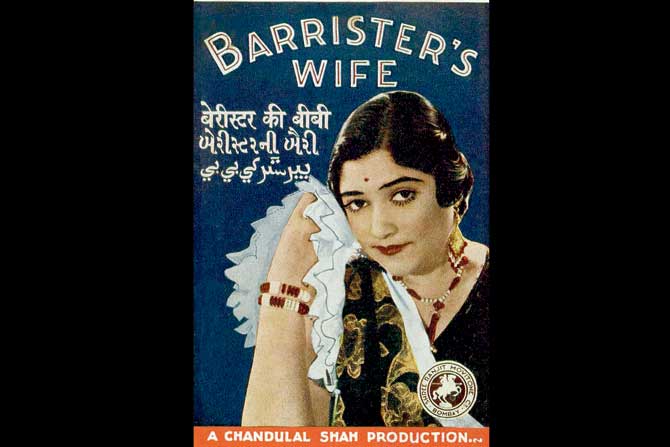

Gohar Mamajiwala in Barrister’s Wife (1935)

One of the silent era stars for whom the transition was seamless, was Sulochana, née Ruby Myers, a Jewish woman who taught herself superb Hindi-Urdu diction, and had early training as a typist and telephone operator before she entered films. "Many others didn't have the right 'mike-suiting' voice or were simply unable to quickly adjust to the new requirements of acting in front of highly directional microphones."

One of the important aspects of Mukherjee's research was understanding the scientific practices embraced by Bombay's filmmakers, be it the way scripts were written—some studios adopted the continuity script, commonly referred as the 'scenario,' which were very detailed—the acoustic technology employed during transition to talkies, and other production techniques like double-unit system, where two films were produced simultaneously in the same studio, sharing crew and equipment, at different points in the day. "Bombay film industry has a deep history of experimentation with corporate work flows and pre-planned production. Why I think this is such a critical history to recuperate is that for too long we have been fed a narrative that deems Indian cinema a peculiar, even backward film form that has been historically unable to modernise. What I hope that readers will get from the book is that these categories of traditional and modern, forward and backward, are false binaries, and actually existing film practices on the ground were more dynamic than we assume."

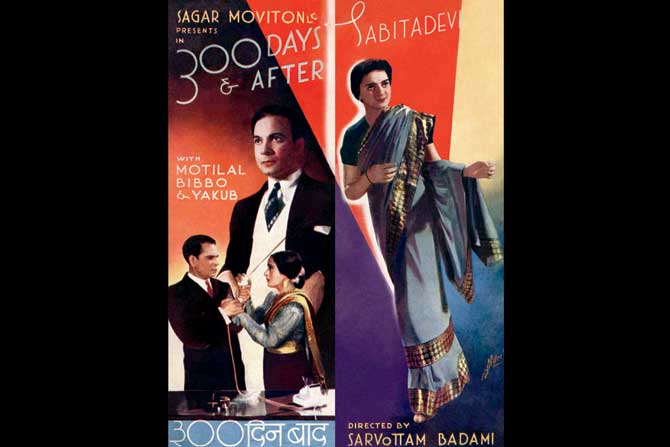

A poster of Sagar Movietone's 300 Days (1938)

Nearly a century on, Bombay's film studios have come to represent an ideal, in the way they functioned as a "family system". This rhetoric also became part of the romantic mythology of that era. Not everything, however, was hunky dory. In the 1930s, actor Shanta Apte went on a hunger strike, critiquing the "extractive practices of the studios". She even questioned her decision to join the movies, in her text, Jaau Mi Cinemaant (Should I join the movies)? "Apte's text is remarkable for its strong critique of the profit-centred, exploitative drive of the film industry. One of the key features of production companies in the 1930s was that everyone was hired as an employee on a fixed monthly salary, including stars. As actresses gradually started to understand that they were the chief asset of studios—that films, film publicity, even film journalism depended on the outsized popular appeal of female stars—they started to demand better salaries. Predictably, studio bosses rarely agreed to their demands and thus, actresses were among the most litigious and litigated-against section of film workers," says Mukherjee. She adds, "The studio-as-family narrative was largely promoted by producers at the time and has been continuously recycled over the years as a way of clearly demarcating the past from the present. It is a nostalgic narrative that creates a rosy picture about the past in order to comfort ourselves that even if things are bad today, there was a glorious time in our film history."Keep scrolling to read more news

Catch up on all the latest Mumbai news, crime news, current affairs, and a complete guide from food to things to do and events across Mumbai. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates.

Mid-Day is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@middayinfomedialtd) and stay updated with the latest news

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!