Senior journalist Rajdeep Sardesai, who examines BJP's sweeping victory in the 2019 elections in a new book, deliberates on the cult of Modi and why the party is not invincible as is evident in Maharashtra

Narendra Modi gestures with then chief minister of Maharashtra Devendra Fadnavis at a public rally in the run-up to the Maharashtra state assembly elections, in Mumbai on October 18, 2019. Pic/Getty Images

The day we speak with journalist-author Rajdeep Sardesai, Devendra Fadnavis is to announce his resignation as chief minister of Maharashtra, just three days after he took oath. The evening ahead is going to be a busy one in the television newsroom he heads in Delhi, but he doesn't know that yet. It doesn't mean, Sardesai, is not prepared. We are discussing his new book, 2019: How Modi Won India (HarperCollins India)—a sequel to The Election That Changed India, which examined the 2014 Lok Sabha elections—but his thoughts continue to be occupied with the ongoing tragicomedy-of-a-power-shuffle in Maharashtra.

"In 2014, the PM said, 'Na khaoonga, na khaane doonga'. But in Maharashtra, his party attempted to tie up with people, who he had accused of corruption," Sardesai says early in the telephonic interview. "Five years ago, there was an uncritical attitude towards [Narendra] Modi. I think finally, questions are being asked and we might be coming out of the grip of the Modi cult. Yes, he is still India's neta no. 1. He is still the dominant figure who towers above all else in our consciousness, much like Amitabh Bachchan did in Bollywood in the late 1970s. However, just like Amitabh's films began to lose their box office appeal, slowly, with time, Mr Modi's appeal may get diluted."

Edited excerpts from the interview.

How much, according to you, has changed for Indian politics, between the last two books that you wrote?

The one thing that hasn't changed is that Prime Minister Narendra Modi continues to be this larger-than-life figure. The big difference then, of course, was that there was a certain novelty factor to him. Now, he has been tried and tested, and is an incumbent. As a result, the BJP and Modi's claims to be a party with a difference no longer exist.

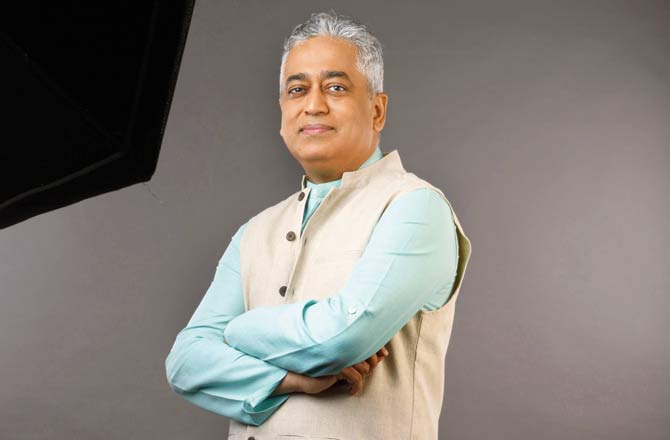

Rajdeep Sardesai

You speak of your apprehension when psephologist Pradeep Gupta (he gave the exit poll numbers for India Today, where Sardesai works) predicted that the NDA would get between 340 and 365 seats. What was your reaction, when they first came to you?

My sense was, 'God, may be for once, the psephologists and I are on the same page'. I, honestly, did think that Mr Modi was doing very well, and that he would cross 300, especially after I visited rural UP, where I heard people talk about Pakistan and Balakot. I soon realised this election was no longer a normal one. Modi had made it very cleverly presidential: it was Modi vs Who? But mine was a hunch, and Pradeep had gone through a more laborious exercise. At the same time, there was this anxiety. When you are an outlier, claiming 340-350, [while everybody else is being much more cautious], the fear is obviously over what happens if you get it wrong; we would have been accused of being the people who got sold out.

You mention the UN report, which stated that 271 million Indians were lifted out of poverty between 2006 and 2016. It's the fastest global reduction and it mostly happened during the UPA's rule. Yet, it's the NDA that managed to ride on the garib kisaan rhetoric. Why?

Things changed for Congress in 2014 with the Anna Hazare agitation. The Congress was perceived by the middle-class as a corrupt party of dynasts, and tired old men. The Congress lost the Indian middle-class after that and it has still not got them back. As far as the garib kisaan went, I think there was a possibility that the Congress could win the farmer over, if it had tried hard enough. But the problem with them is that they want to win elections by default. Even in Maharashtra, its coming to power is not be because of anything it has done. I think the BJP has worked harder at cultivating its votes. And in Mr Modi, they have this strong leader who knows to market his schemes effectively.

The WhatsApp revolution did fuel the nationalist fervour.

WhatsApp has changed the way elections are fought in India. In 2014, WhatsApp was just emerging as a means of messaging. Now, there are more than 400 million WhatsApp connections. Everything is real time. If you have an effective WhatsApp machine, you can create a buzz instantly. The BJP in Bengal alone has 50,000 WhatsApp groups. WhatsApp enables a clever politician and a clever party to really set the agenda, and then again, the agenda doesn't necessarily have to be on genuine information. The WhatsApp communities are powerful weapons; they are like your armed militia, which can go out there, and create a blitzkrieg of information in your favour.

You write about wrestling with your own private and professional demons, having never seen an election where the mainstream media narrative, was so "blatantly one-sided". What went wrong?

I think there has been a deliberate orchestrated effort over the last decade [to polarise the media]. I would say that Mr Modi has been cleverer than his opponents, in controlling the narrative of the media. Today, a large section of the media has become a surrogate of whoever is in power. It's not like these attempts were not made in the past, but in the last 10 years, the attempts have been much more brazen and direct, and the media's capacity to resist has been even less, because our business models have failed. Hence, our dependence on those in power is much greater.

What happens to the objective journalist?

To be honest, I don't know. The objective journalist is now, increasingly finding himself/herself marginalised. The notion of objectivity is that you will question those in power. But today, if you claim the Emperor has no clothes, it is seen as unacceptable. The intimidation of journalists in troubling. We questioned Manmohan [Singh] when he was in power. But with Modi, there is a fear factor.

Narendra Modi or Amit Shah, who, according to you, was the bigger hero, of the 2019 elections?

I don't think the BJP would have won without Modi. They would have still won without Shah. Shah is important to building the BJP's machine. But the machine needs a driver. Without Modi, the BJP would struggle to be the major party. Modi has given them this dominance. Shah is a very good mechanic. He knows the nuts and bolts; he is the fixer. But Modi is the driver, he gives it [the machine] the edge. Shah is the co-driver. What [Devendra] Fadnavis got wrong was that he didn't realise that in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, Maharashtra voted for Modi. He may have also been a beneficiary, but Modi was the real face. So the moment the election became about Fadnavis, the BJP's vote went down by a third. Modi is needed. Take him out of this, and I am not sure that the machine can continue to be invincible.

How would you summarise Rahul Gandhi's contribution to the 2019 elections?

The young are looking for rooted and meritocratic leaders. They want supermen, who can fix the system. Rahul doesn't fit in this sort of universe. He doesn't come to Parliament often enough, doesn't speak strongly. He is seen as someone in politics because he is the son of Rajiv and Sonia [Gandhi]. I think he is too disconnected from the demands of 24x7 politics. He is perceived as far too much of an entitled dynast, and that is in an image that has stuck to him.

The Balakot strike marks an important turning point for the BJP. Had it not happened, you think the results would have been different?

It would have been a closer race, yes. It's like a T20 match, where you are ahead, but you need that one over, where you can just blast off. Balakot gave the elections that momentum. It changed the agenda of the elections. From the real issues of our time, which were jobs, economy, and agrarian distress, it made the elections about 'how patriotic or Indian are you?' As Mr Modi said in one address, 'Humne unko ghar main ghus kar mara'. That kind of rhetoric is difficult to combat.

How significant is the 2019 election in the narrative of post-Independent India?

I think this country has changed in many ways. Whether we like it or not, religious majoritarianism is now beginning to play a greater role in our lives than ever before. The 2019 elections in that sense, set a template for how you can use this form of overt nationalism to try and divide people. On the positive side, there is this hugely upwardly-mobile and aspirational society. Modi is a dream merchant, and a large number of people remain hypnotised by him. In 2014, he promised 'Achhe Din' and in 2019, New India. By 2024, he might spin another dream. But New India is not a garden of Eden. And sooner or later things may catch up [for the BJP], because there has been a difference between promise and delivery. And as is the case in Maharashtra, the machine is already slowly beginning to wear down. The economy and certain decisions the government has taken like Kashmir, and treatment of allies like Sena, is going to begin to haunt the party soon.

Catch up on all the latest Mumbai news, crime news, current affairs, and also a complete guide on Mumbai from food to things to do and events across the city here. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!