Cellphone photography is slowly converting cynical shutterbugs and gallery owners, but how long before it demands the price of art?

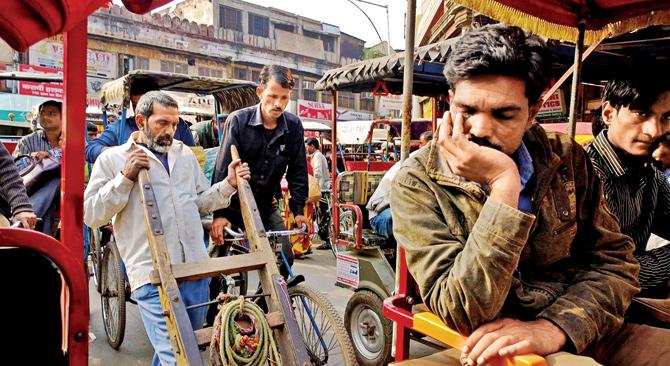

Travellers on the Rajdhani Express, by Chirodeep Chaudhuri, shot on a Nokia Lumia 1020. Chaudhuri hopped onboard the cellphone camera bandwagon a little more than a year ago

ADVERTISEMENT

At the upcoming Delhi Photo Festival (DPF) scheduled for the end this month, a Kolkata-based award-winning photographer’s works will be projected as part of evening screenings. The series, grimly titled, The End, is a culmination of three wintery months that Ronny Sen spent in Jharia, famous for its collieries and infamous for its political landmines.

Travellers on the Rajdhani Express, by Chirodeep Chaudhuri, shot on a Nokia Lumia 1020. Chaudhuri hopped onboard the cellphone camera bandwagon a little more than a year ago

There is a fire, both literal and metaphorical, blazing away in the coalmines, and on its streets and homes overhead. Sen describes The End, shot entirely on an iPhone 5, as “a post-apocalyptic vision where everything has been extracted”.

Ronny Sen shot this photograph, of coalminers’ children waiting for their parents to return at Jharia, on an iPhone 5

Twenty grainy images from the ash-ridden town, in Dhanbad district of Jharkhand, will be shown at DPF; 300 were exhibited at The Gujral Foundation earlier this year.

Old Delhi, India, by Chirodeep Chaudhuri, shot on a Nokia Lumia 1020. Chaudhuri hopped onboard the cellphone camera bandwagon a little more than a year ago

But Sen, 28, doesn’t wish to be slotted as an “iphoneographer”.

A shot of the sea link at Worli by Natasha Hemrajani, taken on an iPhone 5. Ten prints from this series were sold to a gallery at Rs 20,000 each

“There is nothing called cellphone photography. All a photographer needs is an image-capturing device.” It’s a term, he thinks, used mostly by amateurs who share their ‘Mobile Photography Album’ on social media, and by cellphone firms.

While the cellphone camera is the most democratic tool and part of one of the most democratic of the arts, the term cellphone photography is a cause for restlessness. It’s liberating, for anyone can shoot and tweak photos on a mobile. And that is, ironically, also the problem. Cellphone photography is often seen as less ‘serious’, more ‘common’.

Ronny Sen. Pic/Twisha

Can it be good enough to be considered ‘art’?

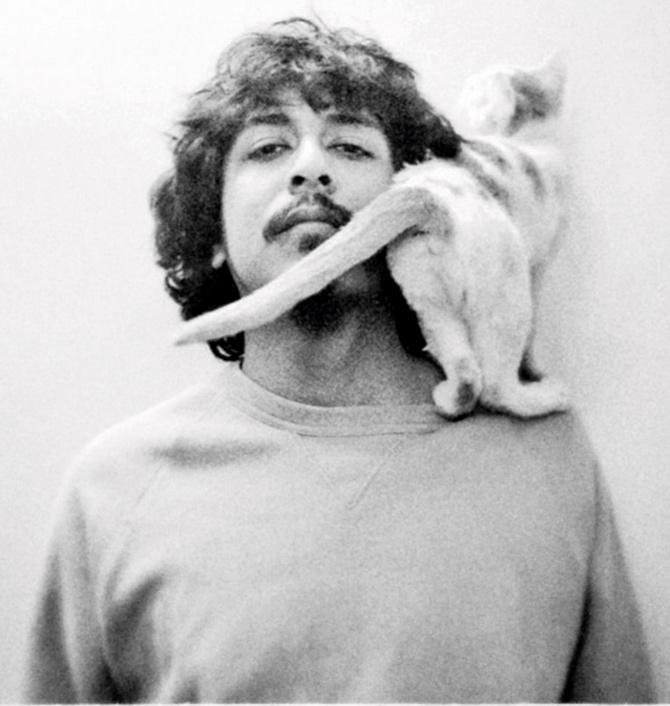

Chirodeep Chaudhuri had stayed away from smartphones and “the whole cellphone photo bandwagon” until students he mentors at various colleges convinced him that it was time he hopped on. For the last year-and-a-half, he has been actively shooting the streets of India and his pet cat on his Nokia Lumia 1020. Practising photography for the last 21 years and calling himself a “compulsive printer”, he also routinely carries out test-prints of his mobile shots. “Cellphone photography has gone from being a tool of rebellion to gaining legitimacy,” he says. But this championing of the gadget — handy and accessible — is new, adds Chaudhuri. “Five years back, the same community of photographers was putting down the cellphone. This complete turn-around is interesting, especially for us photographers who are a notoriously unhappy lot,” he smiles.

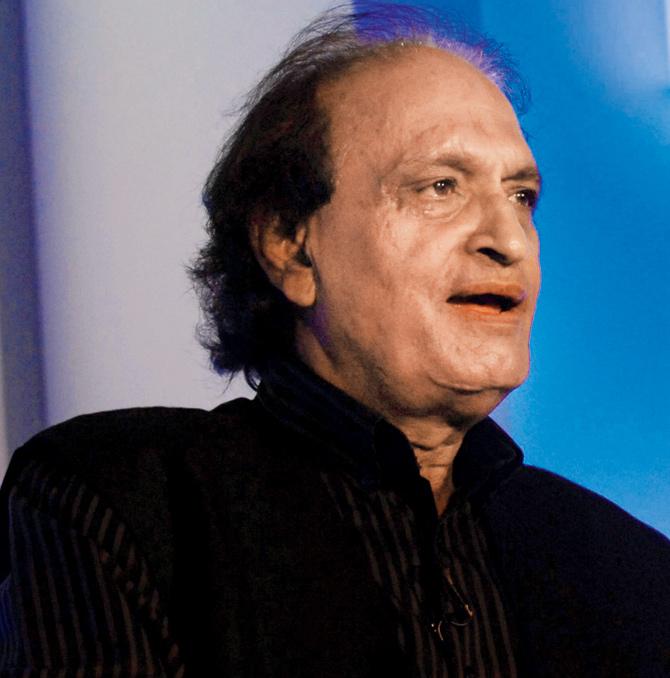

Veteran photographer Raghu Rai has been experimenting with his Gionee Elife E7 but thinks cellphones cannot be the future of photography, unless they come with improvised lenses

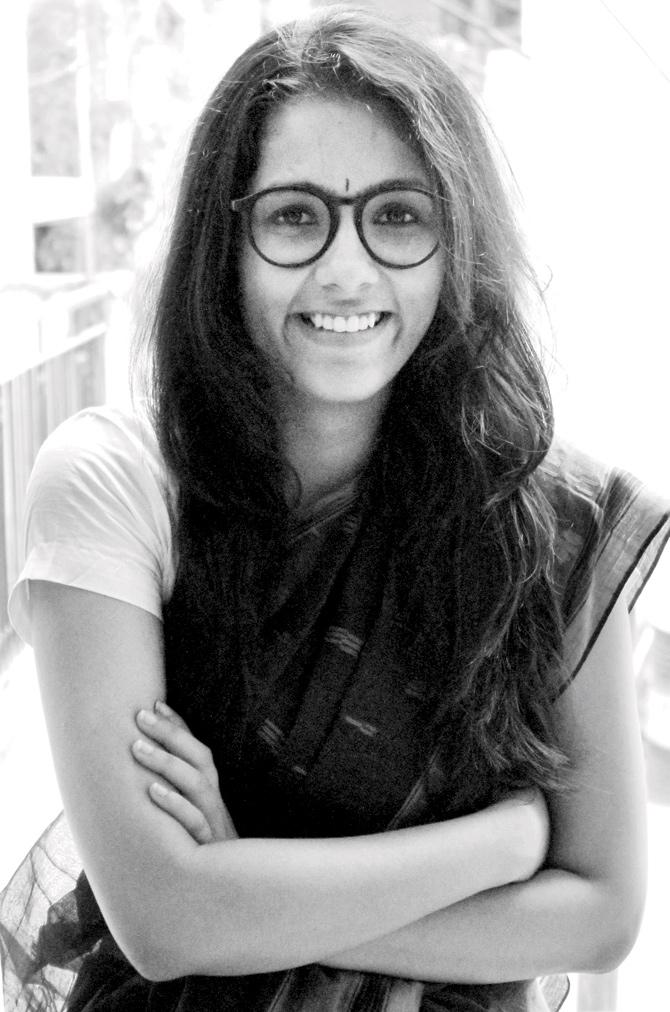

One of the world’s most expensive photo is Rhein II, a manipulated digital photograph made by German visual artist Andreas Gursky in 1999. It sold at a Christie’s auction for 4.3 million dollars. But in the hardly subtle hierarchy of the arts, the cellphone photograph could be suspected of occupying the lowliest rung. Photographers like Sen will argue that cellphone cameras can contribute to a new visual language, just as every other high-end professional camera might. “The anxiety with cellphone photography is similar to the one experienced when digital photography threatened to phase out analog,” says Shilpa Vijaykrishnan, research associate at Bengaluru’s Tasveer Gallery. “The image itself, rather than how it gets made, is more important. The reservations in the art market lie with replication; since you can make n-number of prints, collecting or selling them becomes a problem. You start feeling: Why should I pay for something that I can make on my own?” she argues.

Shilpa Vijaykrishnan

UK auction house Christie’s online sale of photographs, called First Exposure, wrapped up on October 1, with the highest bid for a work by Candida Höfer. The sale saw analogue, digital and mixed media photographic works; Christie’s doesn’t sell mobile phone photographs at its auctions. A spokesperson stated, “Photo-graphs coming up for sale at Christie’s have a traced history and provenance, which is part of their value. Further, to establish an estimate, the condition of the photograph, its edition number and therewith rarity and how the work of art in question has been preserved over the years count enormously.”

Chirodeep Chaudhuri

Does the virile replicating phone-photograph stand any chance then?

Mumbai-based photographer Natasha Hemrajani offers a solution. In 2013, she showcased 12 prints at the DPF as part of her series, Hello Goodbye. The series was a nostalgic look at the city, where Hemrajani grew up, gradually transforming from being Bombay to Mumbai. Shooting fleeting glimpses of the changing landscape from a taxi window and experimenting with multiple exposures, she found her iPhone 5s as a trusted tool. Ten prints were sold to a gallery at Rs 20,000 each. Too much for a phone photograph? “Well, a genre-lised tool shouldn’t matter. Cellphone photography doesn’t need help; it is very much in the art space. And it’s not endlessly repeatable as is often thought.”

The works she sold at DPF 2013 were a limited edition of five prints each. She further hypothesizes that a fifth run of limited edition prints may well sell for Rs 75,000.

Times have changed. The amateurs want the “big” cameras; the masters are experimenting with miniature ones. Veteran photographer Raghu Rai, whose chilling photographs of the Bhopal Gas Tragedy are now historic, shot on a Gionee Elife E7 for 21 days in August this year. Previously slugging a professional camera everywhere he went, he found smartphones to have as accurate a pixel quality as a DSLR. “But cellphones cannot be the future of photography, unless they have improvised lenses. They are, at best, teasers. People shoot on a cellphone and then think, ‘Wow, that’s a good shot. I must try my hands on a professional camera.’”

The greatest misconception surrounding this new wave of digital photography, says Prashant Panjiar, co-founder of DPF, is the misconception that high-end professional cameras are meant for earth-shattering photographs and cellphones for social media. “When photographers want to document how Nepal is rising from its rubble post the earthquake, they use DSLRs. But when they need to meet friends for a drink, they think a mobile will do.”

Hemrajani optimistically says, “The Mumbai art scene is fresh, young and welcoming of digital photography.” But Mumbai is yet to see a cellphone photography show, be it journalistic or fine art. Consider Cellphones in Summer, a 2012 exhibition at [Artspace] at Untitled, in Oklahoma City, USA. It blurred the lines between professional and non-professional image-makers by showing 38 phone-photos, with summer as the theme. Last year, fine art photographer Gerry Coe, exhibited Phone Art in Northern Ireland. He left behind Photoshop to use a range of phone apps to create high-end fine art visuals.

With disappearing dark rooms, Chaudhuri considers a whole generation of photographers who do not know how to shoot on film. A camera does not make a photographer. Rather, the reverse is true, he says.

Christie’s signs off, with, “We do not have a crystal ball to know the future but it is a phenomena to watch, as is street art. The established photographers and icons of photography will always lead the market.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!