Items from the Sir Ratan Tata collection will soon get their own private space at Fort's CSMVS, the museum he built the treasure trove for, to mark his centenary year

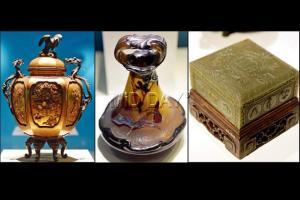

From left: The Shibayama lacquer incense burner, flanked with two dragon handles; a cameo glass flask signed by Emile Galle that dates back to 1885-90 and (above) a green nephrite box from the Qing dynasty. Pics/Bipin Kokate

An inlaid Shibayama lacquer incense burner, flanked with two dragon handles, symbolising the legend of two dragons fighting for the “pearl of wisdom”. The intricate wonder that now sits inside the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalay (CSMVS) has its origins in the Meiji period (1868-1912). It was acquired by Sir Ratan Tata in the late 18th century during his travels to Japan.

The piece is part of an upcoming exhibition at the museum that commemorates his centenary. Titled An Exotic Encounter: Non-Indian Antiquities from Sir Ratan Tata’s Centenary, this exhibition, which opens on September 7, will put on display 90 non-Indian art objects that he acquired during his travels to China, Japan and Europe. From South Asian bronzes, to European oil paintings and Chinese and Japanese sculptures, ceramics and wood works, the exhibition promises a journey into the mind of a man who was not only a great art connoisseur but also someone who donated his entire collection to the erstwhile Prince of Wales Museum in Bombay, to make them accessible to the masses.

In 2012-13, while doing his research for his book East Meets West, Sabyasachi Mukherjee, museum director, CSMVS, immersed himself into reading about the lives of Ratan Tata and his brother Sir Dorab Tata. “While living in London, Ratan Tata continued buying non-Indian and as well as Indian antiquities. Lady Navajbai, his wife was instrumental in realising his wish of transferring his collection from their London residence, York House to this museum, after his demise in 1918. Today, if the country has access to non-Indian art and antiquities, it is largely thanks to Sir Ratan Tata and his wife,” he says.

Between the two brothers Dorab and Ratan, there are about 6,000 antiquities that form the Tata collection. Manisha Nene, co-curator, who has spent 30 years at the museum, knows this collection like the back of her hand. “A major part of it is the far Eastern collection, and even though they have been on display in this museum for years, it’s like a visual storage. That was the idea of early 20th century museum display, where the whole collection is displayed all at once. But, then people don’t get to concentrate on the individual wonders. So, we wanted to create a space where each object is observed carefully, and therefore makes people curious enough to want to know more. What better way to pay homage to a collector like Sir Ratan Tata?” she says.

The pieces for display, therefore, have been carefully selected according to the uniqueness of the material and the story it tells. “We picked five porcelain pieces, about 10 jade ones, six Himalayan pieces, a few European paintings, woodworks and so on. In porcelain also, there are categories. Different varieties will be separately displayed and techniques will be explained. For instance, what is the Japanese cloisonné technique? What are Yokohama prints?” For the curious, cloisonné is the ancient art of carving in metal, where the base is metal and the design is made with a wire, which is later filled with enamel. Yokohama prints are complex Japanese woodworks depicting everyday scenes in Japan, from geishas in various costumes to important train stations and more. These woodworks are part of the reserved collection that will be on display for the first time.

The Chinese jade and porcelain pieces are again among the rarest ones. There is a green nephrite box from the Qing dynasty, the cover bearing the seal of the Qianglong Emperor. From the same dynasty, is a “wish-granting wand”, called Ruyi, made of wood, lacquer and nephrite. Another standout piece is a porcelain octagonal vase with bogu motif made in the Jiangxi province. There are also a few pieces of European glassworks in cameo glasses, some of which are also called “speaking glasses” thanks to the inscription they contain, which carries a message. There’s a glass flask signed by Emile Galle, renowned French glass artist that dates back to 1885-90. The message reads: The invisible is real. Souls have their world.

Sabyasachi Mukherjee

“Those days not many collectors would collect non-Indian antiquities. And even if they did, like the royal Gaikwad family in Baroda, or the Tagore family in Calcutta, it was more for personal ornamentation and also to appease colonial powers. But, Ratan Tata had a plan. He realised that very few Indians would ever travel abroad to see this art. The only way was to purchase them and bring them to India. He had converted his York House home into a mini museum, but his vision was to bring them all to the Prince of Wales Museum,” Mukherjee says.

The man with a vision

Sir Ratan Tata (1871-1918) was an Indian financier and philanthropist, younger son of noted Parsi Merchant Jamshetji Tata, founder of Tata Group. Despite his elite upbringing, he devoted his efforts to various philanthropic movements, and even to the political movements of Gandhiji against apartheid, and Gopal Krishna Gokhale’s Servants of India Society.

A connoisseur of art, he bequeathed a large number of artifacts from his personal collection to Mumbai’s Prince of Wales Museum, now known as CSMVS. He also funded India’s first archaeological excavation at Pataliputra.

Manisha Nene, co-curator

Catch up on all the latest Mumbai news, crime news, current affairs, and also a complete guide on Mumbai from food to things to do and events across the city here. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!