The vast but lesser known collection of late British artist Howard Hodgkin reveals his obsessive love for the beautiful and the unique, and an India that fascinated him

Music writer Anthony Peattie (left) was Howard Hodgkin's partner for 33 years. Pic/Lucinda Burgess, 1984

Music writer Anthony Peattie (left) was Howard Hodgkin's partner for 33 years. Pic/Lucinda Burgess, 1984

ADVERTISEMENT

Last week, Mumbai's art aficionados had the chance to revisit one of Britain's greatest contemporary artists. Sir Howard Hodgkin, who passed away in March this year at the age of 84, was notable for the bold bands and swirls of colour in his abstract paintings, even while he chose to identify himself as a figurative artist. The Turner Prize-winner continues to live on not just through his paintings but also in the form of his extensive personal collection of objets d'art, part of which will be auctioned by Sotheby's on October 24 in London. Select pieces from this auction were shown at a preview in Mumbai on Friday.

The upcoming auction has about 400 works, from European sculpture to Persian tapestries. Hodgkin's personal collection brings together myriad disciplines, including Modern and Post-War British art, Islamic art and contemporary prints. In an email interview, Hodgkin's partner of 33 years, Anthony Peattie, a music writer, tells us that the sale presents a portrait of Hodgkin, through the objects that he chose to surround himself with. "I wanted the sale to be a celebration of Howard, perhaps showing a different side to what is already known of him," Peattie writes in an email to mid-day.

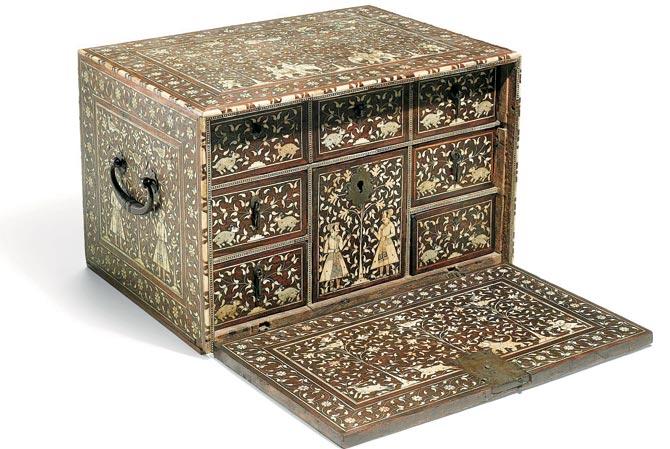

Indo-Portuguese fall-front cabinet

The discreet exterior of Hodgkin's London residence gave visitors no indication of the treasures it held. It is both home and a modern-day grand tour with objects sourced from India to Italy. Yamini Mehta, Sotheby's international head of South Asian Art, recalls how Hodgkin once stated, "I think of collecting as a sort of virus really, and I was infected."

Peattie seconds this, bringing up how collecting ran in Hodgkin's family. His great-grandparents filled their house with English ceramic tiles, for instance. With his collector's instincts, Hodgkin started as a 14-year-old, and loved prints, reliefs, tapestries, and even flags — seemingly disparate objects. "He would refer to his acquisitions as 'costume jewellery for the home': objects with little apparent, practical use, that excited the eye in unexpected ways. He marked auction catalogues with an "MH" when he wanted something. These were his 'must-haves'," writes Peattie.

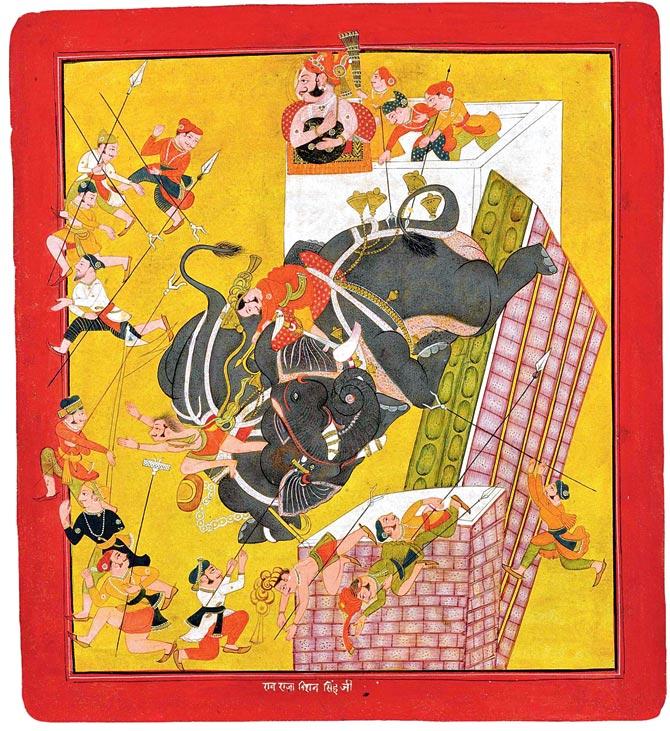

A miniature painting showing Rao Raja Bishan Singh watching an elephant fight, North India, Rajasthan, Bundi, early 19th century. Pic/Sotheby's

Aside from the exceptional, there was also a delight in the orphan, says Peattie, in finding some misrecognised piece, and restoring it to its rightful primary place. Hodgkin once bought an early 19th century mahogany teapot, which stood on four tiny lion's paw feet. Nobody knew what these feet were, until he had them identified as late Roman ivory casket fittings. He later gave them to the British Museum, in memory of his father, Eliot Hodgkin.

Mehta says that it is almost impossible to understand Hodgkin's work without understanding his connection to India. His first visit was in 1964 and he returned every year subsequently, until his final visit to Mumbai just days before his death. One of his finest works is in the form of the giant banyan tree shadow mural that he created for the British Council building by architect Charles Correa in New Delhi.

"India had a profound effect upon his work and his aesthetic sensibility, which fed from the colours, patterns and textures that he experienced there. It is no surprise that Indian works, and Indian motifs are so central to this collection," says Mehta. One extraordinary piece in this collection is a monumental double portrait of Victor Alexander Bruce, 9th Earl of Elgin, and Maharana Sir Fateh Singh of Udaipur. Another is the late contemporary artist, Bhupen Khakar's De-Luxe Tailors, which was given by the artist to Hodgkin as a gift. He also collected decorative art from India and Islamic cultures, and was known for his love of the voluptuous curves of hookah bases and patterns of inlaid metals. "Indian motifs run through this collection, appearing across tiles, textiles, and tapestries. Howard could never resist an elephant," says Peattie.

Hodgkin met Peattie after his marriage to Julia Lane, with whom he had two children, ended in 1975. The decision to auction the collection, says Peattie, is because "Howard liked the idea of a sale after his death." What was once purposeful and inspirational for Hodgkin, now amplifies his absence. "After he died the house was so sad: all these objects remained in place but, after 33 years that we spent together, everything had changed. He wanted to give a lot of money away after his death, and the sale is to raise the funds to enable his executors to fulfil his wishes for others," says Peattie.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!