Child abuse turns children into utilities, to be used and discarded. Child adoption can do the same when it is straddled by delays, paperwork and procedures

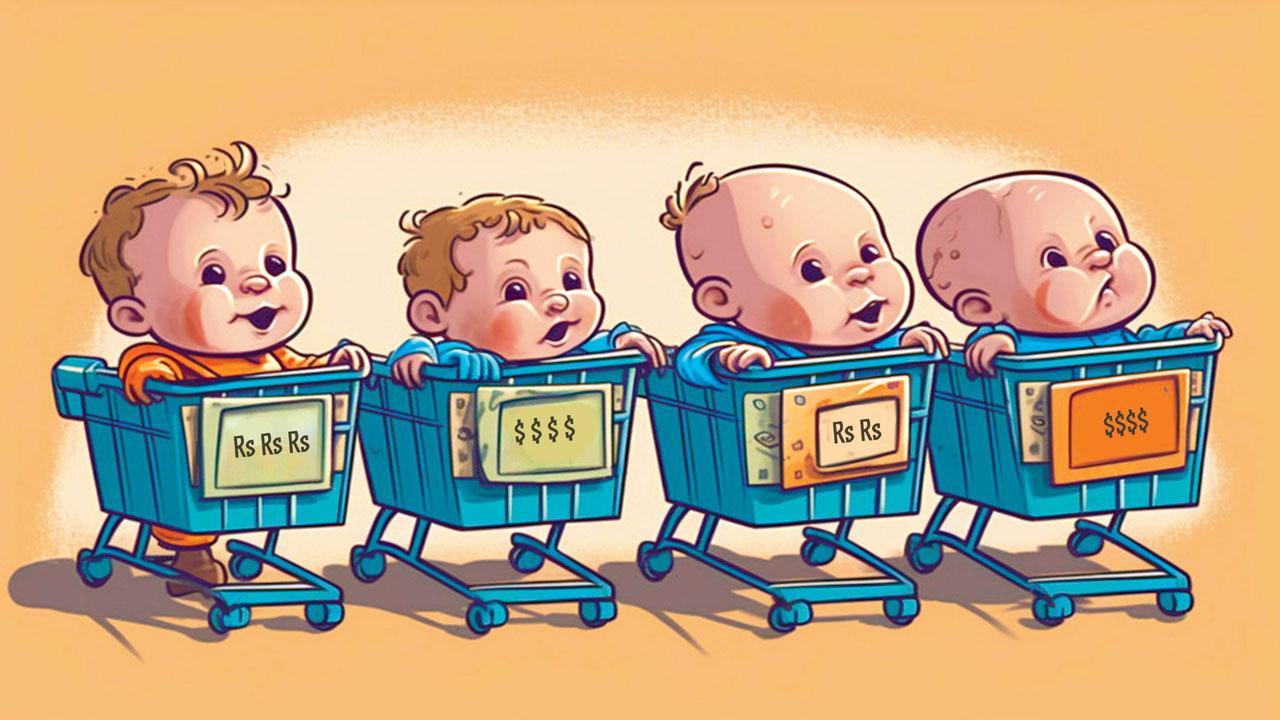

If there was a time when children played with toys, we live in a world today where they are the toys society plays with. In unexpected ways, the adoption process also makes infants commodities. illustration by C Y Gopinath using Midjourney

We all love kids here, right? We think they’re precious, innocent, adorable, kissable and all that—right? We want the best for them—right?

We all love kids here, right? We think they’re precious, innocent, adorable, kissable and all that—right? We want the best for them—right?

Look no further than Gaza to realise how much children matter, not just to Israel but also to America and the other countries who continue scolding Israel while shipping them arms to help them continue the merciless war.

This war has already uprooted over a million children from their homes, separating about 17,000 from their families. The Commissioner-General of the UN Agency for Palestinian Refugees, Philippe Lazzarini, calling it “a war on children”, said that 12,300 children have been killed in the last four months of Gaza. That’s more than the global total of the last four years, 12,193.

So, yes, we do seem to love children a lot.

As though we need more reminding, this week Netflix released Scoop, a dramatised documentary about the millionaire paedophile Jeffrey Epstein and his “nubiles”—his network of hundreds of underage girls and young women just past their teens, all vulnerable and disadvantaged and easily seduced for a few hundred dollars per ‘session’. Epstein made his nubiles available to powerful, rich men such as Prince Andrew, leaving the girls abused, traumatised and emotionally scarred for life.

Here’s the big picture.

Approximately one in seven children have been solicited for sex online.

Approximately one in five girls and one in 13 boys experience sexual abuse at some point in childhood.

About 34 per cent of victims of sexual assault and rape are under age 12.

Around 93 per cent of children who are victims of sexual assault know their assailant.

The majority of child victims are trafficked within their own countries of residence, rather than across borders.

In case you’re feeling smug, this is not a Western perversion: just ask India’s National Crime Records Bureau. One Indian child disappears every eight minutes, often straight from their homes or tricked by child traffickers, to be bought and sold in the market to be sexually exploited, as slaves for free labour or to be forced to beg. And those are only the reported cases.

If there was a time when children played with toys, we live in a world today where children are the toys society plays with. Children are commodities.

Well, you say, isn’t adoption the opposite of abuse? Surely that’s an example of compassionate people choosing a deprived child and making it the object of their love and affection? No argument there—but in unexpected ways, the adoption process makes the infant a commodity just as much as abuse does.

An NDTV report last year put the number of orphans in India at about three crore. Only about 4,000 are available for adoption each year, to about 40,000 prospective adoptive parents. Indian adoptions, both national and international, have been coordinated by the Central Adoption Resource Authority (CARA), an autonomous and statutory body of the Ministry of Women and Child Development, harmonised with the provisions of the 1993 Hague Convention on Inter-country Adoption, which the Government of India ratified in 2003.

Sherry Zutshi, in Bangalore, is one of the women who went to CARA’s website and applied for a baby. In her early 40s, she was eligible for a child up to two years old. She kept her preferences minimal, asking only that it be from Kashmir but later even removing that requirement.

As CARA required, she found a local NGO that would screen her, conduct the home visit and write the evaluation report. She was told the wait could be two years or more.

After four years of nothing, approaching 47 years of age, Sherry decided that she no longer wanted to adopt a child. Then she received a letter showing her the first of the three optional babies handpicked for her by the Ministry, along with some factual details such as the baby’s height, weight and some milestones.

If she rejected this infant, she would be shown another, up to a total of three.

If that isn’t like buying something in a mart, I’m not sure what is. The process sounds unpleasantly like potato shopping at an online store. The child is a record in a database. Based on a photo and numbers on a sheet of paper, it may be rejected like a defective product, and the shopper will be shown a new one.

More important, even in a deeply committed adoption home, a baby is often one of hundreds under the care of a dozen or so hard-working ayahs struggling to give each baby at least a little love along with the bottled milk. It’s a daunting task. In batch-processing mode, it is awfully difficult to deliver the sustained warmth of skin on skin, the cuddles, smiles and eye-to-eye contact that create security and build social skills a baby needs. At the moment of adoption, the adopted child is very often a blank-eyed template for a future human, starved of human touch. Like a trafficked child, it is a statistic, not a person yet.

If she comes alive, it will be because of the stardust of love she found with her new parents.

You can reach C Y Gopinath at cygopi@gmail.com

Send your feedback to mailbag@mid-day.com

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!