Why do three buildings in a Maharashtrian stronghold have sparkling Spanish names? The answer is blowing in the dust

Charmaine Bocarro from La Nina. Pic/Sachin Bawiskar

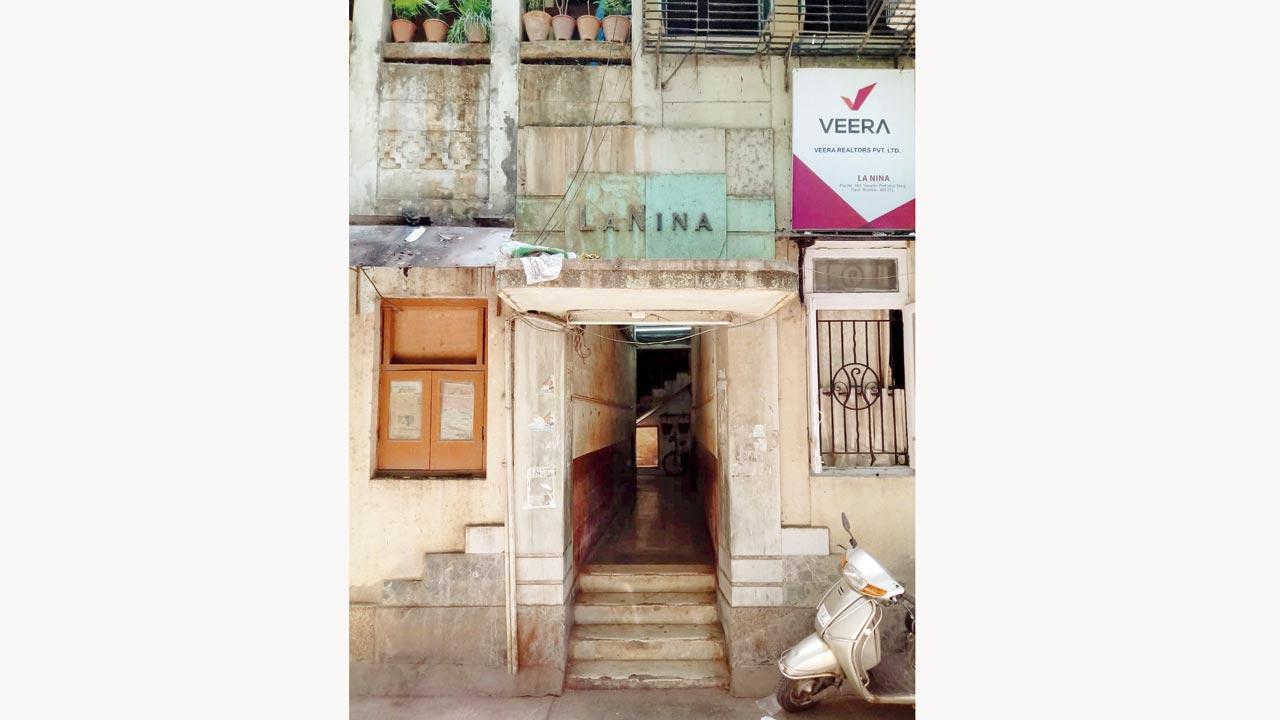

You'll love these,” my friend Gitanjali messaged, forwarding pictures of a trio of four-storey blocks near Bhoiwada police station. On Vasudev Pednekar Marg, in the clamorous core of the essentially Maharashtrian precinct of Parel melding with Dadar East and Naigaon, stand La Nina, La Santa Maria and La Pinta.

You'll love these,” my friend Gitanjali messaged, forwarding pictures of a trio of four-storey blocks near Bhoiwada police station. On Vasudev Pednekar Marg, in the clamorous core of the essentially Maharashtrian precinct of Parel melding with Dadar East and Naigaon, stand La Nina, La Santa Maria and La Pinta.

How Columbus’ historic ships came to christen this cluster of buildings is just one fascinating story waiting to be told in these environs. But a good place to start.

At the gates between La Santa Maria and La Pinta. Pic/Atul Kamble

At the gates between La Santa Maria and La Pinta. Pic/Atul Kamble

Striking in appearance when they rose in 1937-38, amid rows of courts and chawls for mill mazdoors, these three buildings were intended to accommodate St Xavier’s College teachers and other staff. The institution’s Spanish priests were fired by the spirit of discovery inspiring Christopher Columbus to helm four Spanish transatlantic maritime voyages to the Americas.

The seminary in Parel from 1936, till it got shifted to Goregaon, cemented the city’s Jesuit-fostered educational activities. Invoking the saints Anthony of Lisbon and Francis Xavier, its curriculum comprised language studies (English, Latin, Greek), apologetics and history. Philosophy, humanities and theology departments were created from 1938 to 1943.

Deepak Rao with Ganpat Pabalkar at the shop stocking police accessories

Deepak Rao with Ganpat Pabalkar at the shop stocking police accessories

“La Nina, La Santa Maria and La Pinta were once the true pride of Parel. The exterior and interior embellishments and grills on them are of a beautiful kind, designs that masons cannot restore,” says Glenn Roche from La Pinta, whose uncle Dennis Roche taught science and maths, authoring senior school textbooks in the subjects. A closer look at the Burma teak balustrades and banisters reveals delightful details. My favourites are faded wall tiles lining the entrance corridors. Their original contours and colours retained sharpest at La Pinta, these squares illustrate ships on foaming waves, surrounded by seagulls gliding in fleecy clouds.

Also Read: Mina meets Miyake

“The overall upkeep was our responsibility, something my dad faithfully did,” says Vitus D’Souza. Assigned caretaker of these buildings, which were later leased to the police force, his father Cyprian attended to plumbing and electrical issues. “Any complaints and my dad showed up, answering calls at midnight too. He invented a neat system that automatically turned off filled pumps. The waterproof quality of these terraces was fantastic, never a chink of leakage in flats below, in those days at least. Structurally sturdy, the buildings have great internal wiring.” Now demolished, a garage converted behind La Nina into Happy House, served as the D’Souza home.

Carved newel post on a staircase of La Santa Maria. Pic/Sachin Bawiskar

Carved newel post on a staircase of La Santa Maria. Pic/Sachin Bawiskar

Simon Soares was another electrical specialist hired to maintain these properties.

“Except for families like ours, the Roches and Ribeiros, the rest were mainly cops, several earning honours beyond their profession. Professor Ribeiro of St Xavier’s was my father’s friend,” says advocate Charmaine Bocarro. I meet her at the foot of La Nina’s stairway—its newel post top carved with playing card suit images of spade and flower, plus a swastika for luck.Squeezing time from her hectic schedule of court appointments, she directs me to neighbours interesting enough to soon have my head swirl with anecdotes of cops and conquistadors, mill hands and mavericks.

Tile detail of the Columbus ship at the La Pinta entrance. Pic/Atul Kamble

Tile detail of the Columbus ship at the La Pinta entrance. Pic/Atul Kamble

Distributed between the buildings, with the lecturers and lawyers lived Olympians and bikers creating global history. Some with feats celebrated, others unsung. Khashaba Jadhav, a floor above Bocarro, sadly exemplified the latter. At 27, the freestyle wrestler won independent India the first individual Olympic medal, a bronze at the 1952 Summer Games in Helsinki. To think he was initially overlooked for the 1952 squad and bagged rightful inclusion only on petitioning the Maharaja of Patiala, who was a wrestling buff himself.

Joining the police, Jadhav endured shoddy neglect from the authorities, was compelled to fight for his pension and died in a 1984 accident.An adjoining gully, Court Lane (heralded by Nyay Mandir, the Metropolitan Magistrates Court from 1938), was renamed Kashaba Jadhav Marg. More scraps of legacy limp on quietly in his native Kolhapur. On the walls of taleems (wrestling centres) hang sepia-flecked photos of the Pocket Dynamo, as he was dubbed in the glory year, alongside pictures of Hanuman, patron god of the sport. Jadhav’s farmer son lives in their Goleshwar village house, Olympic Niwas.

Vishnu Sakharam Shete, whose father is associated with Surya Mahal and Chandra Mahal. Pic/Atul Kamble

Vishnu Sakharam Shete, whose father is associated with Surya Mahal and Chandra Mahal. Pic/Atul Kamble

A white nameplate embedded on a lower wall of La Santa Maria reads: “Bawiskar CM”. Handpicked with six fellow officers, Chandrakant Bawiskar, who came to La Santa Maria in 1969, rode in a daring motorcycle adventure that hogged the news. One headline raved: “Mumbai to London, 1977. Seven cops. Four Bullets. One hell of a road trip!”

Armed with Carnet documents allowing bike travel overland, Chandrakant Bawiskar, Ashok Aghaw, Sanjay Dani, Subhash Kadam, Bhaskar Dangle, PB Ashtekar and Sanjeev Nadkarni (who rallied on this star team, reprising his own similar routed 1952 journey), with mechanic Francis Pinto, flagged off from Shivaji Park on September 4, 1977. Ranging in age from 24 to 56, they were admonished “Vede zhalaes ka?” by disbelieving families.

Bombay-to-London biker cops flagging off at Shivaji Park in September 1977; at centre is Chandrakant Bawiskar with his wife. Pic/Sachin Bawiskar

Bombay-to-London biker cops flagging off at Shivaji Park in September 1977; at centre is Chandrakant Bawiskar with his wife. Pic/Sachin Bawiskar

Precarious Indo-Pak relations necessitated shipping their equipment to Kabul from where they started. “Where is Vyjayanthimala?” they were asked by star-struck Iranian border men recognising them as being from Bombay. That identity established, a Tehran gurudwara fed the desi boys vegetarian meals. With language barriers, communicating in movement and mime was inevitable. Nervously navigating their Royal Enfield wheels through an earthquake in Turkey, the team suffered unavoidable accidents.

Finally, they reached the cliffs of Dover on October 25. The expedition went on to enjoy sightseeing in Europe, which involved encounters with the Manzano Motorcycle Club on Italy’s autostrada and a nail-biting race against time to fix their bikes in Bulgaria.

“Some of them—my father, Dangle, Dani and Kadam—continue to cut a cake, followed by dinner, every September 4, marking the anniversary of their achievement,” says Bawiskar’s son Sachin in Pune. “Papa’s pillion rider, Ashok Aghaw in La Nina, was his 1965 batchmate and best buddy. We’d picnic and party together. Like us, he hailed from Dhulia. We had the same car model, the Fiat Millecento. With facing kitchens and bedrooms, we chatted khidki mein se. ‘Kya bana hai aaj khaaney mein’ type of talk. Lazarus Das, in charge of training police officers, was also in La Santa Maria. Inspector Saklatwala, among the few Parsi cops, was another neighbour.”

La Santa Maria has the maximum number of retired officers today. La Pinta has a Christian majority, with exceptions like Yogendra Pache, a key figure in stealth exercises of national significance, such as the rescue operation of trapped 26/11 hostages. La Nina has Marwari jewellers with shops around Hindmata Cinema.

“All of us cops’ children are in touch, even those settled in Mulund, Thane and Bhandup,” says Sachin Bawiskar. Non-police families, like Charmaine’s and

Glenn’s, are equally active on our WhatsApp group called Police Officers’ Quarters.”

The curve of compound ringing La Pinta tips the lane to the path towards St Paul’s Church. Across lie Surya Mahal and Chandra Mahal, with arresting Art Deco-meets-Indo Saracenic facades crowned with sultry-sulky sun and calmer moon motifs.

In Ganpati Bhuvan, Naigaon, 90-year-old Vishnu Shete confirms that his father Sakharam was associated with the construction of both. “Bhide, the architect, stayed near Sena Bhavan. The east-open land offered unobstructed views of the rising sun, so the first building was Surya Mahal. They may have thought of Chandra Mahal to balance solar and lunar energies. Like La Nina-La Santa Maria-La Pinta, these are built to last, with solid steel girders.”

Pednekar Marg is packed with signboards announcing services of advocates and notaries. In Ramesh Vedak’s rooms in Surya Mahal, he points to a portrait of Vithal Narayan Vedak: “My grandfather rented this office when the building rose in 1937. Practising at this very spot since 1974, I’m the third advocate generation. My father Chandrashekhar was one as well.”

An Irani cafe which shared Surya Mahal’s ground level with the Vedaks is currently the popular Neesha Bar and Restaurant. Two lanes further east, on Govindji Keni Road, pops up a still standing remnant of Persia, Aspi Irani’s Spenta Bakery—an unusual vegetarian Irani outlet catering to the swell of Gujaratis and Jains in the area. “It was a beer bar I converted in 2006. The maidan was open then, the road clear of vendors,” Irani says. “Making many friends with police people, I have fond memories of them.”

Guiding me through the twisty innards of essentially police turf is police historian Deepak Rao. Walking past the Bhoiwada courts, armed police headquarters and Ganpat Pabalkar’s corner stall hawking police shoes and holster belts. A couple of freshly inducted women cadets check their uniform accessories. Next, we sip elaichi chai in the canteen of the English Police Recreation Hall.

Rao explains the strategic sway this jurisdiction held in central Bombay from the 1920s. “Bhoiwada importantly controlled Bombay’s five battalion camps in Parel, Worli, Tardeo, Marol and Kalina. It has undertaken vital roles in sensitive interrogation, guarding government premises and escorting undertrials to various courts. With thousands of police tenements in these parts, every second person has some cop family connection.”

The cab driver taking me home bristles with opinion. I must be Parsi, he observes in an instant. Am I here because the Dadar colony of my community members isn’t far? When I mention what brings me to Bhoiwada, he exclaims, “Hamara interview lena tha. Pitaji ne ACP ke ghar kai saal kaam kiya.”

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at meher.marfatia@mid-day.com/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!