Navonil Das of the Dev R Nil fashion brand on being a designer who is openly out, using his position to advocate queer-safe spaces and trying to keep the conversation on diversity going beyond Pride month

Navonil Das with his mother Manisha Das Hazra at the Kolkata Rainbow Pride Walk

This is embarrassing,” comes the modest reply when this writer texts designer Navonil Das of the eponymous Dev R Nil brand for an interview request. This is not how interviews with fashion designers usually begin. But then this isn’t the usual discussion about a new collection or trends.

This is embarrassing,” comes the modest reply when this writer texts designer Navonil Das of the eponymous Dev R Nil brand for an interview request. This is not how interviews with fashion designers usually begin. But then this isn’t the usual discussion about a new collection or trends.

ADVERTISEMENT

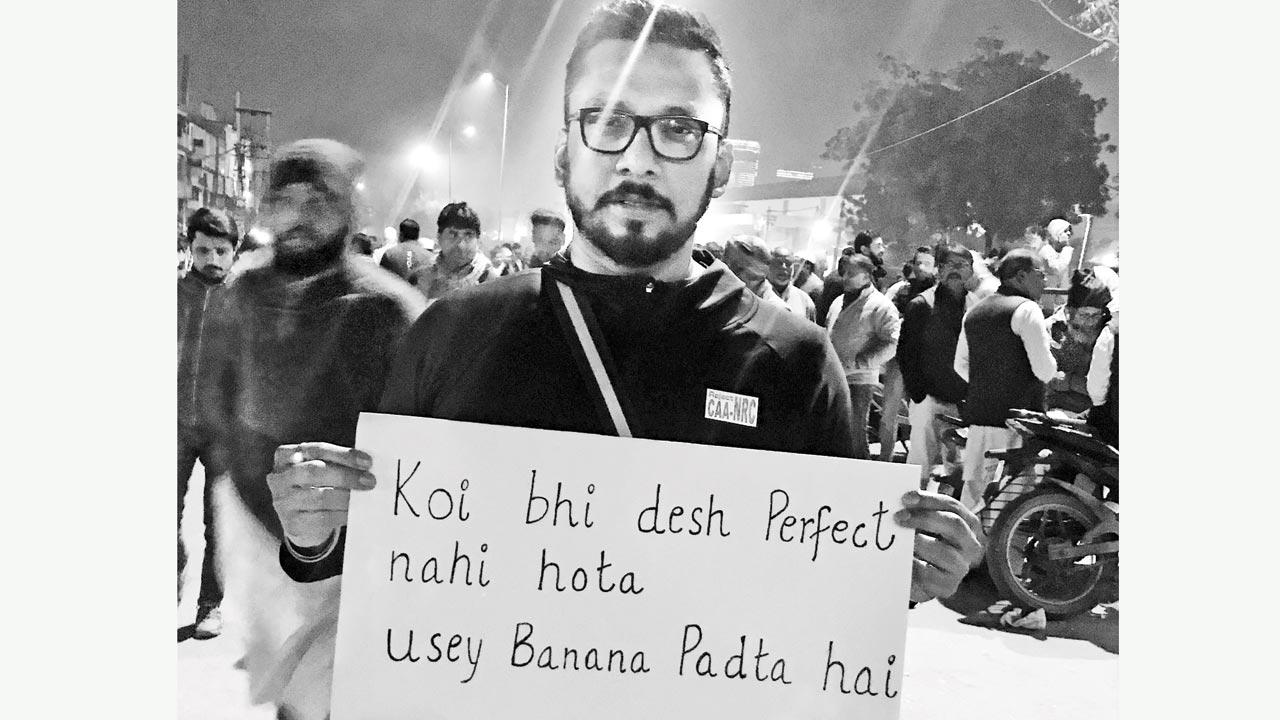

It’s about Das, 44, and his advocacy efforts to build local movements for the visibility of the queer community that goes beyond the activist-influencer matrix. “People who’ve made activism their profession can sport the activist title. I am lucky to have found a place in the fashion industry for 17 years and hope to leverage this privilege to promote the community,” says Das on a video call while waving his right hand dressed in a Pride wristband.

Das came out as gay to his family in 2004, and says it was long before that that he grew aware of his sexual orientation. As a fashion student in Australia in 2000, Das remembers attending the Mardi Gras in Sydney—his first ever Pride event—with his then boyfriend. “When I saw thousands of joyful faces, young and old people of colour, creed and sex, cemented my resolve to come out to my family,” he recounts.

His return to Kolkata coincided with meeting his professional and personal partner Debarghya Bairagi (Dev of Dev R Nil). “Within the next six months, we launched our brand. For the record, Dev and I fell in love before we started our brand,” he laughs. The two are not dating any longer, but they live, work and holiday together. “We have moved on from being boyfriends to becoming each other’s family.”

Navonil Das co-organises the Kolkata Pride which is celebrated each year in December

Navonil Das co-organises the Kolkata Pride which is celebrated each year in December

Since publicly disclosing his sexuality, Das has volunteered with Dialogues-The Kolkata International LGTBQiA+ Film and Video Festival and co-organised the Kolkata Pride. An incident in 2007 when his trans friend was denied entry into a swish Kolkata nightclub pushed Das in the direction of creating safe spaces for LGBTQiA+ people. “The usually friendly manager [of the said nightclub] suddenly turned hostile and said, ‘we don’t allow these kind of people’.” That night, Das founded a group on Facebook called Pink Party to address the unicorn in the room: how nightclubs ignore the grievances of queer guests who in fact, generate steady business for them.

The first Pink Party was launched as a monthly event at Kolkata’s Park Hotel with a group of 50. It is now a marquee fortnightly event with its own ecosystem of 7,000 members and also involves jazz evenings held at various addresses across the country, including Keshav Suri’s Kitty Su nightclubs in Kolkata and New Delhi. “The Pink Party was born out of the desire to create a new sense of space and identity for the queer to allow them to be themselves and with others like them. The funds [generated from the parties] are redirected towards planning yearlong events as part of the Kolkata Pride Organisation.”

The Kolkata Pride, which is also India’s first Pride— started out as The Friendship Walk in 1999. It has run every year since, except during the pandemic, pulling in a bigger crowd every time. “But what is the point of a one-day protest march and after-party?” he wonders.

To give it broader appeal, Das pitched Kolkata Pride as a month-long celebration all through December with notched-up LGBTQiA+-themed activities like Pink Pride Ball, one-act plays, health camps, art exhibitions, a sports day, parents meet-and-greet and a poster-making competition. This carnival-like celebration interlaced by the demand for equal rights is a message of riposte in a fun, sociable way.

Much of the energy that erupts during the Pride month seems to have been hijacked by “rainbow capitalism”, in which fashion and grooming businesses change their narrative and logos to sell rainbow-packaged merch and convey a message of diversity and inclusion of LGBTQiA+ community.

Yet, all this showy representation, packaging the “cool” energy of the queer in beautifully-styled grids, changes little. Especially when confronted with translating opportunity into meaningful action. To wit: the lockdown in 2021. “A large section of transgender people financially support their families by engaging in sex work, and the pandemic affected their ability to respond to a daily income. The situation was worsened by government healthcare disparities.” As part of the Kolkata Fashion Fraternity COVID Relief Fundraiser in 2021, Dev R Nil and Nupur Kanoi donated to the Pratyay Gender Trust—a sexuality trust co-founded in 1998 by Anindya Hajra and other members of Kolkata’s transgender women. Together they adopted 80 transgender families. Das personally delivered groceries and medicines in his car. “My car had an emergency COVID permit, and I covered a distance of 3,000 kms within city limits visiting families in transgender neighbourhoods.”

To engage with the community sincerely and advocate for LGBTQiA+ rights, says Das, there is an onus on fashion brands to put their money where the merch is, donate to queer causes all year round and invest in creating workplaces that are truly inclusive. “What brands don’t understand is that queer people can’t turn their LGBTQiA+ status off when Pride month is over. It takes a 365-day process of enforcing actual change.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!