It seemed awash with good-natured exuberance and everyone seemed to be having a jolly good time.

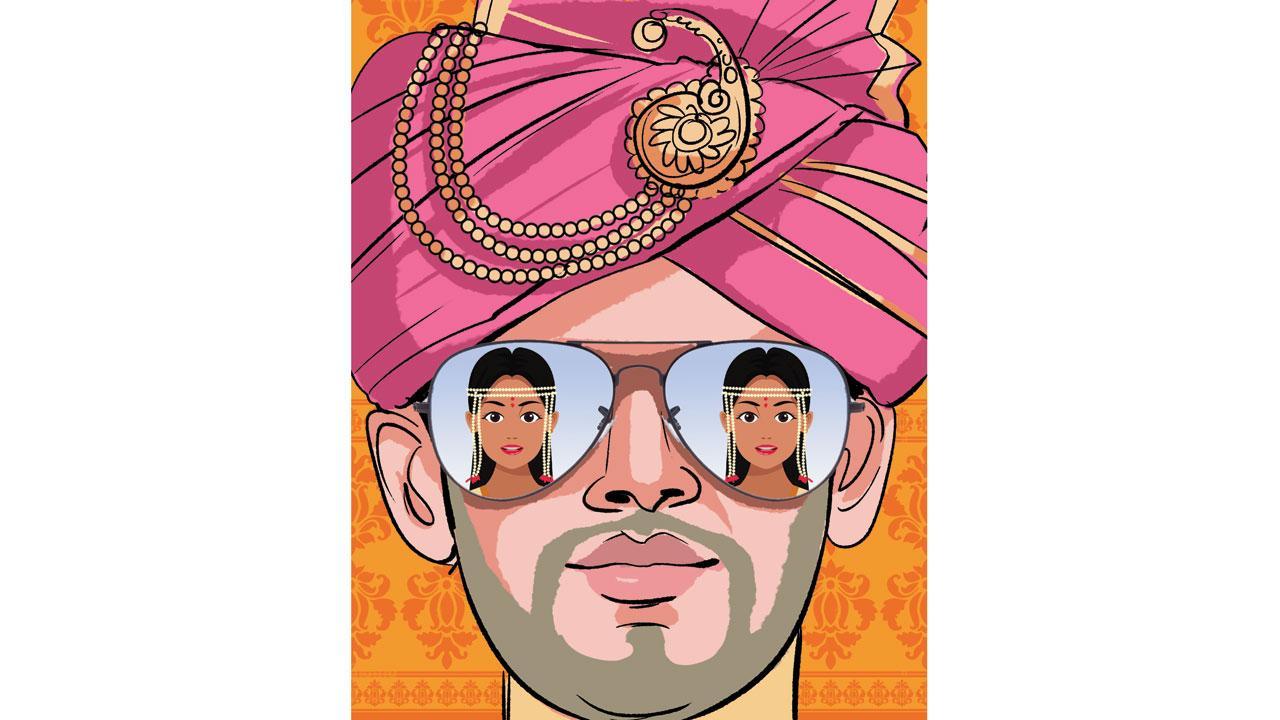

Illustration/Uday Mohite

![]() I don’t know Rinki, Pinki and Atul. Neither do most people who saw their wedding video and had (mostly negative) opinions of it.

I don’t know Rinki, Pinki and Atul. Neither do most people who saw their wedding video and had (mostly negative) opinions of it.

ADVERTISEMENT

Rinki and Pinki, twin sisters and software engineers, reportedly quiet and reticent, from the Mumbai suburb of Kandivli, lost their father a little while ago. Atul, a taxi owner hails from Solapur. They met when the sisters rented a taxi from Atul during their mother’s illness. Over the past six months, it’s said that he was very helpful to the family and one of the twins fell in love with him. The twins do everything together—they even work in the same place. So, they both decided to marry him. Atul, parents and Rinki-Pinki’s mom were all good with it.

Last week the video of their jaimala went viral. It seemed awash with good-natured exuberance and everyone seemed to be having a jolly good time.

Social media filled with the usual “sarvanash” utterances. Men were affronted that any another than they themselves had amorous success. Every news report called the relationship ‘bizarre’. Eventually a complaint was filed by a social worker from Atul’s village. The National Commission for Women, we were told, was also concerned. No one, it seemed, spoke to the wedded parties.

Interestingly the court threw out the case—because it had not been registered by an aggrieved family member. In our society, that could mean a cheated-on spouse, but could as well mean unwilling parents, no matter how old the offspring. When it comes to matters of love and desire, moral propriety and gendered views of women as childlike prey, not idiosyncratic adults, govern the gaze, the conversation and the judgement.

Curiosity and consensuality, almost never.

We all search for love, our entire lives, in some way. And no matter what our relationship status, many feel they have never really been loved.

In truth, attached or detached, we find love many times in our lives. Just that often it appears in unconventional places and shapes. In erotic intimacies experienced within friendship. In relationships that are entirely virtual. In the inexplicable attachment to someone we’ve met just once or twice. The commitment we feel to someone we have long parted from but remember with an abiding flame. The almost painful empathy for a colleague. A romantic love across orientation. The yearning and joy of someone’s social media presence. The simultaneous love for two or three people. That person we barely know but inexplicably keep seeing in our dreams. All kinds of love we rarely recognise as such. Even when we give in to these loves, most of them remain in a shadowy, half-acknowledged place, creating the grounds for much hurt and violence. So, our emotional lives are constantly undercut and soured by judgement of ourselves and others.

Nowadays, English-speaking people struggle against these limitations to intimacy through concepts like polyamory. Terms accord legitimacy to emotions and relationships that have always existed on the edges of respectability. Whether living in terms and categories can ever fulfil the longing for love, remains a question.

Sure, maybe the Rinki-Pinki-Atul story is complicated with a dark seam. Or maybe it’s simple. Maybe this threesome could recognise three times love—romantic, filial, friendly love times three—and choose a relation-shape for their emotions, rather than the other way round.

In the domain of emotion, love can be queen.

Paromita Vohra is an award-winning Mumbai-based filmmaker, writer and curator working with fiction and non-fiction. Reach her at paromita.vohra@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!