Oral histories and relayed family accounts reshape lockdown leanings and learnings for the young

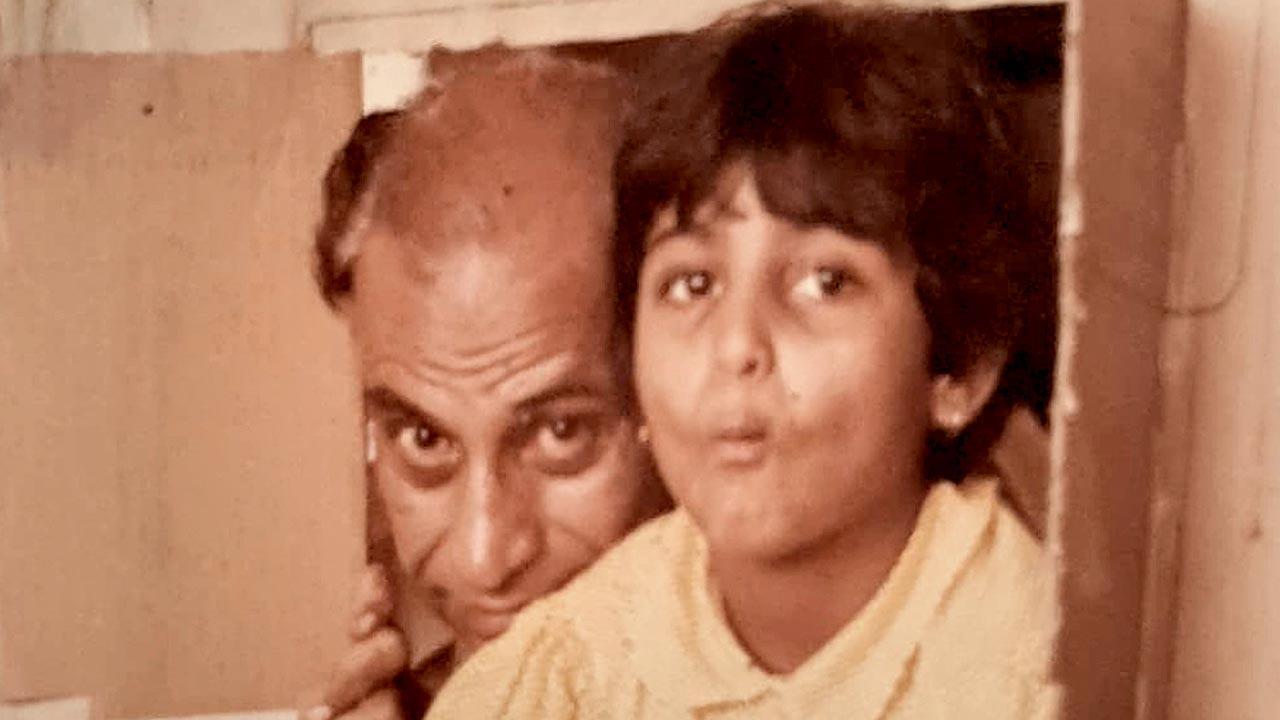

Class X student Gayatri Kapoor’s favourite photo, showing her mother and grandfather in the “house” they made from a refrigerator box

It surprised me and yet it didn’t. My 28-year-old recently bought the second edition of Children Just Like Me, a Dorling Kindersley book he and his toddler sister had enjoyed 20 years back.

ADVERTISEMENT

The two versions portray exciting progressions in real-life snapshots that document 40 kids internationally, with three from India now. Shifting geopolitics, stronger views on environment protection and an easier acceptance of alternate sexualities—like having elder sisters with wives—reflect the infinite complexities of millennial life.

Long lockdown months found Vibhav Mariwala connect his ancestral stories with local history, significantly reorienting his interests and plans

As thrilled with the relatively simpler 1996 book, our toddler daughter had then clamoured for her own pet tales. Having heard the big brother spout the word “anecdote” to mean a story, she lisped, “Tell an anecdote of when you were small.”

We did, again and again. Wearily, skipping not the tiniest detail. Eyes droopy at the end of a long editing day, I tried to hurry the story. “No, wasn’t like that” was the innocent tick-off.

Acupressure therapist Shesdeb Roul with the patchwork quilt Geeta Khandelwal taught him to make for his baby boy in Orissa. Pic courtesy/Geeta Khandelwal

Both keen readers today, their craved family anecdotes have kept us centred in lockdown. Peace isn’t to take for granted with three generations under one roof. Within a bubble, though, the giggles and hugs accompanying spoken stories, fuse focus with fun and calm the senses.

Unpacking the past knits families close in an internal, intangible chronicle of how they view themselves in periods of escalating misery. Social scientists call this the Transition Principle, tweaking the term’s original corporate context of a handover.

These narratives cost nothing but our time and receptivity. They anchor us to engaging pasts, to better navigate the present and be inspired for the future. Oral histories act as assertions, reassurances. Stirring the memory pot, they weave the family into a single entity. Children can feel secure, part of a larger, continuous whole.

“Lockdown is alienating. Pre-pandemic we never realised the need for human contact. Still, it can get suffocating in the same house,” says 16-year-old Gayatri Kapoor, admitting to increased anxiety about school and social events. “I worried for the health of family and friends. Constantly with technology and social media, I felt I’d forget communication in a physical set-up. To the adjustment of online studies instead of attending school was added stress entering Class X.” She attempted video diaries with her best buddy “for a month till we tired talking to a screen”.

Children’s illustrations in the TISS-CRY report on the pandemic include drawing dolphins off Marine Drive. Pics courtesy/Tiss-Cry Study Report

The poetry that Gayatri occasionally jotted became a regular activity from 2020, verse which is currently her coping mechanism and passion. “I’m fascinated by people living in different centuries. My grandparents’ accounts absorb me as if they are novels. A few weeks ago, my parents brought out albums, explaining where and why old pictures were shot. My favourite is of my very young mother, who decided to make a home from the box containing a refrigerator her father bought. He helped build ‘Gopi’s house’, placing a mattress and her books in it. The photo has her peeking out of that cardboard house with my grandfather. In an uncertain world this sort of stability is nice.”

The gifts of unison work. Locate. Listen. Lengthen. Preserve the pieces. Save the scraps. Remembrances from the vintage years are hardly empty nostalgia. Their rich re-imaginings are our rewards.

English Lit professor, Dr PE Dustoor, mentioned in Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy, with this columnist’s mother

“Being in Bombay for a wedding last year, when campus shut down, significantly changed my perspective, and reshaped my hobbies and interests,” says Vibhav Mariwala, studying anthropology at Stanford. Compelled to stay here for 13 months, he returned to college this April. Strolling the city at leisure, particularly in D Ward neighbourhoods he grew up near, he says, “Allowing me my own pace, these walks gradually sparked a deeper appreciation of social history and, by extension, urban policy. My reading preferences went from coverage of large-scale global happenings to local histories. I was lucky to be in the pandemic space with family and friends.”

Extended hours with grandparents—driving his Nani around town, sailing with his Dada—got Vibhav picking up threads of family ties with physical structures abutting Zaveri Bazar and Prarthna Samaj, areas he had scarcely ventured into. “Juxtaposing these stories with my writing and watching the city evolve was transformative. From assuming I’d be in the US after college, I started work for IDFC Institute, a think-and-do tank in Bombay involving policy issues, data governance and public health. Lockdown provided an opportunity to convert my attachment to the city, exploring issues at home, rather than abroad. I’ve written papers on the coastal road’s implications on our ecology, on land-use planning and improving local governance.”

Distances between continents seldom stretch vaster. Zal Joshi, a computer science grad student in New York, was seized by the idea of delving into his ancestry to draw a family tree. “Finding old photos in my basement got me wondering about all the family I’ve not even met before. In December 2019, I wanted to make a trip to India. Shortly after, the pandemic hit. Travel not being an option, put space between me and my roots. It had already been eight years since I visited India. The family tree is a way to reach my heritage at a time when it’s not possible to in person.”

Adopting an intersectional, trauma-informed approach is crucial while recording young voices trapped in this crisis. Meticulously mapping this is a collaborative TISS-CRY research titled, Understanding Children’s Experiences during the COVID 19 Pandemic: Stressors, Resilience, Support and Adaptation. The pan-Indian survey lists silent stressors for nine to 17-year-olds, beyond the obvious loss of loved ones. Alongside top-of-mind issues of death, shortage of medicines and groceries, youngsters fret about financial struggles, trouble accessing online school, lack of outdoor play and peer relationships.

As many as 45.2 per cent report boredom, 41.9 per cent worry. More than one-third (33.8 per cent) of the participants confess to confusion, and over one-fourth fear, restlessness and sadness. Above one-fifth complain of fatigue and anger.

Assessing what contributes to children feeling less disoriented, the paper finds several participants rely on support systems. They mention that speaking to family members (20.4 per cent) and friends (10 per cent) cope with difficult emotions. An 11-year-old-girl from the city has said, “My father tells me stories getting me into a happy state.” A 13-year-old reveals, “I am usually positive, so I try to lift my family’s mood in these difficult times.”

Findings suggest the physical and socio-emotional challenges of adolescence exacerbate the adverse effects for this age group and falling household incomes expose the higher-risk population to physical abuse, mental health concerns and spiralling similar vulnerabilities.

From the confinement of COVID-19 also sprout individual acts of kindness and fellowship, cutting class and age barriers. Master quilter Geeta Khandelwal has shown differences dissolve when connected with a warmly shared skill. Stranded in Bombay, her acupressure therapist Shesdeb (Deb) Roul seemed clearly depressed, separated from his wife delivering their first child in Baleswar, Orissa.

Choosing fabrics from her fabled collection, Geeta taught him to patch together a little godri. Its colours are consciously in the maroon palette and the red-and-white gamcha textile tradition of eastern India, where the boy will grow to cherish their relevance. That it was created in a faraway state by a father, who embroidered the letters of his son’s name, Swayam, in Oriya, marks this heirloom more tenderly. “Hours concentrating on the baby blanket cheered him until it was possible to swaddle Swayam in it,” says Geeta. And Deb responds, “Madam gives old things such new forms. She values rural crafts and mixes their motifs in her designs.”

Deb’s baby godri will drape softer with the years, testament to the power and poignancy of forwarded talents and dreams.

Joint family circles offer uncommon nurturing. Mine moulded much of what I do today.

Author-signed books are among my prized possessions. Star autographs include a cryptic-cool greeting from craggily handsome (at the 2011 Jaipur Lit Fest at least) Tom Stoppard writing in my copy of his farcical first novel, Lord Malquist & Mr Moon - Meher! - Tom!

A personal line from Vikram Seth in A Suitable Boy lights up our bookshelves forever. It refers to my dear Phiroze Uncle, Dr PE Dustoor to academia. He was a celebrated, but unassuming Professor of English at Allahabad and Delhi University. His wife, Dr Homai Dustoor, was founder-principal of Lady Shriram College. Their bond with Harivanshrai and Teji Bachchan forged at Allahabad University over a mutual admiration for WB Yeats, the subject of Bachchan’s doctoral thesis published coinciding with the Yeats centenary.

Page 792 of my 1997 edition of A Suitable Boy alludes to a trio of literary legends, the book’s rare non-fictional characters: “Someone said the other day that they considered me one of those teachers whose lectures students would never forget—a great teacher like Deb or Dustoor or Khaliluddin Ahmed.”

Timidity tinged with pride, I pointed this out on meeting Seth. “That’s wonderful!” he exclaimed, before writing “With all good wishes to Meher and her family” across the margin of that exact page.

I often turn to savour this inscription. I know the inked glow is for keeps. Knowing, too, that it will remain as treasured by the pair of kids who once pestered, “Tell us an anecdote.”

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at meher.marfatia@mid-day.com/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!