What role did Bombay play in the last years of MPT Acharya, one of India’s foremost anti-colonial revolutionaries? In the week of Acharya’s 70th death anniversary, we turn to Ole Birk Laursen’s definitive biography of the premier anarchist-pacifist of the 20th century

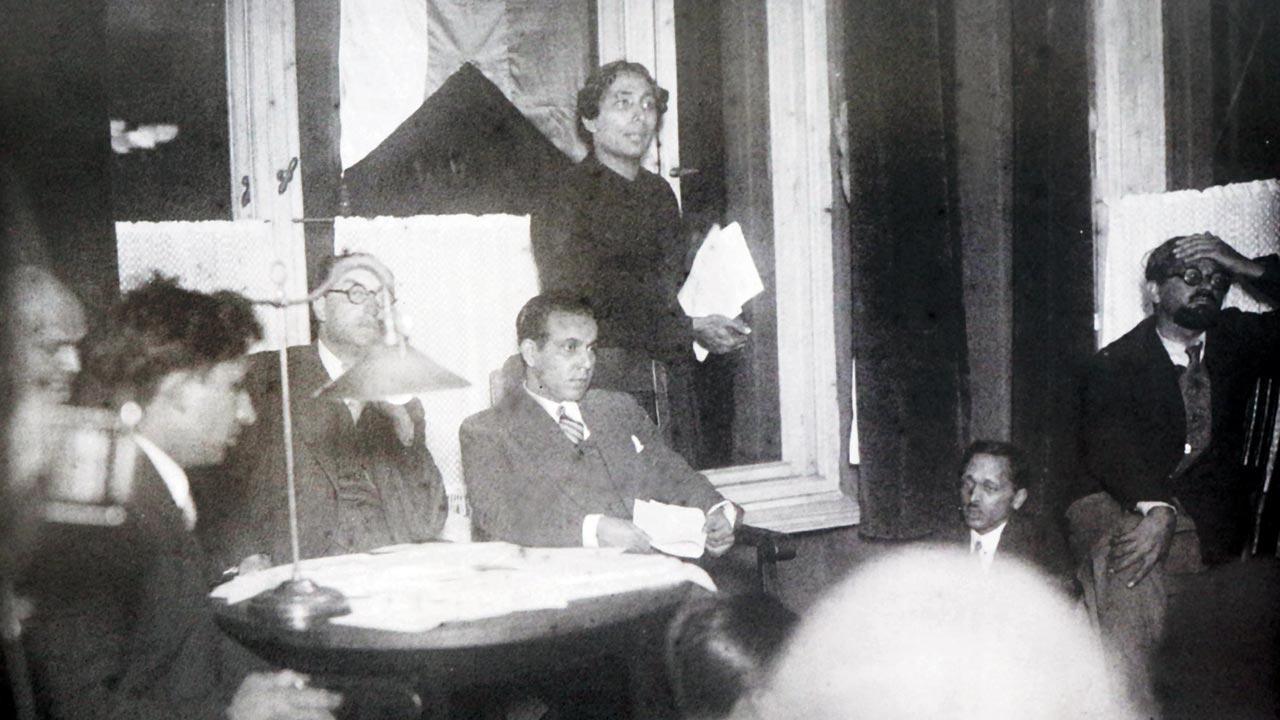

Hindusthan Association of Central Europe, Berlin, protest meeting against Gandhi’s arrest, May 6, 1930. Saumyendranath Tagore is seen speaking, Acharya sitting on the floor

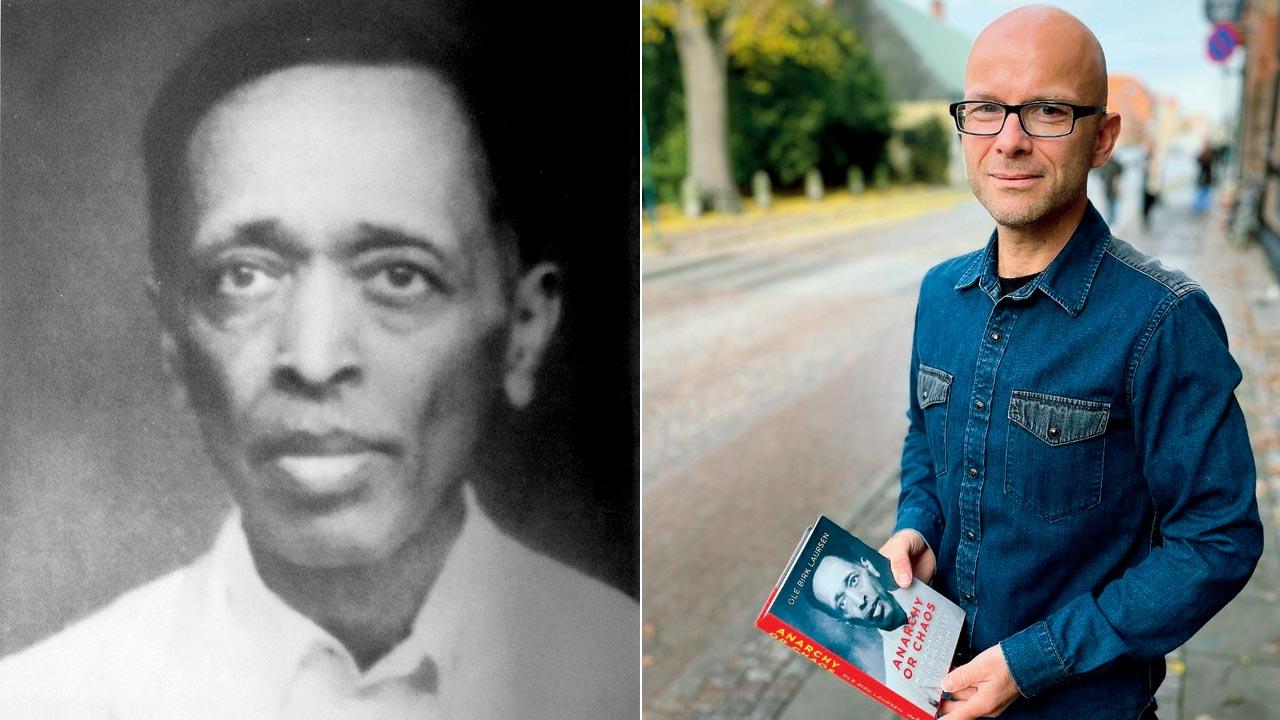

Among the flood of writings on the stalwarts of the Indian independence movement, one book brings this epic era into a sharper, more comprehensive conversation with anarchism than previously assumed by historians. Quoting a staggering range of archival material, private correspondence and other primary sources, Anarchy or Chaos: MPT Acharya and the Indian Struggle for Freedom (Penguin Random House India), offers rare and fresh insights. Written by Ole Birk Laursen, researcher, department of history, Lund University, it amply makes evident that Acharya’s alliance with anarchism charted a pioneering course in the battle for independence.

Among the flood of writings on the stalwarts of the Indian independence movement, one book brings this epic era into a sharper, more comprehensive conversation with anarchism than previously assumed by historians. Quoting a staggering range of archival material, private correspondence and other primary sources, Anarchy or Chaos: MPT Acharya and the Indian Struggle for Freedom (Penguin Random House India), offers rare and fresh insights. Written by Ole Birk Laursen, researcher, department of history, Lund University, it amply makes evident that Acharya’s alliance with anarchism charted a pioneering course in the battle for independence.

Deftly mapping the transition of Acharya (1887-1954), the country’s leading anti-colonial anarchist, this diligently documented, fascinatingly paced biography breaks ground, chronicling in vivid detail the peripatetic journeys of likeminded revolutionaries during a poorly known period of vital Indian history. A good part of that untrodden turf was rooted in Bombay and Sections IV to V of Laursen’s book shine clear light on Acharya’s latter years in this city.

Profiling Acharya’s tumultuous life and leanings—specifically the interesting transitional arc from his militant nationalist to anarchist pacifist stand, his debates with Gandhian thought and unique definition of nirajya (no-government)— Laursen contends that Acharya’s relentless quest for freedom from fascism and authoritarianism charted an extremely different understanding of non-violence and satyagraha. He writes, “For Acharya, the true government of the ‘self’, the individual, had to be decoupled from the nation-state and the idea of constitutional government and instead handed back to the people to attain the meaning of ‘no-government’.”

Acharya’s painter wife, Magda Nachman, outside their 56 Ridge Road home, Bombay, 1937-38. Pic Courtesy/Lina Bernstein & Sophie Seifalian

Acharya’s painter wife, Magda Nachman, outside their 56 Ridge Road home, Bombay, 1937-38. Pic Courtesy/Lina Bernstein & Sophie Seifalian

Laursen’s study strikes out to prompt new avenues of enquiry into the global reach of anarchism in the inter-war years. It challenges conventional accounts of India’s liberation and processes of globalisation, tracking the move towards libertarian socialist rather than Marxist strands.

Describing the book, Priyamvada Gopal, professor of postcolonial studies, University of Cambridge, and author of Insurgent Empire, pronounces it, “A rich, illuminating account of a forgotten but significant presence in the intertwined histories of anti-colonialism, socialism and anarchism. Laursen’s meticulous research and lucid narration redresses a major gap in the annals of anti-colonial resistance and global struggles for peace.”

Born in 1887 in Triplicane, Madras, Acharya edited the nationalist paper, India, in his hometown and Pondicherry in 1907-08 before fleeing the country, and continued writing for publications like Harijan (his main source of income), Thought, Kaiser-e-Hind and Economic Weekly. Following more than an eventful decade of anti-colonial revolutionary activities spread across India, Europe, the Middle East, and the United States—besides three years in Russia—he returned to Berlin in 1922, with Magda Nachman, the Russia-born painter he met in Moscow and married the year before. He became the Berlin correspondent of the Bombay Chronicle. She earned paltry sums from painting.

Ole Birk Laursen with his book. Pic Courtesy/Matilda Skoglow, Sasnet, Lund University, Sweden

Ole Birk Laursen with his book. Pic Courtesy/Matilda Skoglow, Sasnet, Lund University, Sweden

By the mid-1930s, Hitler’s anti-Semitic sinews flexed full power. Half-Jewish Magda and Acharya fled to Switzerland. At their next halt, Paris, they bid an emotional farewell to Acharya’s compatriot, Madam Cama. Then they sailed to the last stop, Bombay, on British passports.

Magda stuck dedicatedly by Acharya, who outlived her, finally succumbing to chronic malnutrition and tuberculosis. She had slogged lifelong to support them both. Incidentally, she and KH Ara happened to be working from neighbouring studios, he at 64 Walkeshwar Road while the Acharyas occupied No. 63 Walkeshwar Road. Magda succumbed to a stroke on February 12, 1951—ironically, just hours ahead of the opening of her last major Bombay show, at theatre director and journalist Charles Petras’ Institute of Foreign Languages, near India Coffee House in Kala Ghoda.

Laursen looks at his work as a starting point that explores the dynamic shifts of isms, questioning past narratives of resistance to dictatorship and oppression. In the Epilogue to the book, he concludes, “As nationalism, fascism and the defence of colonialism rear again across the world, Acharya’s life and extensive body of writings contain lessons for us to learn. As he would have put it, the choice is between anarchy and chaos.”

• • •

Where in Bombay did Acharya reside on returning to the city in May 1935, after almost three decades? He changed addresses a number of times.

Acharya seems to have arrived in Bombay not knowing where to go. About a month after, he wrote to the French anarchist, E Armand, “I am yet not quite free but I am not troubled. I am, however, well received. A consolation.”

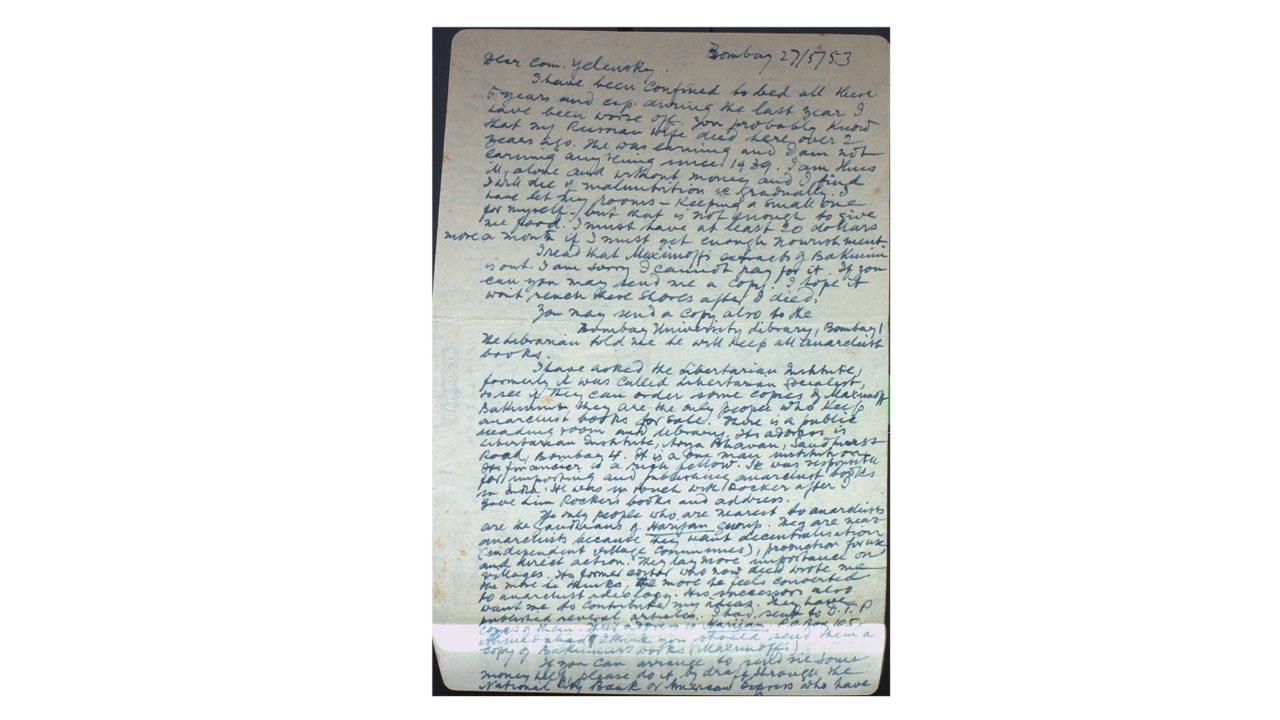

A page from a letter written by a bedridden Acharya from Bombay, to Boris Yelensky, dated May 27, 1953—two months after Magda’s death, in which he confessed to being poor, hungry and diseased

A page from a letter written by a bedridden Acharya from Bombay, to Boris Yelensky, dated May 27, 1953—two months after Magda’s death, in which he confessed to being poor, hungry and diseased

In his letter, he gave his address as: c/o Motion Picture Society of India, 192 Hornby Road, Fort, Bombay. It is uncertain who gave him shelter there, or who he knew at the Motion Picture Society. But when his wife, Magda Nachman, joined him about a year later, they moved to 56 Ridge Road, Malabar Hill, Bombay 6.

Lina [Bernstein, who wrote the book, Magda Nachman: An Artist in Exile] and I have compared notes on their addresses over the years. They were at 56 Ridge Road at least until May 1938. At some point during World War II, they moved to 63-C Walkeshwar Road, eight minutes away.

You say Acharya’s outlook of internationalism was rooted more in the exchange of views than in travel and mobility?

Whereas Acharya’s first 15 exiled years were characterised by mobility and movement across international borders, his time in Berlin and, even more so, in Bombay, were defined by remaining in the same place. However, from Bombay he carried on extensive correspondence with anarchists across the world, exchanging ideas and visions of anarchism and socialism, nationalism and internationalism.

Acharya was equally concerned with India’s freedom and the freedom of humankind. For example, after World War I, he felt it was bad for anarchist movements to be involved in national questions rather than international issues, urging, “Most of the anarchist papers can devote more attention to international questions, especially methods of organising production and distribution in anarchist society.”

Throughout, Acharya appears to express loneliness in India. Was Bombay bleaker for him than elsewhere and if so, why?

It is not necessarily the case that Bombay was more difficult than other places. But having been away from India for almost 27 years, he did not have many contacts to rely on. By contrast, in Berlin he was surrounded by Indian comrades he knew as well as a wide network of anarchists, pacifists and Left-wing socialists with whom he engaged. At the time, Bombay was probably also more of a haven for communists and Acharya found it difficult to get along with them. He struggled to find an outlet for his anarchist writings in Indian papers, causing him to feel more isolated and alone.

Was Acharya and Magda’s interaction with other emigres in the city, like the dancer Hilde Holger, limited because of his views on anarchy and nirajya?

That is hard to assess. On the one hand, the painter Li Gotami and her husband, German-Bolivian painter Anagarika Govinda, had a great deal of interaction with the Acharyas, even having their wedding at the Acharyas’ in 1947. On the other, after Magda’s death in February 1951, Acharya confessed to his friend KS Karanth, “Thanks to her, people are now more friendly to me than before.”

People might not have been particularly friendly to him, probably because of his anarchist views. In a recently uncovered letter from Acharya to the German pacifist Magnus Schwantje, Acharya explained: “There is no intellectual life either among Indians or Europeans. Most of the latter are businessmen who do not care for anything but good living.” The comment suggests he did not get along with many emigres because of his views.

Did Magda’s art practice not widen their circle of supportive friends?

Magda’s art practice certainly widened their network in Bombay. Before he contracted tuberculosis in 1948, Acharya did see other people, including Subhas Chandra Bose and his brother Sarat Chandra Bose. In correspondence, he often mentioned meeting this or that trade union leader, without mentioning names. In my research I found it impossible to trace some of these figures. Nevertheless, from much of his correspondence, and from Lina Bernstein’s biography of Nachman, it seems clear that Magda’s artistic career connected them to friends and supporters in the city.

Your book fills quite a few historical lacunae. How tough has it proved to plug the undocumented gaps in Acharya’s life?

My book expands on CS Subramanyam’s biography of Acharya (1995), which did not cover much of his life in Berlin and Bombay and failed to engage with Acharya’s anarchist or anti-militarist activities from the 1920s onwards. It is this aspect, of Acharya as India’s most important intellectual anarchist, that my book really brings new insights into.

To explore these aspects, I relied on the recent digitisation of many periodicals and archives, and the ability to read several languages to cover many gaps. I have also relied on archivists and scholars from all over the world for help. That said, there were other things I simply could not locate enough information about and had to leave out. In fact, I end the book with a series of unanswered questions about Acharya. Particularly his memoirs covering a much longer period than those already published, as well as a book he wrote, called Mutualism, which I have not been able to find either.

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at meher.marfatia@mid-day.com/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!