A journalist’s book, which comes a little ahead of Goa’s 2022 Assembly elections, busts myths about the state that has a chequered history of defections and coalition calculations

A file picture of voters waiting in line to cast their ballots at a polling station in Davorlim village near Margao, during the 2012 Assembly elections. Pic/Getty Images

![]() In the year 2012, former Gujarat CM Narendra Modi was BJP’s greatest asset. Being seen as the only leader who could catapult the party to the national stage, he was the most sought-after speaker at BJP rallies across Indian states, except Goa. Late Goa CM Manohar Parrikar, who praised Modi’s magnetic pull, consciously avoided the leader, because he felt that the Hindutva rhetoric would not work well on Goa’s soil; Modi’s speeches would estrange the 25 per cent Christian voters, on whose shoulders the BJP rested. The Modi vibe wasn’t perceived suitable for Goa’s “thinking voter”.

In the year 2012, former Gujarat CM Narendra Modi was BJP’s greatest asset. Being seen as the only leader who could catapult the party to the national stage, he was the most sought-after speaker at BJP rallies across Indian states, except Goa. Late Goa CM Manohar Parrikar, who praised Modi’s magnetic pull, consciously avoided the leader, because he felt that the Hindutva rhetoric would not work well on Goa’s soil; Modi’s speeches would estrange the 25 per cent Christian voters, on whose shoulders the BJP rested. The Modi vibe wasn’t perceived suitable for Goa’s “thinking voter”.

ADVERTISEMENT

Parrikar, candid and accessible as ever, shared his insight on Goa’s DNA, over a cup of tea with senior editor Sandesh Prabhudesai, then leading Goa’s Prudent TV channel. Prabhudesai recalls off-the-record observations, which he hasn’t included in the first volume of his forthcoming book Ajeeb Goa’s Gajab Politics, to be published by Goanews.com early next month.

Editor Sandesh Prabhudesai stresses that Goa is the only state, which experienced a referendum in Independent India, which offered the opportunity to merge with Maharashtra. The people of Goa chose, way back in 1967, their separate cultural Konkani identity, even if that meant reduced clout in the corridors of power and resultant minuscule central government funds

Editor Sandesh Prabhudesai stresses that Goa is the only state, which experienced a referendum in Independent India, which offered the opportunity to merge with Maharashtra. The people of Goa chose, way back in 1967, their separate cultural Konkani identity, even if that meant reduced clout in the corridors of power and resultant minuscule central government funds

“Three decades of political journalism has accrued tons of anecdotes centering around multi-hued politicians, not just Parrikar. I treasure these asides, jokes, and reflective moments over tapri chai,” Prabhudesai told this columnist.

Prabhudesai, 61, is a classic case of the “insider” writer—born and raised in Goa, he was devoted to street theatre and student activism as a teenager, and has invested the last 33 years in journalism. He is an award-winning Konkani-English-Marathi editor, and has been BBC’s Goa correspondent since 2000. He led the Right to Information movement in Goa in 1997 in the role of the General Secretary of the Goa Union of Journalists. His book is therefore, an oblique critical and introspective look at Goa’s psyche, political-social choices and above all its rebellious streak, “which hasn’t been put to productive use”. He feels the Goans aren’t sufficiently cognisant of their own legacy. They are not mindful of the fact that Goa is the only state (Union Territory up to 1987), which experienced a referendum in Independent India. Called the Goa Opinion Poll for political reasons, this referendum offered the opportunity to merge with Maharashtra. The people of Goa chose, way back in 1967, their separate cultural Konkani identity, even if that meant reduced clout in the corridors of power and resultant minuscule central government funds. Prabhudesai’s book awakens the “niz Goenkar” to live up to their fierce independent streak and elect well-meaning legislators in the crucial assembly elections in February 2022.

Late Goa CM Manohar Parrikar, who praised Narendra Modi’s magnetic pull, had initially avoided inviting the leader to the state. Parrikar wasn’t sure if Modi rhetoric was suitable for Goa’s “thinking voter,” says Prabhudesai. Pic/AFP

Late Goa CM Manohar Parrikar, who praised Narendra Modi’s magnetic pull, had initially avoided inviting the leader to the state. Parrikar wasn’t sure if Modi rhetoric was suitable for Goa’s “thinking voter,” says Prabhudesai. Pic/AFP

Ajeeb Goa’s Gajab Politics charts Goa’s trajectory in the context of its political uniqueness, its peculiar odd-ball character that cannot be easily co-opted in the national mainstream. India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru once said: “Ajeeb hain ye Goa ke log”. He was referring to the strange demand of sizeable Goans, who wanted to be part of Marathi-speaking Maharashtra. This pro-merger group represented the peasantry which didn’t particularly speak Marathi. The upper caste Goan Brahmins, who were fluent in Marathi claimed Konkani as their mother tongue. But, Goa’s major temples, controlled by Brahmins, don’t use Konkani signage. Temple trusts prefer Marathi and English over Konkani. But, the trust owners are traditionally sentimental about the Konkani ethos. These paradoxes puzzled Nehru in understanding the pro and anti-merger factions.

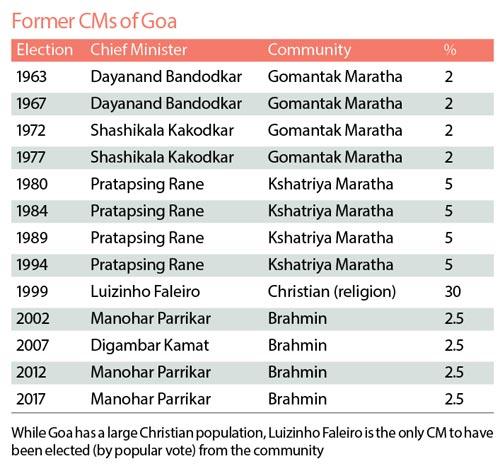

As Ajeeb Goa’s Gajab Politics recounts these entertaining episodes, the author underlines the state’s radical mandates since its inception. For instance, the first election after Goa’s liberation from the Portuguese witnessed the victorious rise of the Maharashtrawadi Gomantak Party. The anti-merger United Goans Party was pushed to the opposition benches. The Congress, which had no firm stand on language and the merger, was wiped out. In 1967, the first assembly was dissolved midway and people, who supported MGP, cast a vote against the merger in the referendum. But they soon voted MGP to power in the assembly elections; the first CM Bhausaheb Bandodkar was firmly back in the saddle. Interestingly, Goa’s CMs have not hailed from communities with large vote banks; also, it has (by popular vote) elected only one Christian CM, Luzinho Faleiro in 1999.

Prabhudesai says Goa’s voter behaviour cannot be taken for granted; neither can religion, caste or language compel the voter to cast his or her vote along parochial lines. The book, in fact, prides on examples of communities/castes, which didn’t vote “for their own likes”, be it the Bhandaris or the Adivasis or the Christians. Take, for instance, Sudin Dhavalikar, a five-term member of the Goa Legislative Assembly representing the Marcaim constituency in North Goa. He is a Brahmin by caste. Marcaim is dominated by the Bhandaris; it is a cluster, which in the past has voted for freedom fighter Vasant Vellingkar (Gomantak Maratha), but it hasn’t consciously chosen a Bhandari for the sake of caste unity. Similarly, the Mandrem constituency with a dominant Bhandari presence has elected Marathas and even a Christian candidate, but not “amcho jaatintlo”. After AAP’s entry in Goa’s politics, the unity of Bhandari Aadmi has been a hot topic. But Prabhudesai recalls the past rejection of KB Naik, an influential Bhandari leader.

Goa’s people, says the author, set aside religion while voting, a fact that is inspiring for the rest of India where “religious unity” has played havoc in voting preferences. “It is not that they articulate their choice as ‘secular’, but there is a tradition of assessing the candidate and the political outfit. For instance, in 1972, Christian-dominated Benaulim was won by Vasudev Sarmalkar on the UGP ticket; he defeated former MLA Elu Miranda. But after two years, a Christian was chosen in the bye-election, this time on the MGP ticket. Since MGP was perceived as a nativist party of the Hindus, its acceptance in Benaulim was surprising.”

Two more examples in the book are inspiring. Hindu-dominated Mormugao elected (five times) a man of letters and former judge, Muslim by religion, Shaikh Hassan Haroon. When Haroon first stood for election on a Congress ticket in 1977, Mormugao’s Muslim population was barely nine per cent. Today, it has grown to 16 per cent of the total 21,000 electors; their voting is not governed by religious considerations. In Curchorem, again a Hindu-dominated constituency, Muslim legislator Abdul Razak and Christian candidate Domnic Fernandes, both Congressmen, have had fruitful stints.

The first volume of Prabhudesai’s book races against a deadline—the upcoming announcement of the February 2022 Assembly elections. But, the ensuing volumes will dive deeper in larger cultural themes as well as the local politics surrounding land ownership. It will go into the historical reasons for the current behaviour of Goan voters and their elected representatives. Why are Goa’s CMs toppled by intriguing defectors? How do defectors face their voters in a one-on-one setting, especially since Goa’s 40 assembly segments hold 18,000 to 25,000 (intimately known to the candidate) people? Is the texture of electioneering at the municipal level messier? It is also a matter of academic study that while a major national party, Congress, has lost its clout in Goa’s politics, its replacement, the BJP, presents a worse shade.

Readers are interested in these aspects of a crucial small-sized, but strategically-positioned coastline state. Goa has an impressive literacy rate, it has a great tradition in public service journalism, it shines as a tourist heaven, it excels in the performing and visual arts, its green countryside holds bio-diverse riches. And yet, it is remembered on primetime television for a fractious bickering political leadership. Goa’s migrant resident, with no historic connect, is rumoured to be bought at a rate of Rs 4,000 per vote. Defections of Goa’s legislators forever provide fodder for the WhatsApp joke club. This book tells Goans to do away with these gajab factors.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar @mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!