Everyone thought the matter had been forgotten, but then Rushdie was brutally attacked. Here feeling hurt and taking offence was the problem

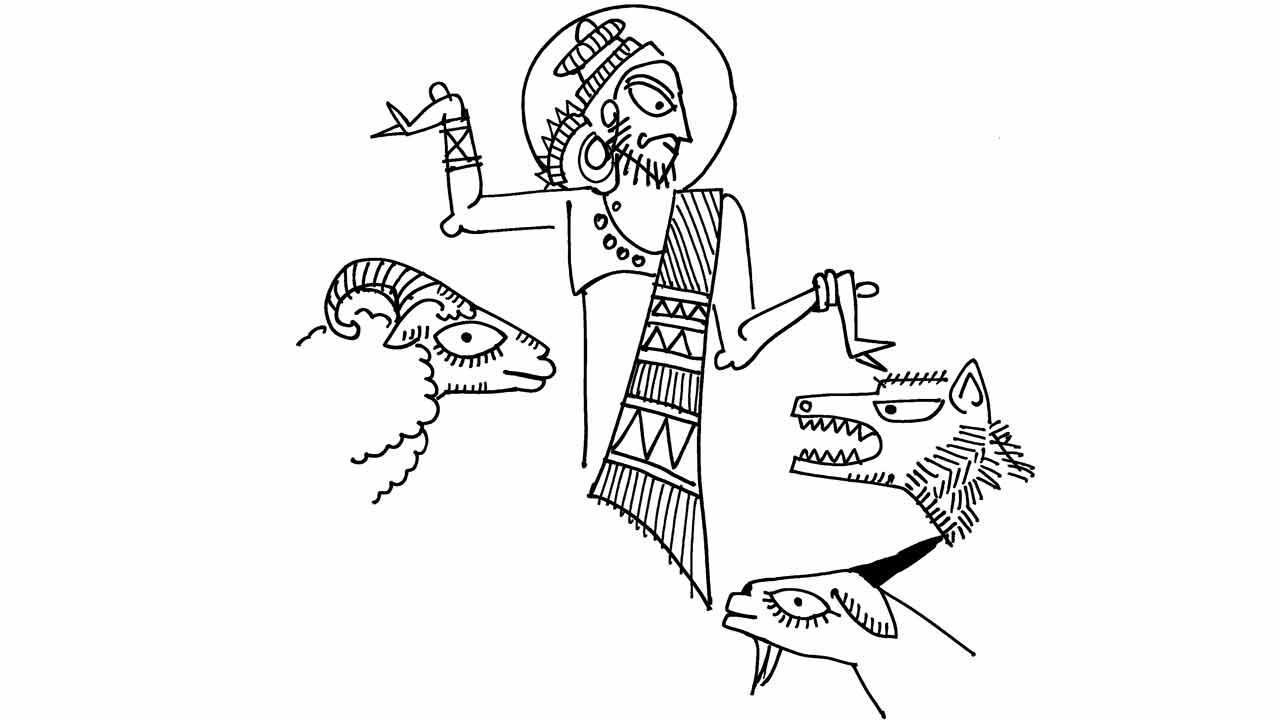

Illustration/Devdutt Pattanaik

What is the opposite of freedom of speech? It is the right to get offended. Recently, Nupur Sharma commented about Prophet Muhammad’s marriage on national television. She stated in a debate and it was not meant to flatter. The Arab elite, otherwise mute spectators to global Muslim misery, took exception. The Indian government had to calm frayed nerves. Here, speech was the problem.

What is the opposite of freedom of speech? It is the right to get offended. Recently, Nupur Sharma commented about Prophet Muhammad’s marriage on national television. She stated in a debate and it was not meant to flatter. The Arab elite, otherwise mute spectators to global Muslim misery, took exception. The Indian government had to calm frayed nerves. Here, speech was the problem.

ADVERTISEMENT

Long ago, Salman Rushdie wrote a work of fiction called Satanic Verses inspired by a story of the Prophet Muhammad. It offended some Muslims who demanded his death. A fatwa was issued, and Rushdie went into hiding for years. Everyone thought the matter had been forgotten, but then Rushdie was brutally attacked. Here feeling hurt and taking offence was the problem.

If authors have freedom of speech, shouldn’t politicians? Why should only one religious group have a right to outrage? A good lawyer can turn any villain into a victim, turn any act of violence into an act of justice, portray any terrorist as a martyr, transform all Opposition leaders into anti-nationals. Justice is today a function of language, wealth and power. This draws attention to the problem of truth. Should bitter truths, or sour fictions, be silenced as they hurt?

In his book, Salman Rushdie chooses to identify Bollywood mythological films as “theologica” films. The choice of words by a master wordsmith reveals a deep tension. In colonial times, monotheism (Christianity and Islam) had theology while polytheism (Hinduism) had mythology. This irritated Hindu intellectuals, who till date, insist Hinduism is actually monotheism and so its mythology is also theology. By using the word theology for Hindu stories in his work of fiction, Salman Rushdie was being culturally sensitive towards oversensitive Hindus, in a book that ironically upset oversensitive Muslims.

Myths are neither facts, nor fictions. They are beliefs, cultural ideas, subjective truths, true for insiders, false for outsiders. God is myth; so is law. There is no universal law: Sharia law is supposed to be true for Muslims, Manu’s law is supposed to be true for Hindus, and Constitutional Law, written by lawyers, is supposed to be true for all Indian citizens. They all see rape and murder is crime—but differ on what defines it, how it can be proven, and how much punishment it deserves. In modern societies that subscribes to the myth of justice and equality, rich people cannot get away by paying honour and blood money as compensation for rape and murder. But rich people can hire the best lawyers in town.

In nature, there is neither rape nor murder, because there is no concept of consent or boundaries. We keep saying ‘natural laws’—but there are no lawyers or police or judges to enforce laws in the wild. In the jungle, there are no victims, villains or heroes; might is right; the big eat the small. Nature is so meritocratic that it lacks morality.

Morality and ethics are human constructs designed to make us care for the less meritocratic, and the less privileged. It propagates the myth of victims, villains and heroes. To win in a debate, you must therefore position yourself as a victim. Victims are allowed to be oversensitive, to demonstrate inequality. Victims are allowed to abuse, to fight injustice. This is how modern mythology of justice and equality is performed through victimhood.

The author writes and lectures on the relevance of mythology in modern times. Reach him at devdutt.pattanaik@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!