Can you knit a sculpture, embroider a painting? Two artists showing in Mumbai are looking beyond paint-brush to explore method and material typically associated with fashion

Master zardozi artisans at Kalhath Institute, Lucknow, embroider an artwork by T Venkanna as part of an artist residency designed to promote innovations in art and craft. Pic Courtesy/Gallery Maskara

The thread lends itself to many metaphors. We think of our lives—and of stories—as spun, stretched or interwoven with that of others into the fabric of a community, culture, mythology or nature. And it is this opportunity that artists T Venkanna and Smriti Dixit are using to introduce a gamut of themes from sexual freedom to feminine power and the link between art and sustainability. Showing at Gallery Maskara and Art Musings respectively, they make for a worthy multidisciplinary story emerging from the recently concluded Mumbai Gallery Weekend.

The thread becomes a medium to discuss longing, pleasure and frustration in Baroda artist Venkanna’s As I Am embroidered paintings. Co-created with with master zardozi artisans from Kalhath Institute in Lucknow, the exhibition is a revelation and a delight as the needle replaces the paintbrush, while “blurring the boundary between art and craft, artist and artisan”, as gallerist-curator Abhay Maskara puts it.

Abhay Maskara

Abhay Maskara

In Savage Flowers, Dixit captures the natural flow and hewing of tactile possibilities. She gives knitting, hallowed for its inclusive, domestic and meditative qualities, a rhetorical punch both in material and persona by substituting wool with industrial plastic tag fasteners. Homemakers from her Kandivali neighbourhood join her in the needlework sessions.

The work of both artists belongs to our time, except that they look back as much as they leap into the future, suggesting that craft today is part of a broader visual language.

T Venkanna ///

Method: Embroidery

Material: Thread, sequins, beads

Dentata, 2021, is part of T Venkanna’s As I Am series of embroidered paintings

Dentata, 2021, is part of T Venkanna’s As I Am series of embroidered paintings

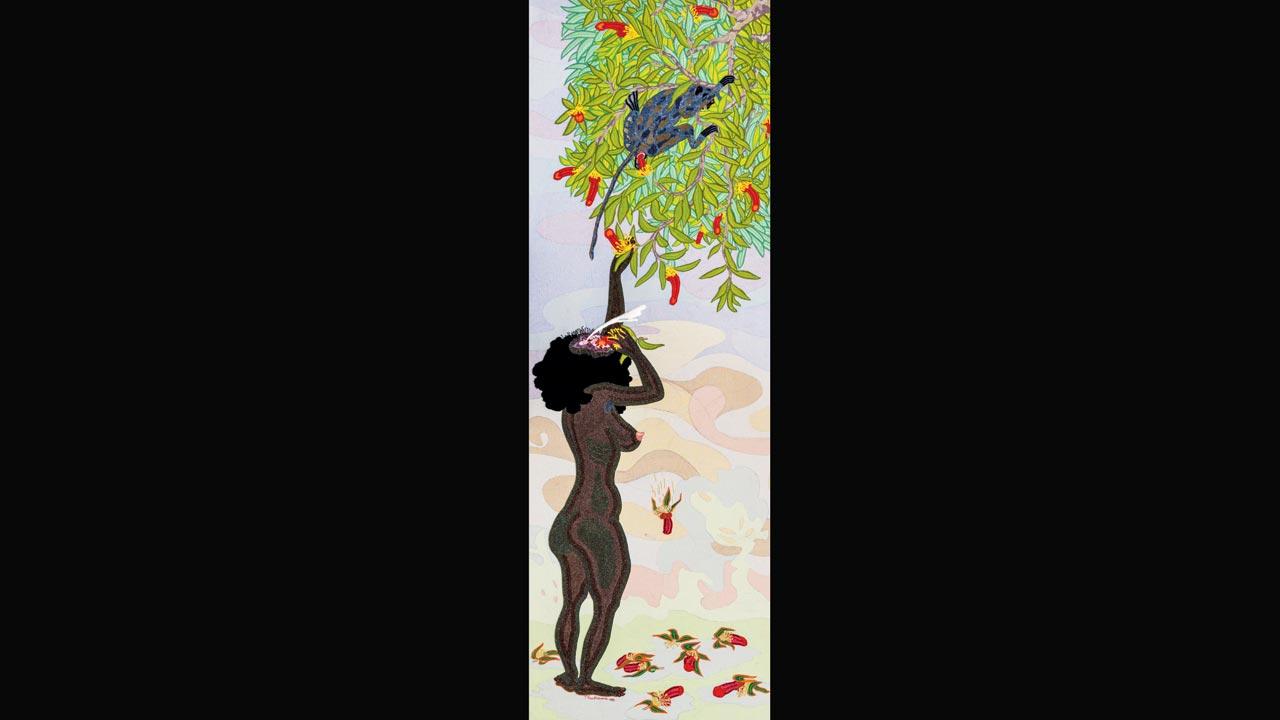

The art of T Venkanna is impossible to look away from, and the longer you look, the more wild and imaginative it appears. A woman with flat black hair stands butt-naked, her nipple curled with pleasure. She reaches out to a branch to pick a phallus-looking fruit, the other arm gesturing as if she is feeding her mind that’s split open. A mammal crouched on the branch mimics her action, or is it the other way around? The work titled Dentata, 2021, is part of Venkanna’s As I Am solo show (on view till March 12).

Grilles and grids of woven colour outline her curves, flesh and muscle—textures that were not easy to achieve, adds Venkanna, 41, who first drew her on a canvas, before envisioning a matrix of threads and sequins that would be hand embroidered by zardozi craftsmen in Lucknow. The merging of two mediums is gorgeous in detail, shimmering in surface and glows against the dimly lit gallery space. This collaboration is a product of persistence and persuasion. “The embroidery artisans were apprehensive about the forms and subject,” Venkanna smiles. “They were trained in making traditional motifs of birds and flowers on garments like ghagras. But once they understood my work, they were not only on board but also made suggestions on textures and colour.”

Pic Courtesy/Fabien Charuau

Pic Courtesy/Fabien Charuau

Another piece called Lovers is laid horizontally like a tabletop, as if to suggest that it’s still on the loom at Kalhath Institute. The Lovers are hermaphrodites, joyfully engaged with each other, cocking a snook at the puritanical society. “Art, like sex, is human impulse. The artist wants you to think about how we are divorced from our own bodies, its pleasures,” says Maskara.

Venkanna agrees, placing sexual exuberance over social politeness. “An individual achieves pleasure out of this simple act of day-dreaming.” And this desire roams free, normalised in his world where domesticated cats, dogs and roosters have as much place as mythical eagles. “There is no one defined story,” explains Maskara. “The mind has to take a backseat and let imagination lead [when you view his work]. [For some] it’s the melody of colours and intensity of embroidery that speaks to them. For others, it’s about [being one with] nature, and then about Indian history and mythology.”

Venkanna lets it all flow uninterrupted through line drawings on the canvas before the colours rush in, with karigars working their needles, as he watches them “paint” his vision. Does he feel a loss of control? “Material and method is secondary, what I want to convey is important.”

Smriti Dixit ///

Method: Knitting, weaving, dyeing

Material: Cotton, string, nylon, plastic

Smriti Dixit’s Declaration is shaped like the uterus, woven from fabric and string

Smriti Dixit’s Declaration is shaped like the uterus, woven from fabric and string

A bulgy mass of vermilion cotton and algae nylon with lateral tentacles and a ‘tail’ sits on the floor of the art gallery like a sea creature at the bottom of the ocean. Stunned, we squat for a closer look. “You can touch it,” gestures gallerist Sangeeta Raghavan. “Smriti’s [Dixit] work is tactile, so we invite everyone to feel it.”

Part of Dixit’s solo exhibition, Savage Flowers (on view till March 15) curated by Nancy Adajania, the Declaration is a textile sculpture that places the female uterus as a point of inquiry, even as it challenges patriarchal taboos. The coarse cotton in the colour of menstrual red, and its form stings like the the pain felt deeply like from a wound dragged too far out of ghoulish realism. This textural interpretation of the female anatomy is made up of nothing but fabric held together by threads that mesh it like pulsating blood vessels, as the ovaries are suspended on each end in the shapes of tiny cocoons of fabric. It’s marvelous, scary and provocative all at once.

Sangeeta Raghavan

Sangeeta Raghavan

Dixit, 50, says the controversial Sabarimala case in which women of menstruating age were banned from entering the temple was the starting point. The Kamakhya temple in Assam is dedicated to the Bleeding Goddess, her mythical womb enshrined in the sanctum sanctorum. But menstruating women are denied entry into temples. “Everything that’s immensely powerful is curtailed. It’s the same with Shakti, the woman—the only one with the power to create another,” she thinks.

The entrenched inequities are as primal to her work as the unconventional methodology. Declaration has no armature inside the cotton. The dense, solid Yoni (vagina), knitted from plastic tag fasteners spray-painted black, is not hollow either. Every piece speaks of long hours and labour, something Dixit says women are accustomed to.

As a young girl in Bhopal, Dixit was drawn to knitting. “My mother handed me three bales of wool, and that’s all I would get. I’d knit by day, and undo it at night, so I could make something new from the same material the next morning.” For some, this amounts to futility. For Dixit, it’s meditative and magical. “Creating something new from old; doing, deconstructing and redoing, isn’t that what sustainability is about?”

Working from her Kandivali studio, Dixit uses what the environment throws up, and some, she buys; plastic tags in bulk from Crawford Market and fabric from Malad’s Natraj Market. Shredded into long, ribbon-like yarn, she dyes them selectively before knitting them into sculptures, all manually, her arm becoming an extension of the work.

The Longing sculpture is a group of perforated screens that hang from the gallery’s rafters—surreal waves of dyed maroon, orange with specks of blue flowers and butterflies—that you can walk through. “Are these trees or totem poles?” Adajania wonders in the show’s catalogue. They can be anything you want them to be. Like the artist herself. In 2017, Dixit showcased a line of handcrafted jewellery at Lakmé Fashion Week. She joins the growing chorus of creative minds asking: who gets to make art?

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!